With U.S. crime down yet prisoners up, and private prisons raking in billions off their labor, it's becoming increasingly clear that American slavery has returned with a new name.

Mark Wilson / Getty Images

OVER THE PAST 25 YEARS, something wonderful has happened.

The United States’ crime rate has sharply decreased, careening consistently downward at an unprecedented rate.

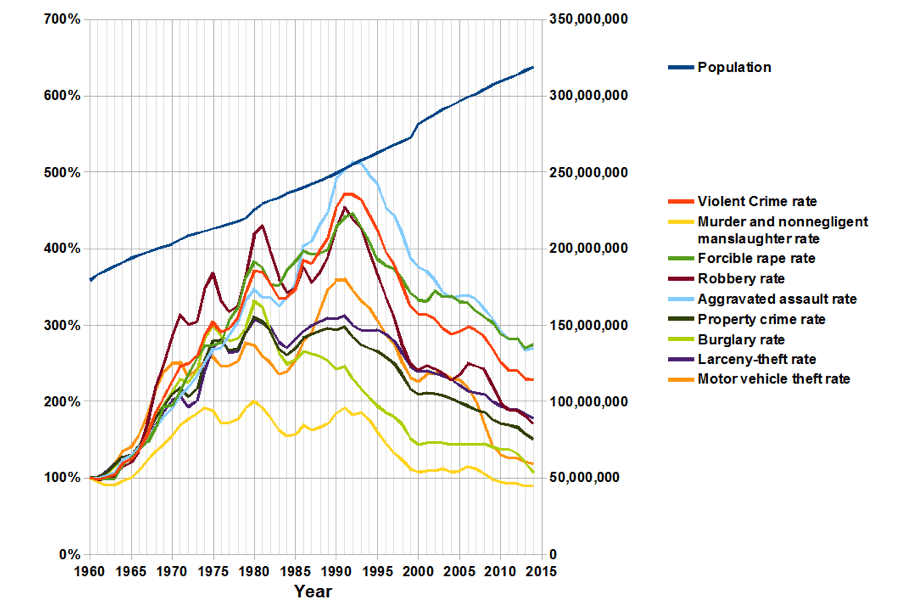

Murder, rape, robbery, burglary, you name it — according to both current and historical data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, violent and property crime have both shrunk to about half of their early 1990s highs, and now sit at 50-year lows with no signs of picking back up.

While 2015 was dubbed “the year of mass shootings” in the U.S. — and, tragically, with good reason — few of us seem to realize that the U.S. murder rate is less than half of what it was in 1993, that it has declined every year since 2006, and that it is now the lowest it has ever been as far back as the F.B.I.’s publicly available records go (1960).

Graph tracking the U.S. crime rate across several parameters, compared with population growth from 1960 to the present. Note the sharp, across-the-board decreases starting in the early 1990s. Source: F.B.I. Image: Wikimedia Commons

So why doesn’t the state of crime in the U.S. seem all that wonderful?

Maybe it is because of the preponderance of appalling, headline-grabbing mass shootings. Maybe it’s because crime is an awful thing and so we think we could always do better. Maybe it’s because the U.S. homicide rate actually is, according to United Nations statistics, rather high when compared to the rates in other developed nations.

Or maybe it’s because even though the U.S. crime rate has dwindled, the end of the line for all this crime — the U.S. prison population — is somehow still booming.

