Robert Johnson was a guitar virtuoso who played across the South in the early 1900s, but much of his life remains a mystery, leading fans to fill in the blanks with outlandish myths.

Robert Johnson was one of the greatest blues musicians who’s ever lived. But not much is known about the man, whose unique playing style and imaginative lyrics influenced generations of music icons, from B.B. King to Bob Dylan to The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin.

A whiz on the guitar — Eric Clapton said that when he first heard a Johnson recording, “I realized that, on some level, I had found the master” — his brief life and mysterious upbringing fueled the legend that he sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his preternatural talent.

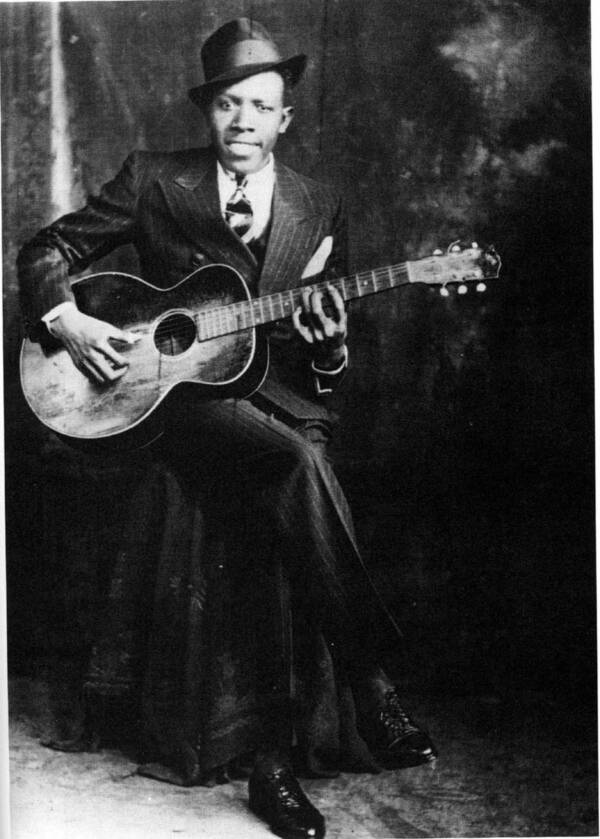

Delta Haze CorporationOne of two confirmed authentic photographs of Delta blues king Robert Johnson, found in the possession of his half-sister.

The public has only ever seen two confirmed pictures of Johnson, and most of what we know about him comes from scant historical records and oral history.

But did Robert Johnson really make a deal with Satan to gain his gift?

Robert Johnson: The Man Before The Myth

Not much is known about Robert Johnson’s early life, though some facts have come to surface in recent years. We know now that he was born Robert Leroy Johnson in Hazlehurst, Mississippi sometime in May 1911. He was born out of wedlock after his mother, Julia Major Dodds, had an affair with a field hand named Noah Johnson.

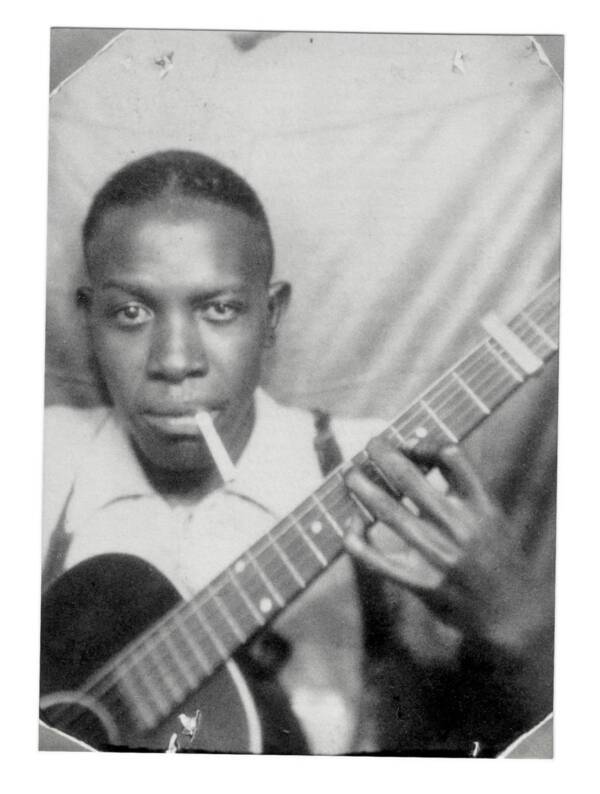

Delta Haze CorporationSecond confirmed portrait of Robert Johnson. A third photograph purported to be of Johnson was published in Vanity Fair in 2008, but later dismissed by historians.

