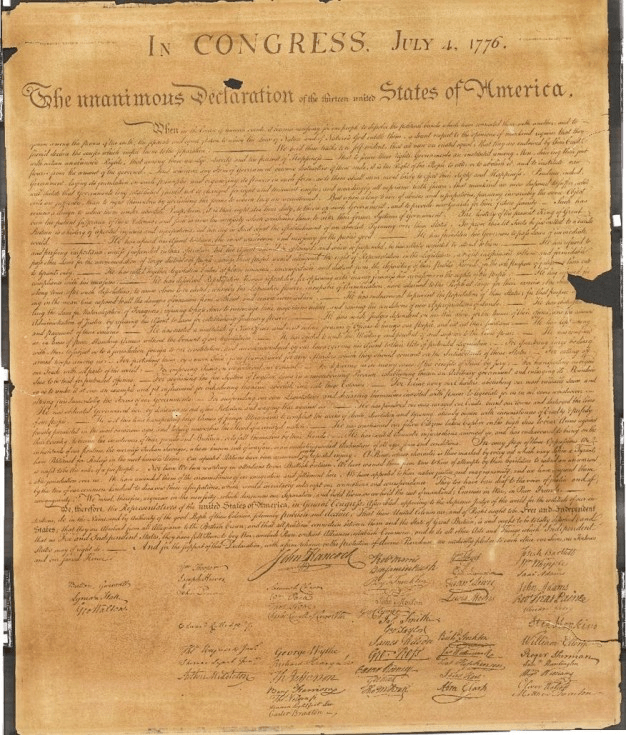

The engraving dates to 1820, when John Quincy Adams commissioned parchment copies to be made for workaday use by politicians. It's one of only eight printed on paper.

American Philosophical SocietyDetailed etchings found on this letter “C” clued researchers into the fact that this was no ordinary facsimile copy of the Declaration of Independence.

After nearly two decades of study and analysis, researchers in Philadelphia have verified a new and extremely rare 19th-century copy of the Declaration of Independence. It was discovered in the archives of the American Philosophical Society in 2002 but only authenticated recently.

According to The Philadelphia Inquirer, the society had actually been in possession of the artifact since 1842, when Daniel Webster, then Secretary of State, gifted it to the institution, but modern conservators believed it to be a cheap knockoff.

The version dates to 1820 when John Quincy Adams commissioned William Stone to make copies from the original Declaration of Independence with signatures. Fearful the original document was becoming too worn for use, Adams ordered Stone to take engravings and print 201 parchment copies.

This copy, however, was printed on paper. Until now, only seven of these copies were thought to exist.

“The APS holds one of the rarest Stone Declaration copies anywhere in the world,” said APS Librarian Patrick Spero. “This is only the eighth known copy. We were missing one piece and that was a Stone Declaration and that’s what we discovered we do, in fact, have.”

According to Fox 29, Anne Downey began pondering the document’s legitimacy more than 20 years ago. As Head of Conservation at APS, she only discovered upon treating the piece for preservation that it reacted in a manner not indicative of a lithograph or parchment — and that it was, indeed, a rare paper copy.

American Philosophical SocietyThis is now the eighth known paper copy printed by William Stone.

Adams was Secretary of State when he ordered Stone to make exact engravings, noting how worn and fragile the original copy of the Declaration was becoming already in the early 19th century. (It now sits in the National Archives securely encased behind protective glass.)

Stone spent three years on the project, meticulously engraving every serif and flourish of the original Declaration, resulting in copper-plated renderings in 1823.

From those renderings, he issued 201 copies on animal parchment. These he gave to the surviving signers of the original document and various political figures, including some historical institutions. It remains unclear how many paper copies Stone printed. The first was only discovered and verified in 2002.

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence (1819).

It was around that time that the APS, which was founded in 1743, dusted off a substantially varnished copy from its archives. As Head of Manuscripts Processing, Valerie-Ann Lutz believed she had encountered one of the original 201 parchment copies.

“She got very excited,” said Downey. However, her excitement would be short-lived.

In 2013, expert on American documents and Stone printings Seth Keller was contacted to analyze the document.

“He took a look at it, and he said, ‘Well, no, it’s not,’ and he just sort of brushed it off, and, I guess, assumed it was just some sort of cheap Victorian facsimile,” said Downey.

Fortunately, another historian needed the document for research purposes in 2015 and renewed speculation of where it came from. Downey was asked to treat the document for conservation, and noted it was extremely fragile, torn, and browned.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in the National Archives building where the original declaration sits.

“He said: ‘Well, you know, it’s dang brittle. We need to be able to access it once in a while, for researchers, so we can go ahead and treat it. We don’t know what it is — it’s probably a piece of Victorian junk,'” recalled Downey.

It was only after removing the glue and varnish and washing the document that she spotted shadows around the letters and hatch marks left from etching the first large capital “C” in the opening words: “In Congress, July 4, 1776.”

To Downey, these were clear signs of having been engraved by hand. It was now evident this was no Victorian reproduction at all but an early American official engraving.

“I said, ‘I have to stop treatment, something’s happening, I’m seeing something very unusual,'” said Downey. “It’s unbelievable. It’s the highlight of conservator’s career.”

Ultimately, how paper copies Stone made of the Declaration of Independence remains to be seen. With potentially many more relegated to dusty shelves across the United States, it’s quite likely that experts such as Downey and Lutz will continue to uncover them.

“They are not just dead documents,” said Spero. “People are doing research in them all the time and making new discoveries and this is just one example of that.”

After reading about the rare copy of the Declaration of Independence uncovered by the American Philosophical Society, learn about the long-lost Abraham Lincoln deathbed photo. Then, discover who really made the American flag.