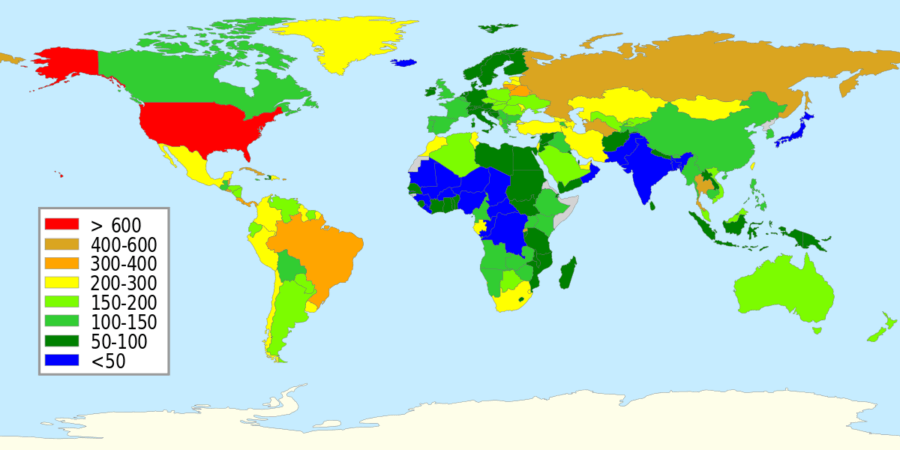

Source: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Image: Wikimedia Commons

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, the number of incarcerated people in the U.S., as of the last report (2014), was 2,224,400. Considering that the U.S. population is about 321 million, that means that one in every 145 Americans is incarcerated. But if that number seems low, it’s only because Americans have become inured to the abysmal state of our criminal justice and penal systems.

Map revealing incarceration rates per 100,000 people around the world. Source: World Prison Brief. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Another way to look at that one-in-every-145 figure is to say that 716 out of every 100,000 Americans is incarcerated. For comparison’s sake, more than half of the world’s countries have rates below 150 per 100,000. The average across Europe? 133.5.

Framed differently — and popularly so in presidential primary stump speeches — while the United States has less than five percent of the world’s population, it has almost 25 percent of the world’s prison population.

Improvised housing at California’s Mule Creek State Prison, one of the most crowded prisons in one of the states most faced with crisis with a prison population that is simply too large (2007). Photo: Justin Sullivan / Getty Images

And even as the U.S. crime rate has dropped and dropped, the country’s prison population has soared. The symmetry is almost comically perfect: Since its peak in 1991, the U.S. crime rate has been cut almost exactly in half. Yet over that same time frame, the country’s prison population has almost exactly doubled — and since 1980, it’s quadrupled.

Why?

The War On Drugs

A Colombian police officer stands among confiscated drugs in Cali on March 26, 2013. Photo: LUIS ROBAYO / AFP / Getty Images

THE VERY FIRST ANSWER you likely thought of has indeed become tragically obvious: The War on Drugs.

In the lead up to last month’s historic U.N. summit on overhauling global drug policy, the media, academics, and elected officials released a tide of damning statements on the decades-long failure of the U.S. War on Drugs.

That failure is undeniable.

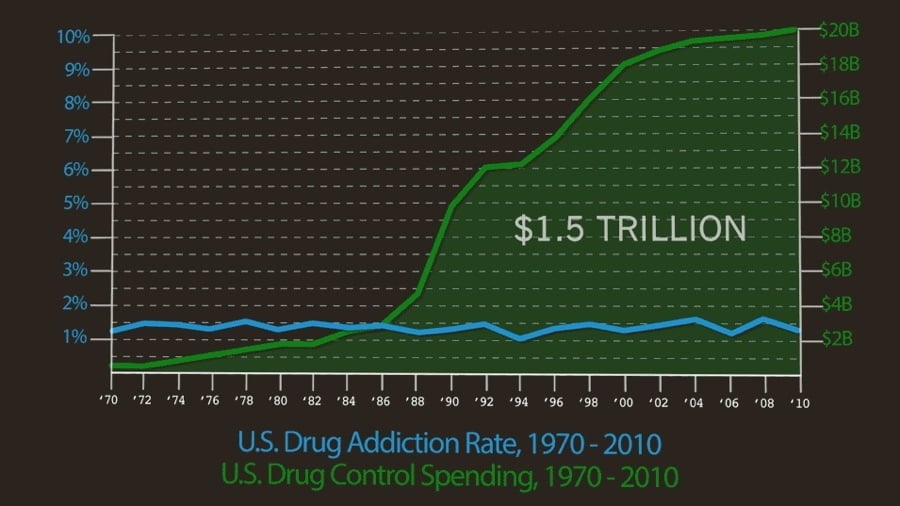

According to the White House’s recently released National Drug Control Budget for 2017, the country’s planned spending on both treatment and law enforcement related to illegal drugs next year will reach $31.1 billion, a number that has risen every year for the last decade.