Julia’s husband, a successful farmer and carpenter named Charles Dodds, fled town before Johnson was born on account of his sharing a mistress with an Italian businessman named Joseph Marchetti. Three black men had already been lynched in Hazlehurst that year, and Charles Dodds didn’t want to be the fourth.

Disguising himself as a woman, Dodds escaped to Memphis, Tennessee, leaving Julia destitute. Most of her 10 children followed their father to Memphis, and soon after she had Robert.

When Robert Johnson was 7, his mother remarried and moved him to Robinsonville, Mississippi.

Reluctant to pick cotton, Johnson instead turned to the guitar and the diddley bow, a string nailed to the side of a shack with a glass bottle nestled in it as a bridge. The diddley bow was his introduction to music-making.

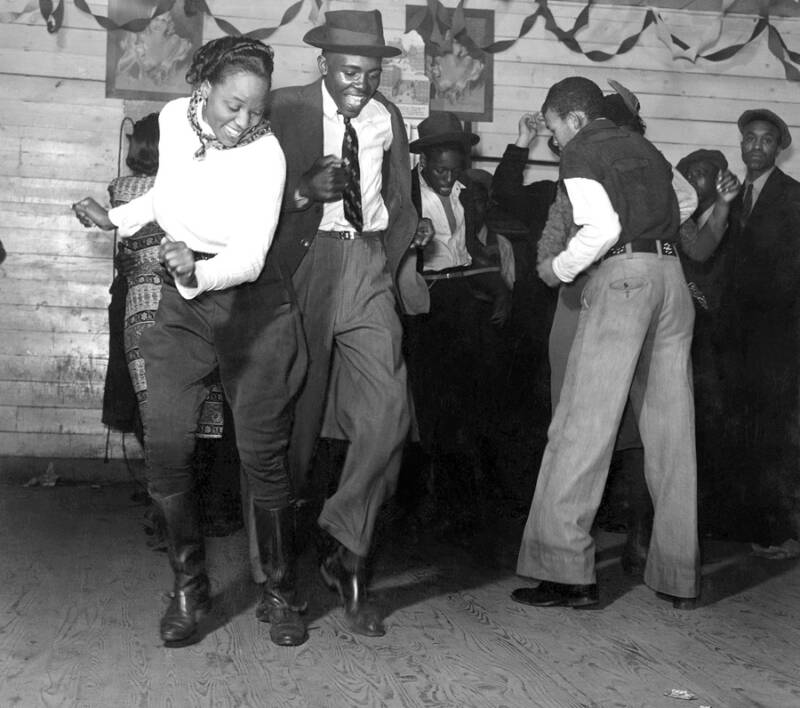

He spent a lot of time at juke joints, stores, and private homes where black residents could mingle and dance after hours. Watching early pioneers of Delta blues, like Son House and Willie Brown, fueled his desire to pursue music professionally.

But those ambitions came to a halt when he married his first wife, Virginia Travis. When they wed, Johnson was 17 and Virginia was 14 (though they both lied and said they were older on their marriage certificate). He loved her so much that once she got pregnant, he gave up music entirely to earn money working in the fields.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty ImagesPatrons dancing at a juke joint near Clarksdale, Mississippi, circa 1940.

As the baby’s due date approached, Travis left their home in northwestern Mississippi for her childhood home in Penton, so her family could help care for the newborn. Johnson followed her but made stops along the way to perform his music.

By the time Robert Johnson arrived at the Travis house, his wife and child had already been buried; both had died during the difficult birth. Travis’ ultra-religious family, seeing Johnson arrive with a guitar in his hand, blamed their deaths on his “devil’s music.”

It’s perhaps the first link between Robert Johnson and the devil myth, and contemporary scholars believe that the deaths of his wife and child pushed a 19-year-old Johnson back into his musical ambitions.

