After World War II, thousands of Nazi war criminals escaped justice with the help of ratlines — which were set up by the Vatican, South American politicians, and sometimes even U.S. spies.

As the dust settled after World War II, scores of Nazis tried to escape punishment for their crimes by fleeing Europe. And thousands made their way to South America through secret networks nicknamed “ratlines.”

Helped by South American politicians, the Vatican, and even U.S. intelligence, Nazi war criminals successfully traversed escape routes from Europe to countries like Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. Some of them were eventually located and brought to justice. But many more Nazis were never captured.

This is the shadowy story of ratlines, the spidery system of escape routes created by American spies, South American politicians, Vatican officials, and other individuals who helped Nazi war criminals flee Europe.

The Emergence Of Ratlines After World War II

The word “ratline” comes from the sea. According to Slate, it refers to ropes near a ship’s mast, which sailors might have climbed while trying to survive a sinking ship. But after World War II, it took on a different connotation.

Then, thousands of Nazis seeking to flee Europe did so via the so-called ratlines that offered an escape route to various countries in South America, mostly to Chile, Brazil, and Argentina. They were assisted in large part by Argentine President Juan Peron, who had grown to admire European dictators like Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

Hulton-Deutsch/Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty ImagesThe Nazi ratlines were greatly assisted by Argentine President Juan Peron.

The Guardian reports that Peron’s admiration stemmed from his time as a military attaché in Italy and his relationships with SS agents. Additionally, Peron saw the Nuremberg trials as an “insult to military honor” and sought to bring scientists, engineers, and nuclear experts into Argentina.

So, in 1946, History reports that Peron enlisted Argentine Cardinal Antonio Caggiano to open a dialogue with his French counterparts. Caggiano then let them know that Argentina would be willing to accept Nazi collaborators.

The ratlines were officially open. And before long, others would join Peron in helping Nazis escape from Europe and start new lives in South America.

How Nazis Escaped To South America

According to Deutsche Welle, the ratlines did not have any formal structure. Rather, they emerged spontaneously after World War II. But many Nazis who escaped via the ratlines followed a similar path across the Alps to Italy.

Once in Italy, many Nazis followed the “monastery route,” which allowed them to hide out in local monasteries. Most then traveled to Rome, where they were assisted further — sometimes by American and British spies and sometimes by prominent members of the Catholic Church.

As Philippe Sands, the author of The Ratline, told NPR, American and British spies helped Nazis for a single reason: to fight communism.

Wikimedia CommonsAlois Hudal, an Austrian bishop based in Rome who helped Nazis traverse ratlines to South America.

“They were virulently anti-communist,” Sands explained. “In 1948 and ’49, there was a tremendous concern amongst the British and the Americans in particular that Italy would be the launching pad for the Soviet Union… the British and the Americans started recruiting [Nazis] and, indeed, I think, used the ratline, the escape route to Argentina, as a recruitment tool.”

At the same time, many Nazis found refuge within the Vatican. For instance, Bishop Alois Hudal helped Nazis because he believed they were “completely blameless” and that by helping them escape he “snatched them from their tormentors with false identity papers,” according to Deutsche Welle.

These “false identity papers” helped Nazis get passports from the International Committee of the Red Cross, which they then used to sneak out of Europe (usually through ports in Italy or Spain) without being detained.