More than $15 billion of that budget will go toward law enforcement (if there’s one silver lining here it’s that the country has been funneling a lot more money into the treatment side of the equation in recent years, with that side of the budget doubling since just 2009).

Of course, those are just the planned expenses, not the ones that will actually result from all the drug-related incidents that occur throughout the year — and which you can’t exactly plan for.

When the year is over and all the country’s drug-related expenses are tallied up, the number will likely be nearer $193 billion (the figure from the last U.S. Department of Justice report on the matter made available — tellingly, from 2007).

And for all that money, all that effort, all those resources, both drug use and drug crime in the U.S. have risen in recent decades.

Sources: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, International Centre for Science in Drug Policy. Image: The Wire

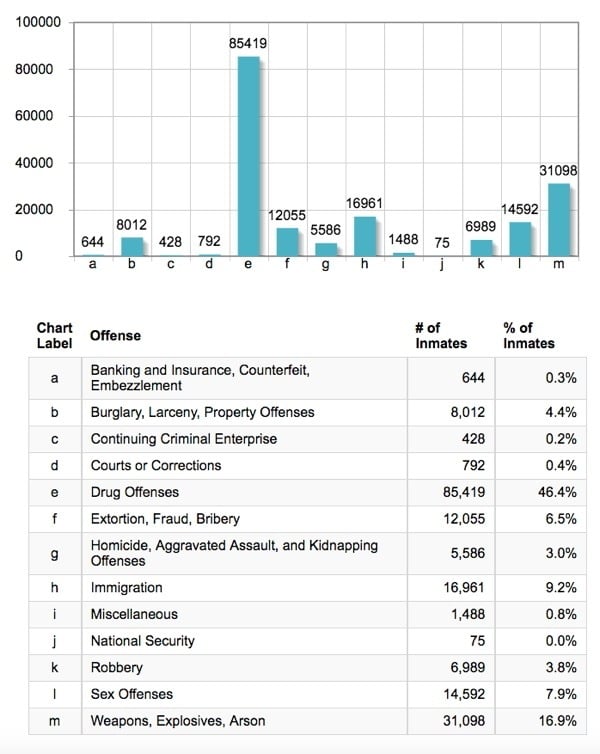

Thus, it’s no surprise that drug offenders represent a wildly disproportionate percentage of the total U.S. prison population and help account for its boom.

The breakdown of inmates currently in U.S. federal prisons by crime, as of March 2016. Source: U.S. Federal Bureau of Prisons

But even still, the War on Drugs does not fully explain why the U.S. prison population is soaring as crime rates are falling. While that war and its failure get plenty of ink, the other, perhaps even more sinister reason why U.S. prisons are so well-stocked hardly makes headlines at all.

Prison For Profit

The Adelanto Detention Facility in Adelanto, California, owned by The GEO Group, the highest-grossing private prisons corporation in the United States today. Photo: John Moore / Getty Images

AS OF 2014, more than eight percent of U.S. prisoners and 62 percent of immigrant detainees are held in privately-owned prisons.

These private prisons are run by corporations, and like all other corporations, they are beholden to investors and are in the business of making profits. And in the U.S., the for-profit prison industry is booming.

Image Source: Prison Policy Initiative

In 1983 and 1984, two private corrections corporations formed, one after the other. First, in Tennessee, there was the Corrections Corporation of America. Then, in Florida, The GEO Group.