Robert Johnson, King Of The Delta Blues

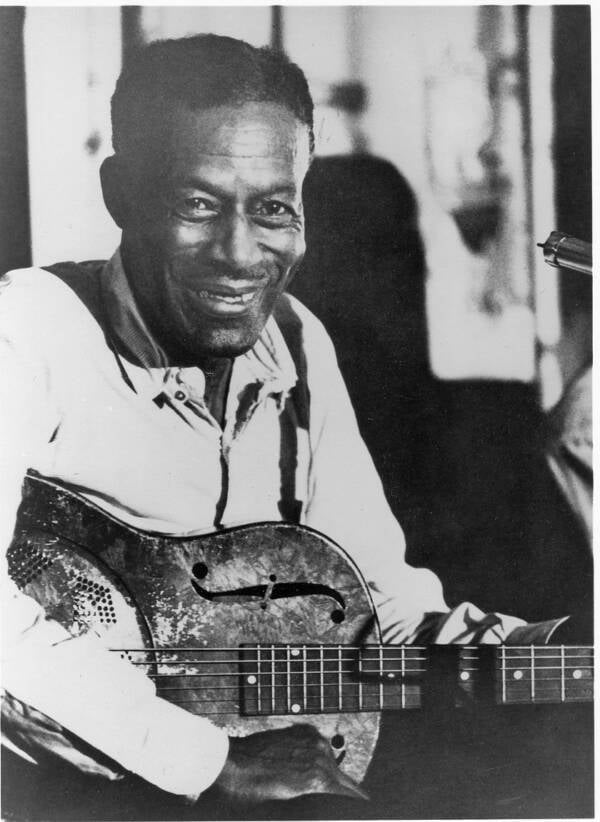

Wikimedia CommonsBlues legend Son House knew Johnson and later recalled his sudden transformation from amateur player to the king of the Delta blues.

At age 19, Robert Johnson performed on street corners here and there, but he was nowhere near an exceptional musician. Yet he was self-assured and took any chance he could get to perform.

During Son House’s and Willie Brown’s shows in Robinsonville, Johnson would take one of their guitars during intermission and force the audience to listen to his tunes.

“Folks they come and say, ‘Why don’t you go out and make that boy put that thing down? He running us crazy,'” House recalled in a 1997 interview for the documentary about Johnson called Can’t You Hear the Wind Howl. The jeering was enough to push Johnson out of town altogether.

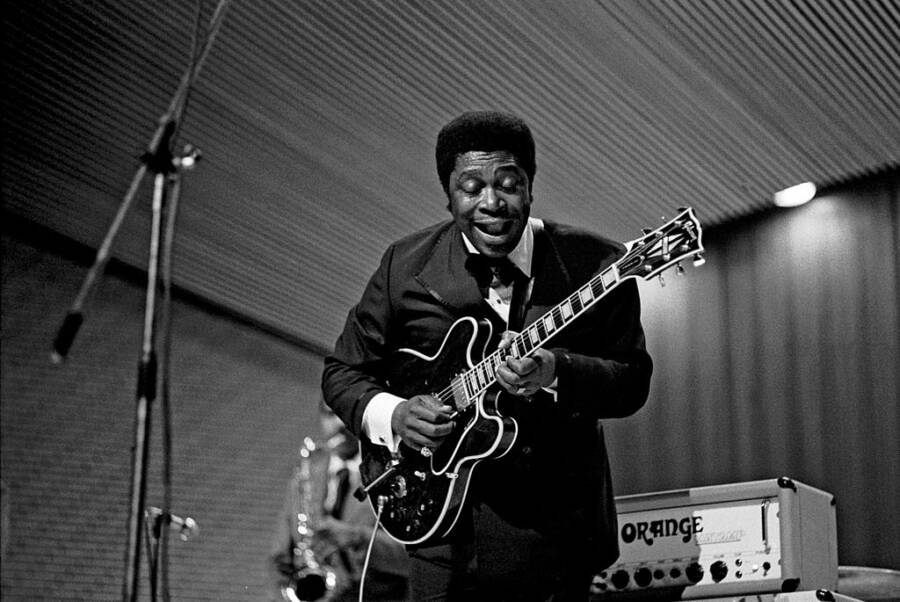

Wikimedia CommonsBlues powerhouse B.B. King, a fellow Mississippi native who was heavily influenced by Robert Johnson’s style of playing.

Nobody heard from Johnson again — until months later, when he showed up at another House and Brown show in Banks, Mississippi. Johnson asked House for permission to play a piece onstage and, perhaps feeling sorry for the guy, House let him.