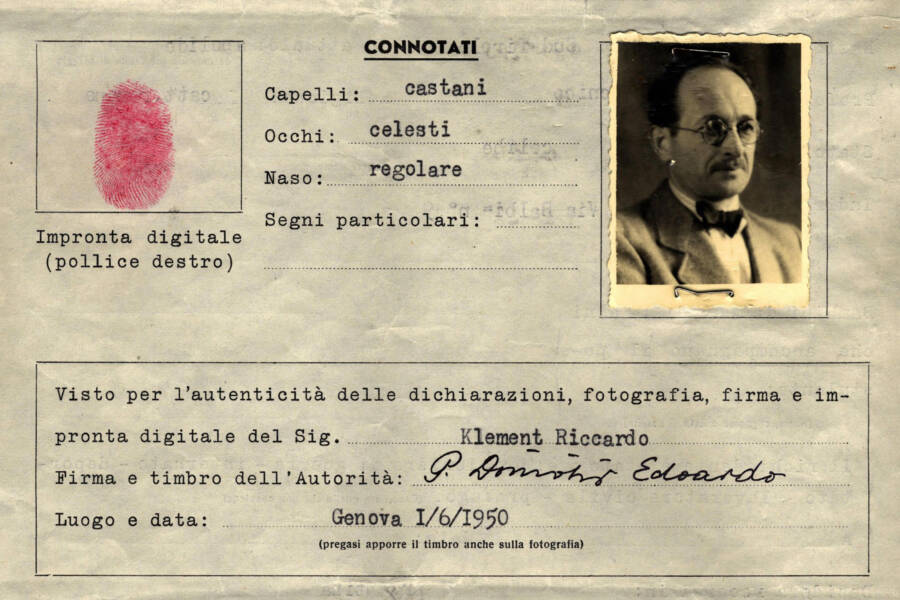

HO/AFP via Getty ImagesA Red Cross travel document for Nazi Adolf Eichmann, which lists his name as “Ricardo Klement.”

With this help, thousands of Nazis were able to escape from Europe to South America. History estimates that between 500 and 1,000 went to Chile, up to 2,000 relocated to Brazil, and as many as 5,000 fled to Argentina.

So who were they?

The Nazis Who Traveled Along Ratlines

Following World War II, countless Nazi war criminals escaped Europe via ratlines to South America, where they could start anew.

“It was with a sense of deliverance, of escape, a veritable joy in the heart, that I boarded the plane that would carry me to South America,” Nazi collaborator Pierre Daye said, according to The Guardian. “They may be looking for me in that troubled Europe. But they cannot reach me. I fly far from a world gone mad, towards peace. It’s all over. I have escaped.”

Other infamous Nazis who escaped in this way included Adolf Eichmann, Josef Mengele, Klaus Barbie, Franz Stangl, and more.

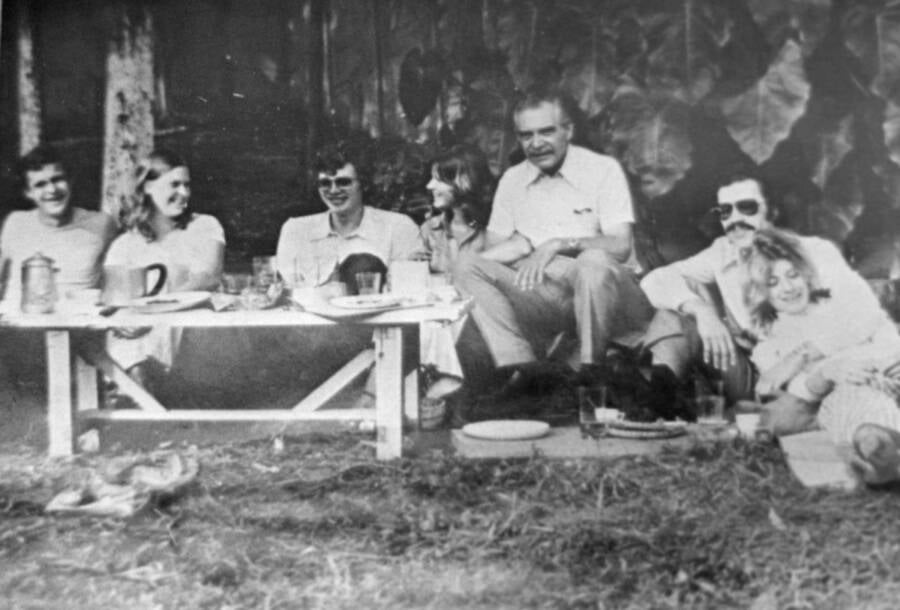

Bettmann/Getty ImagesJosef Mengele, believed to be the third man from the right, in Brazil.