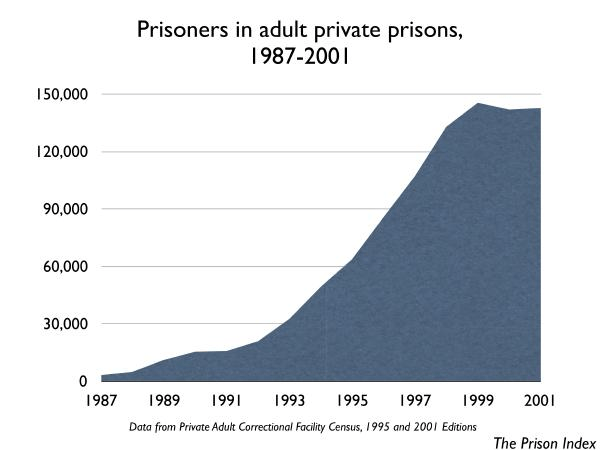

Both started small and grew slowly at first, but eventually, business took off — unbelievably so. Between 1990 and 2009, the number of inmates in private prisons increased by an astonishing 1600 percent.

CCA and GEO each spend well over $1 million a year contributing to political campaigns (in addition to untold lobbying costs likely in the tens of millions) in order to make sure that both the laws being written and the government contracts being handed down keep their private prisons stocked with inmates.

Cramped, improvised living quarters at California’s Mule Creek State Prison. Over 17,000 prisoners in California live in this kind of “non-traditional” housing. Photo: Justin Sullivan / Getty Images

It’s working. And with so many prisoners, profits have shot sky high. CCA revenue hit a whopping $1.79 billion in 2015, up from the year before, while GEO revenue hit an even higher $1.84 billion, likewise an improvement over their previous year.

Now, how exactly do these corporations turn prisoners into well over $3 billion worth of revenue every year?

It’s not quite slavery, but it’s close.

MIKE SIMONS / AFP / Getty Images

Largely by working with Federal Prisons Industries (a government-owned corporation, also known as UNICOR, that serves as a contractor for prison labor), CCA and GEO put prisoners to work (in factories, agriculture, textiles, and more), pay them next to nothing, and reap the rewards of the inmates’ labor.

While, unsurprisingly, statistics on prisoner wages aren’t exactly easy to come by, the often cited figure is between $0.23 and $1.15 per hour. The total wages paid — to every single laborer combined — as reported by UNICOR for 2015 were just $33,538. Total revenue? $558 million (up almost $90 million from the year before).

Daniel Lobo / Flickr

With labor this cheap in the marketplace, plenty of companies (like American Apparel) have been underbid for lucrative contracts, while plenty of other companies (like Whole Foods) have contracted with UNICOR and come under fire for exploiting what is virtually slave labor.

And comparing the CCA/GEO/UNICOR prison-industrial complex to slavery becomes all the more chilling when we remember that the booming U.S. prison population is, to an unbelievably disproportionate degree, African-American.

Private Prisons: The New Slavery

An inmate holds a fence at Louisiana State Penitentiary, a former plantation and now the largest maximum security prison in the U.S. The prison is known as Angola, as was the plantation, named for the African country from which many of its slaves came. Photo: Mario Tama / Getty Images

EVEN THOUGH AFRICAN-AMERICANS make up just 13 percent of the U.S. population, African-American males make up 37 percent of the male U.S. prison population.

Put another way, 2.7 percent of African-American males were sentenced to more than one year in a state or federal prison at the end of 2014. The figure for white males was just 0.5 percent, making African-Americans five times more likely to be behind bars.

And the numbers are particularly lopsided when it comes to drug offenses. Although five times more whites than African-Americans are using drugs, African-Americans are imprisoned for drug offenses at ten times the rate that whites are.

Given the recently resurfaced interview with a top aide to President Nixon explicitly claiming that the War on Drugs was actually a war, in part, on African-Americans, it’s not hard to see how prisons, private prisons in particular, might be just the newest system for forcibly funneling African-Americans into an infrastructure in which they can be controlled and exploited — how this might simply be American slavery, reinvented.