As soon as Robert Johnson began plucking his guitar, it was clear he was no longer the same desperate musician that had been booed off the stage just a little while earlier. His playing sounded like the work of two musicians, his long, lithe fingers expertly strumming his guitar’s seven strings. His vivid lyrics – at once colorful and mournful — spilled out of him with a throaty passion.

“He was so good!” House said. “When he finished all our mouths were standing open. I said, ‘Well, ain’t that fast! He’s gone now!'”

Johnson’s genius artistry had seemingly come out of nowhere.

Wikimedia CommonsMusician David Honeyboy Edwards played with Robert Johnson as they traveled together to perform across Mississippi.

“Man, we played for a lot of peoples,” Delta blues legend David Honeyboy Edwards, a friend of Johnson’s, told the New York Times before his own death in 2011. “We would walk through the country with our guitars on our shoulders, stop at people’s houses, play a little music, walk on.”

Robert Johnson took up with another young girl named Virgie Cain, who became pregnant with his child. But Cain, just like Johnson’s late wife, came from a religious family who forbade her from contacting him.

After that, Johnson began drinking, womanizing, strumming, and crooning his way through the Delta.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=It-tJ8DOjIk

In 1936, Johnson finally landed a chance to record his music, a golden opportunity arranged by the American Record Company in San Antonio, Texas. He recorded his first single, “Terraplane Blues,” which sold 5,000 copies and earned him another recording session. He played into a corner of the recording booth — either because he liked the sound of the reverberation, or because he didn’t want to give away his musical secrets.

But before he could amply enjoy his success, Johnson died suddenly a year later. He was only 27 years old — the same age as so many other music legends when they died.

Sean Davis/FlickrAnother Robert Johnson tombstone, this one located in Craigside, Mississippi. Nobody knows exactly where the blues legend was laid to rest.

Did Robert Johnson Really Sell His Soul To The Devil?

As the legend goes, after a teenage Robert Johnson was booed off the stage in Robinsonville, he went to a Mississippi crossroad at midnight and summoned the devil. The devil promised to endow him with supernatural musical abilities — as long as the musician gave up his soul in return.

Historical records show that he actually learned how to play from a blues guitarist named Isaiah “Ike” Zimmerman (sometimes spelled Zinnerman), but the devil myth has stuck around for decades — egged on by elements of Johnson’s life and music.

PixabayLegend has it Robert Johnson got his musical abilities by making a deal with the devil at a crossroad at midnight.

There are conflicting reports over how long Robert Johnson disappeared. Some say he was gone for six months, others say it was closer to a year and a half. Zimmerman and his wife, Ruth, took Johnson into their home in Beauregard, Mississippi, while the established player mentored Johnson.

The pair’s favorite spot to practice was among the tombstones at the Beauregard Memorial Cemetery across from Zimmerman’s house. According to Johnson’s grandson, Steven, the senior guitarist brought Johnson there so they could play undisturbed — but also so they wouldn’t disturb others.

“Ike told my granddad, ‘Robert, look, I don’t care how bad you sound out here. Nobody out here is going to complain,” Steven said. But their habit of playing music in the graveyard no doubt perpetuated the myth that the two had dealings with the devil.