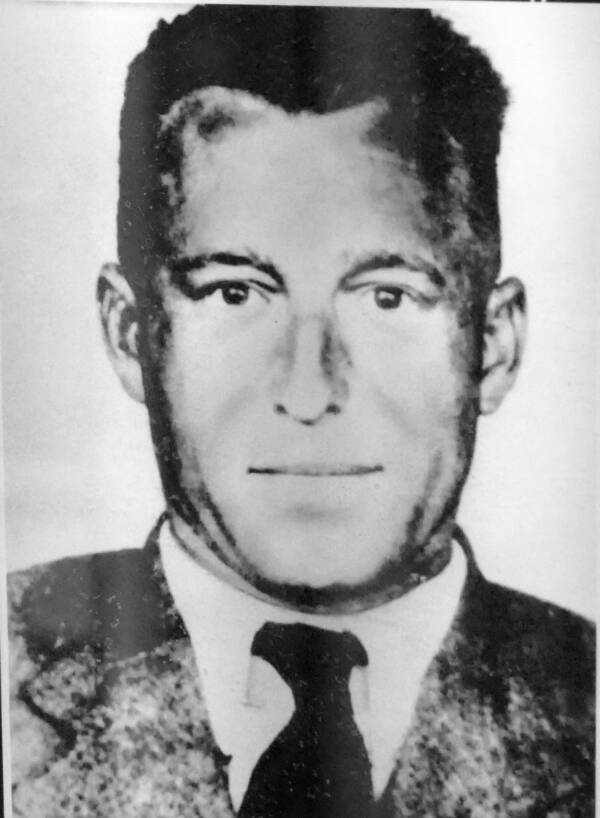

Eichmann, an architect of Adolf Hitler’s “Final Solution” to exterminate European Jews, was able to escape Europe with the help of a Franciscan monk. Mengele, who conducted cruel medical experiments at concentration camps, including on children, fled to Argentina through Italy with the help of the Catholic Church. Barbie was helped by American anti-communist spies, and Stangl was helped by Bishop Hudal.

“You must be Franz Stangl — I’ve been expecting you,” Hudal said to Stangl, according to Deutsche Welle, before handing the man who was once nicknamed “White Death” forged documents to assist his escape.

Even Adolf Hitler himself was rumored to have escaped to Argentina, though historians generally agree that this conspiracy theory is not true.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesFranz Stangl, known as “White Death,” was the commandant of the Sobibor and Treblinka death camps.

Safe in South America, Nazis who were responsible for the deaths of thousands settled into their new lives. Eichmann began again in Buenos Aires with his family. Mengele floated between Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil. Barbie hid out in Bolivia, and Stangl snuck into Brazil via Syria.

“In those days, Argentina was a kind of paradise to us,” Nazi Erich Priebke, who’d approved the transfer of 2,000 Roman Jews to Auschwitz, remembered fondly in 1991, according to The Washington Post.

But not all Nazis were able to escape. Some, like Rudolf Höss, attempted to flee but were tracked down, put on trial, and executed for their crimes. And “paradise” wouldn’t last for all of the Nazis who escaped to South America via ratlines. Before long, Nazi hunters would come looking for them.

What Happened To The Nazis In South America?

Though the Nazis who settled in South America may have hoped to live the rest of their lives in obscurity, many people were not so quick to forget their crimes. According to History Extra, Nazi hunters soon set out for revenge.

Entities like Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency, and individuals like Fritz Bauer, a district attorney in West Germany, worked tirelessly to ensure that justice was served. In 1960, Israeli intelligence agents kidnapped Eichmann, then brought him back to Israel and sentenced him to death.

In 1967, Stangl was located thanks to help from a Holocaust survivor named Simon Wiesenthal and sentenced to life in prison in West Germany. In 1983, Barbie was extradited to France, where he died while serving a life sentence.

John Milli/GPO via Getty ImagesAdolf Eichmann during his 1961 trial in Israel.

Mengele, on the other hand, managed to avoid detection and capture. He ultimately drowned off the coast of Brazil in 1979 after suffering a stroke, and it wasn’t until 1985 that forensic testing revealed his true identity.

Indeed, despite some high-profile arrests of Nazis living in South America, many who escaped Europe via ratlines managed to live out the rest of their lives in their new homes. Eduard Roschmann, who allegedly killed tens of thousands of Jews in Latvia, died in Paraguay in 1977. Walter Rauff, who killed an estimated 100,000 with his mobile gas chambers, died in Chile in 1984.

They, and thousands of others, successfully used the ratlines to escape to South America after World War II. These Nazis were able to disappear into new names and new lives and avoid prosecution for their crimes.

But questions about the ratlines remain. For starters, historians are curious how much Pope Pius XII knew about the ratlines that helped Nazis.

“Did the pope issue direct instructions or was it a more general order to help people without papers?” historian Hubert Wolf asked. “Or is there concrete evidence that the pope, with encouragement from the CIA, thought: ‘It would be a good idea to send nationalistic people to Latin America because Communists were actively trying to overthrow the continent?'”

For now, questions like this one don’t have an answer. But what’s certain is that thousands of Nazis — like sailors fleeing a sinking vessel — used the ratlines to escape justice in Europe. Though some were eventually hunted down, many more simply disappeared into South America forever.

After reading about the ratlines used by Nazis after World War II, look through these chilling photos that illustrate the Nazis’ rise to power. Or, discover the stories of some of the resistance fighters of the war.