The 28,000-year-old woolly mammoth was dug out of Siberian permafrost in 2011. Now scientists have found that its DNA is partially intact.

Kindai UniversityYuka, the 28,000-year-old mammoth.

In 2011, an impressively well-preserved woolly mammoth was dug out of the Siberian permafrost. With the species having met its extinction some 4,000 years ago, finding such a relatively pristine specimen was an astounding feat — particularly since this one was 28,000 years old.

Scientists have since been eagerly studying the uncovered mammoth in an attempt to learn how viable its biological materials still are, all these millennia later. In a study published in Scientific Reports, it’s clear that substantial progress has been made in that attempt.

According to Fox News, cells from the 28,000-year-old specimen have shown “signs of biological activities” after being infused into mouse oocytes — cells found in ovaries that are capable of forming an egg cell after genetic division.

“This suggests that, despite the years that have passed, cell activity can still happen and parts of it can be recreated,” said study author Kei Miyamoto from the Department of Genetic Engineering at Kindai University. “Until now many studies have focused on analyzing fossil DNA and not whether they still function.”

Wikimedia CommonsA display of the woolly mammoth in the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, Canada.

The process to establish whether the mammoth DNA could still function wasn’t easy. According to IFL Science, researchers began by taking bone marrow and muscle tissue samples from the animal’s leg. These were then analyzed for the presence of undamaged nucleus-like structures, which, once found, were extracted.

Once these nuclei cells were combined with mouse oocytes, mouse proteins were added, revealing some of the mammoth cells to be perfectly capable of nuclear reconstitution. This, finally, suggested that even 28,000-year-old mammoth remains could harbor active nuclei.

Five of the cells even showed highly unexpected and very promising results, namely signs of activity that usually only occur immediately preceding cell division. The study maintains, however, that there’s much work left to be done.

“In the reconstructed oocytes, the mammoth nuclei showed the spindle assembly, histone incorporation and partial nuclear formation; however, the full activation of nuclei for cleavage was not confirmed,” the study said.

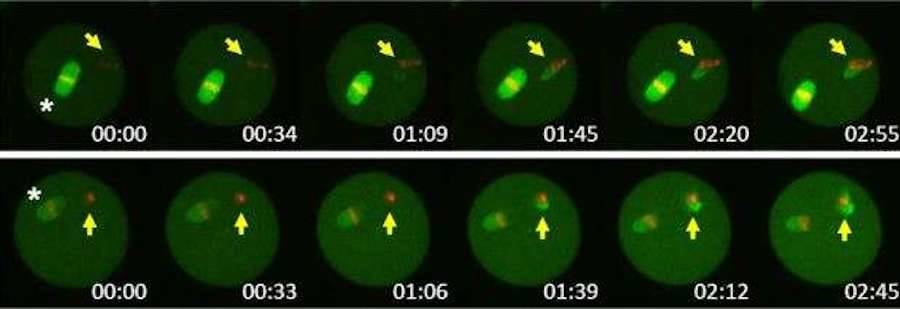

The below image represents a time-lapse of oocytes injected with mammoth nuclei.

Kindai University/Scientific ReportsA time-lapse of mouse oocyte cells injected with mammoth nuclei.

“We want to move our study forward to the stage of cell division, but we still have a long way to go,” said Miyamoto.

While most mammoths died out between 14,000 and 10,000 years ago, this particular mammoth — which the research team has dubbed “Yuka” — belonged to a resilient population of the species that managed to live in the Arctic Ocean’s Wrangel Island until 4,000 years ago.

The discovery that Yuka’s ancient cells have shown signs of structural DNA integrity, while not confirming the ability to bring the species out of extinction, does complement longstanding research efforts in the scientific community to do just that.

While Miyamoto admits that “we are very far from recreating a mammoth,” plenty of researchers attempting to use gene editing to do so are confident that that achievement is around the corner. Recent efforts, using the controversial CRISPR gene editing tool, are arguably the most promising, of late.

Harvard and MIT geneticist George Church, who co-founded CRISPR, has been leading the Harvard Woolly Mammoth Revival team for years now in an attempt to introduce the animal’s genres into the Asian elephant — for environmental purposes related to climate change.

“The elephants that lived in the past — and elephants possibly in the future — knocked down trees and allowed the cold air to hit the ground and keep the cold in the winter, and they helped the grass grow and reflect the sunlight in the summer,” he said.

“Those two (factors) combined could result in a huge cooling of the soil and a rich ecosystem.”

As it stands, Miyamoto’s team is focused on reaching the stage of cell division — and with the progress made thus far, his efforts seem rather promising.

After learning about the 28,000-year-old mammoth cells showing signs of biological activity, read about de-extinction and what goes into the process. Then, learn about an extinct 12,000-year-old lion species being considered for de-extinction.