"Princess Caraboo" was actually Mary Baker Willcocks, an English cobbler's daughter who fooled an entire town near Bristol, England into believing she was royalty from the Pacific island of "Javasu."

Edward Bird/Wikimedia CommonsThe artist Edward Bird painted Princess Caraboo’s portrait in 1817.

On the Thursday before Easter in 1817, a strangely dressed woman walked into Almondsbury, a village eight miles north of Bristol. Carrying no more than soap and a few coins, the mysterious woman began knocking on doors, calling herself Princess Caraboo. And when villagers answered, she spoke a language no one could understand.

But was the stranger a beggar? Or an Indonesian princess? The pale-skinned woman eventually explained – through a Portuguese translator – that she was Indonesian royalty who had been captured by pirates. She only escaped by jumping overboard and washing ashore near Bristol.

The mystery of Princess Caraboo captivated the community. But was the woman an imposter?

Who Was Princess Caraboo?

The villagers of Almondsbury had no idea what to make of the stranger wearing a shawl and turban. The woman spoke in a tongue none in Gloucestershire could understand. Only two words stood out: “Caraboo,” the word she used while pointing to herself, and “nanas,” the Indonesian word for pineapple.

Baffled by the woman, the village cobbler took her to Mr. Hill’s house. As Overseer of the Poor, Mr. Hill hauled vagrants before the court. But was the woman a beggar? Hill carted her off to the Town Clerk, Mr. Worrall, who happened to have a Greek butler. Yet not even the butler recognized the stranger’s language.

Alfred Gomersal Vickers/National TrustA 19th-century painting of people meeting on a country road by Alfred Gomersal Vickers.

Almondsbury was clearly not equipped for a mystery of this sort. So they sent the woman to Bristol, where the mayor examined her. Yet none could make sense of this woman who spoke an unknown tongue.

Until Manuel Eynesso, a Portuguese sailor, entered the conversation. Eynesso said he recognized the woman’s language: she spoke Indonesian. And he promised to translate her tale of woe for Bristol.

The Portuguese Sailor Who Could Understand Princess Caraboo

According to Manuel Eynesso, the woman was not a vagrant or a beggar. Instead, she was Princess Caraboo from Javasu. Captured by pirates and held on their ship, the woman had barely escaped with her life.

Was the story true? It seemed just plausible enough to convince Bristol.

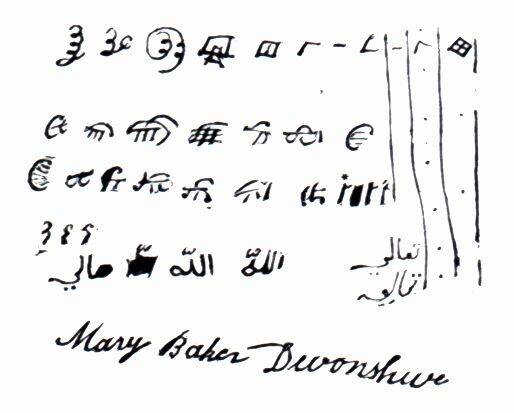

Mr. Worrall encouraged the stranger to record her exotic script. He sent off the papers to Oxford for the scholars to analyze.

Mary Baker/Wikimedia CommonsThe princess wrote in a strange script, which the villagers sent off to Oxford for analysis.

Eynesso became the princess’s informal translator. And Princess Caraboo became the sensation of southwest England.

For more than two months, the English treated the princess like a foreign dignitary. She performed Indonesian dances for the magistrates, prayed to a god named “Allah-Talla,” and sat for a portrait. The city of Bath even threw her a ball.

Princess Caraboo also scandalized the English by swimming nude in a lake.

The princess certainly had unusual habits. She only ate vegetables and drank nothing but tea. She could shoot an arrow and fenced with a sword tip dipped in poison.

Scholars traveled to meet with Princess Caraboo. One even confirmed her language was, in fact, Indonesian. Reporters flocked to interview the foreign dignitary, printing her story in the paper. And one of those stories eventually exposed the entire hoax.

Mary Baker, The Woman Behind The Princess

In June 1817, Mrs. Neale, a landlady, opened her newspaper and read about Princess Caraboo. Right away, Neale knew the princess was a liar and hoaxer.

Neale had rented a room to the woman months earlier – around the time she was supposedly in the hold of a pirate ship. The landlady remembered the strange girl, who loved to wear a turban and speak in an invented tongue. And the fraud’s real name was Mary Baker.

The story quickly unraveled. Mrs. Neale confronted Princess Caraboo, who suddenly spoke perfect English. She confessed to inventing the entire story. The Portuguese sailor had been her accomplice.

A. Topping/Houghton LibraryAt balls and social events, ladies fawned over the Indonesian royal.

When Oxford scholars examined Caraboo’s written script, they deemed it “humbug language.” Others pointed out that there was no island called Javasu.

An Exeter newspaper published the tale of Princess Caraboo:

“The wonderful Female, who has outwitted the Doctor, puzzled the learned, and astonished the multitude, turns out to be a vile impostor, a vagrant wanderer, and daughter of a poor cottager.”

Another paper wrote an ode to the fraudster: “I admir’d thy Caraboo./Such self-possession at command,/The bye-play great—th’ illusion grand:/In truth—’twas everything but True.”

Mary Baker made up the tale of Princess Caraboo. In reality, she was the daughter of a cobbler.

But, surprisingly, the villagers did not turn on the unmasked princess. Instead, they helped pay for the destitute woman to sail to Philadelphia. The Americans were excited to meet Mary Baker, who told tales of her adventures.

One story even claimed Baker met Napoleon when a storm blew her ship off course to St. Helena, where the former emperor lived in exile.

In 1824, Baker returned to England. She tried to launch an acting career, which fizzled. So she eventually married and launched a new career selling leeches to a local hospital.

Mary Baker carried on her career as an “importer of leeches” with “much judgment and nobility,” according to one newspaper.

Why Did Mary Baker Turn Herself Into ‘Princess Caraboo’?

In the early 19th century, Bristol welcomed ships from around the world. It was easy to imagine that pirates might sail past England’s coast. And many fell for the tale of a beautiful princess far from home.

But why did Mary Baker invent such a far-fetched tale? And did she truly think she could hide the truth? Although she lived for decades after the Princess Caraboo hoax, the cobbler’s daughter never revealed her motives.

Nathan Cooper Branwhite/Wikimedia CommonsThe mysterious Princess Caraboo became an instant sensation in Bristol.

It’s easy to imagine Mary Baker walking into a less trusting village and finding a very different reaction. A harsher magistrate might have sent the wanderer to prison or a work camp. Less kind townspeople might have mistreated the vulnerable woman. And Mary Baker would never have attended a ball or visited America.

In the end, even though Princess Caraboo was an imposter, she put Almondsbury on the map. The villagers proved that they took care of strangers – even after their hoaxes were exposed.

Princess Caraboo pulled off her hoax for a time. Next, read about other famous hoaxes and then learn about the Cardiff Giant, a 19th-century hoax that fooled thousands.