Note that the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution reads, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

In other words, if slavery is only legal for prisoners, then you simply have to get the former slaves into prison to exploit their labor once more.

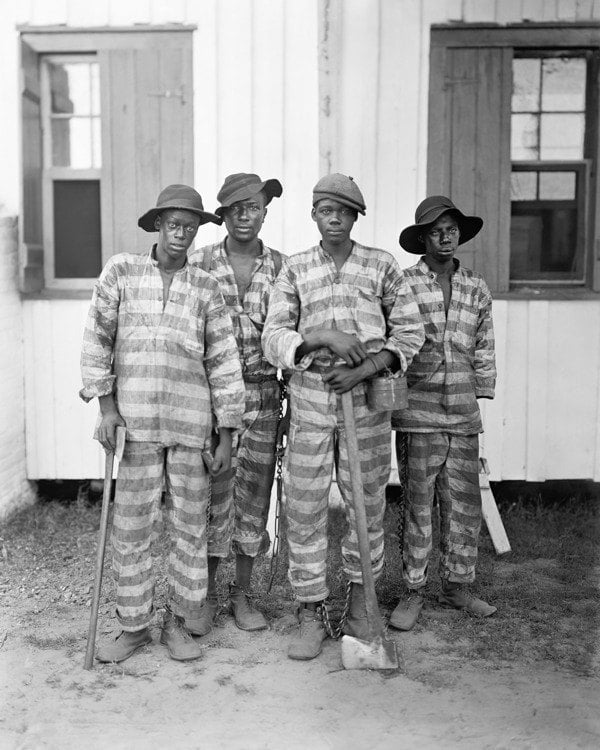

Child inmates at work in the fields, 1903. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

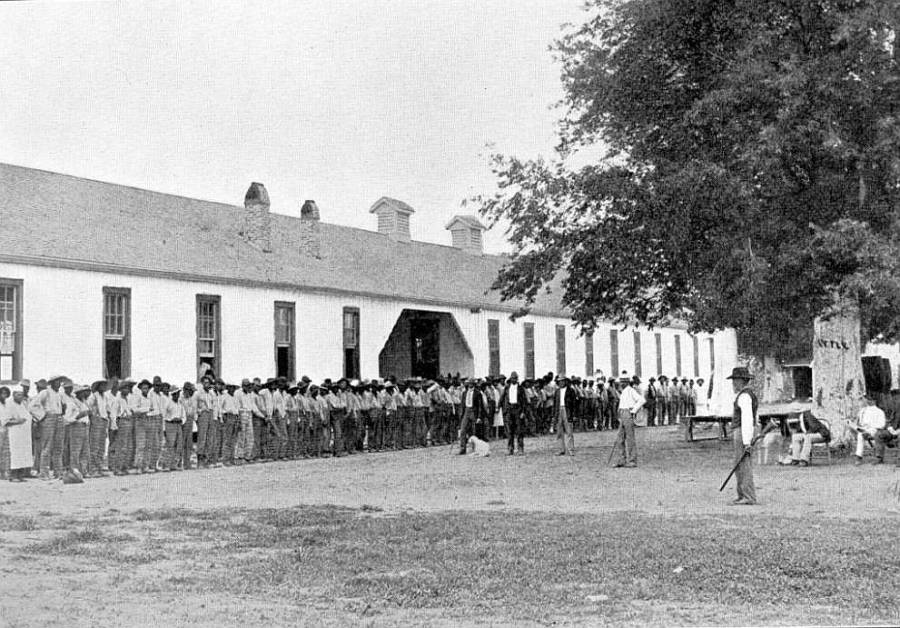

This reading of history comes into even sharper focus when you realize that the roots of today’s private prisons can be found in the convict leasing system of the Reconstruction era South. Under this system, prison labor (including that of many prisons built upon former plantations) could be contracted out to private businesses (including many former plantation owners). It was, of course, as seen in PBS’ comprehensive documentary on the subject, just “slavery by another name.”

