How Project Chariot came close to detonating thermonuclear weapons in Alaska, and still managed to poison the area's natives with radioactive waste for decades afterward.

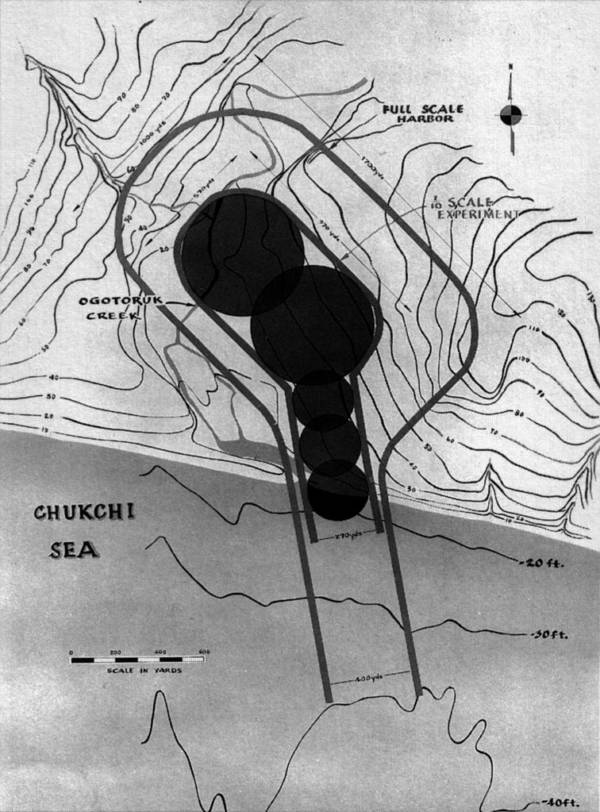

Wikimedia CommonsThe plans for Project Chariot, with the circles representing the five thermonuclear explosions that would create the harbor.

In 1958, the year before Alaska reached statehood, the U.S. government proposed the creation of a manmade harbor near the territory’s Chukchi Sea — by detonating nuclear explosives.

The operation was dubbed Project Chariot. And although it went belly-up before any explosives were ever planted, it had a lasting impact on the area.

By the late 1950s, the word “atom” was laden with immeasurable weight. As nuclear stockpiles expanded, doomsday loomed in the backs of everyone’s minds. In spite of this, some were awfully optimistic about the destructive technology’s potential for good.

In 1957, the United States launched Operation Plowshare to investigate alternative uses for nuclear weapons. The project was named after a passage in the Bible about turning swords into the blades on a plow, which are called plowshares.

To this end, most of the government’s nuclear testing took place at a remote site in Nevada, but Alaska’s impending statehood meant miles of frozen testing ground were soon to be available. There in Alaska they hatched a plan to use five thermonuclear explosions to create a new deep-water port on the Chukchi Sea, a port that would bolster the economy by allowing for the exporting of coal during the three months out of the year during which the water wasn’t frozen.

However, not long after the plan was proposed, it received backlash from activists, scientists, and locals. At the time, many residents of nearby Point Hope were still living in sod houses and speaking Inupiat. The resulting explosion would contaminate their caribou hunting grounds and upset fishing and whaling in the Chukchi Sea, which would seriously rupture their way of life.

Meanwhile, the plan became a point of contention in the science world. In 1961, articles and letters analyzing Project Chariot reports by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) appeared in Science Magazine, a peer-reviewed journal. According to a letter published in August 1961 by Science in response to an article published the issue before, the AEC reports were based on four tests at their Nevada test site. The AEC reports themselves stated it would be a “great stretch of one’s imagination” to predict the outcome of an explosion on the Chukchi Sea based on these four tests.

By 1962, Project Chariot was seemingly finished, at least on paper.

That same year, however, the United States began secretly testing the effects of radioactivity on Arctic soil 25 miles south of Point Hope using leftover waste from the Nevada tests (some of which had a half-life of some 30 years). They buried the materials in a dozen pits, studied the results, and finally reburied the materials in a shallow mound. There weren’t even any signs or fences marking the dump site.

This plot was discovered in the early 1990s by University of Alaska researcher Dan O’Neill, and locals became justifiably angry at the cover-up. Although only around 700 people reside in Point Hope, it is one of the longest consistently lived-in areas in North America, and the dump site sat right in the middle of the local hunting grounds. The area has one of the highest cancer rates in the country.

The discovery led to a 20-year clean-up that finally wrapped up in 2014 to little fanfare and a halfhearted apology.

Next, see some of the most unbelievable photos that reveal the reckless history of U.S. nuclear testing. Then, watch an underground nuclear test cause the Earth to crumble.