Southern chain gang, 1903. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Even today, the largest maximum security prison in the United States is the Louisiana State Penitentiary, a former plantation still nicknamed “Angola,” after the country from which many of that plantation’s slaves came.

Angola, circa 1901. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

And it’s only fitting that such a prison would be in Louisiana, the state with the highest incarceration rate in the country. Just behind Louisiana sit Oklahoma, Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and all the other Southern states where slavery was once king.

Private prisons in particular (be they run by CCA or GEO, both founded in Southern states) are far more common in the South.

And it’s likely that private prisons are only going to become more and more common. While the raw number of U.S. prisoners in private state and federal prisons has actually fallen slightly from its 2012 high, the number in private detention facilities for illegal immigrants has soared. Moreover, new private prisons are opening up every year.

An immigrant detainee in his cell at GEO’s Adelanto Detention Facility in Adelanto, California. Photo: John Moore / Getty Images

Both CCA and GEO open their 2015 annual reports to their investors with the “good” news that they opened new facilities last year. CCA constructed 6,400 new beds, acquired 3,700 others, and received a contract for 1,000 more. GEO added 15,000 beds.

“Beds” is the word both CCA and GEO routinely use, but what they’re talking about are human beings and profits.

Now, let’s make the pathway to those profits perfectly clear: Private prisons spend millions greasing a legal system that puts citizens, especially African-Americans, behind bars at a rate unprecedented throughout the world, even though crime has lessened. This way, prisons can exploit inmate labor to make money, part of which is then used to grease the system once again. The wheel goes round and round.

By virtue of their trade, CCA, GEO, and all other private prisons have zero interest in stopping that wheel. That means getting more and more people behind bars. To that end, it’s not just that the U.S. prison population is booming overall, it’s that the recidivism rate is doing the same.

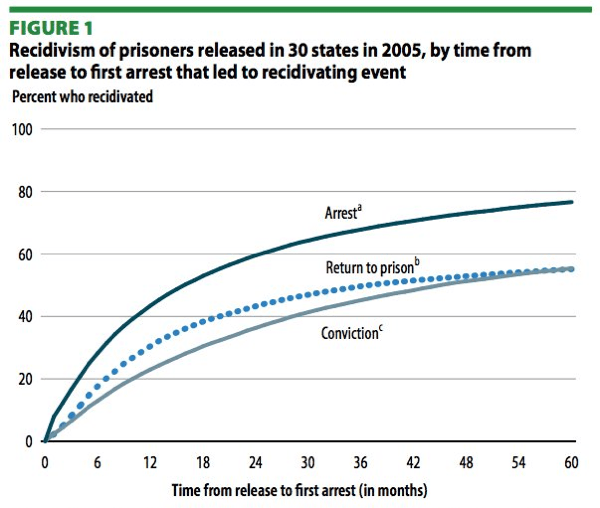

Source: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics report from 1983 (the year CCA was founded), the percentage of prisoners re-arrested for another crime within three years of being released from prison was 62.5 percent. When they did the study again in 1994, that figure had increased to 67.5 (with recidivism for drug offenses shooting up by 16 percent). By 2005 (the last available study), it had reached 71.6.

Although CCA and GEO repeatedly make a show of claiming that they’d like to see that number go down, they have a strong, clear interest in seeing it go up.

In those 2015 reports to investors, both corporations’ CEOs open their letters by claiming that they’re committed to “reducing recidivism” and “breaking the cycle of crime,” while, within the very same sentence, touting the construction and acquisition stats on how many new people they’ll be able to imprison in the coming years.

Justin Sullivan / Getty Images

Perhaps they’re hoping that we’d prefer to ignore or refuse to notice what’s becoming increasingly obvious about an ever-growing sector of crime and prisons in the U.S.: It’s not a justice system, it’s a business.

Next, go beyond private prisons and discover more appalling facts on modern slavery around the world. Then, step inside the five worst prisons on the planet, and see what slavery once looked like in the U.S. with these harrowing images from 1830s anti-slavery almanacs.