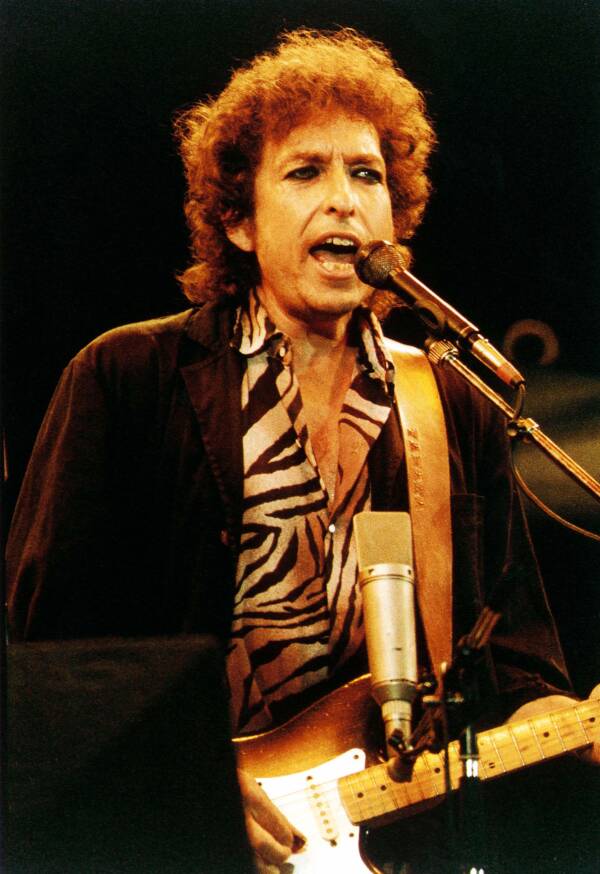

Pete Still/RedfernsBob Dylan said that he drew inspiration for hundreds of his songs from Robert Johnson’s music.

Zimmerman’s youngest daughter, Loretha Z. Smith, recalled how her father taught Robert Johnson how to slide his fingers seamlessly across the guitar strings. In fact, Smith’s family believes that at least four of Johnson’s songs can be attributed to Zimmerman: “Walking Blues,” “Ramblin’ On My Mind,” “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom,” and “Come On In My Kitchen.”

A Legacy That Has Stood The Test Of Time

Robert Johnson mysteriously died in Greenwood, Mississippi on August 16, 1938, but his death certificate didn’t list a cause.

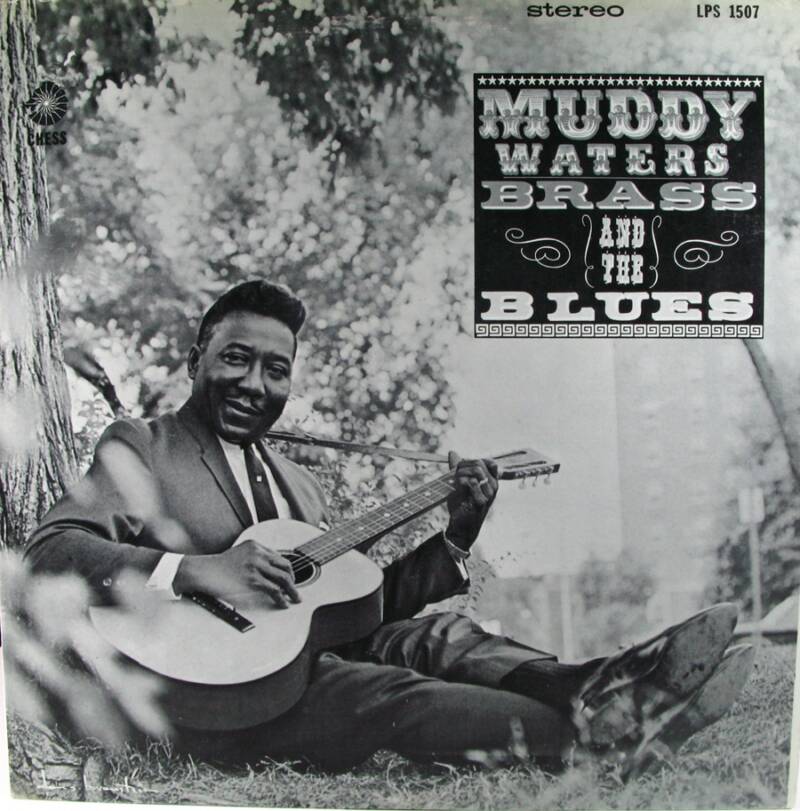

Kevin Dooley/FlickrMuddy Waters, another blues icon, was also influenced by Johnson’s songs.

What — or who — killed Johnson is still the subject of wide speculation. Many believe that the jealous husband of a woman he was having an affair with poisoned Johnson’s whiskey. Decades after he died, someone checked the back of his death certificate and found a note saying the owner of the plantation where Johnson died thought he’d been killed by syphilis.

Sadly, if he had been alive just four months later, Robert Johnson could have performed at Carnegie Hall in New York City.

John Hammond, later an executive at Columbia Records, was organizing a special concert called “Spirituals to Swing,” showcasing a wide array of black music for a white audience. But by the time Hammond could locate Johnson, he had already passed away.

Johnson had already inspired blues legends and fellow Mississippi natives, Muddy Waters and B.B. King, but it would be decades before his music reached a wider audience.

In 1961, at Hammond’s urging, Columbia released King of the Delta Blues Singers, a 16-track compilation of Johnson’s greatest tunes (he recorded 29 songs in his lifetime). It sparked a blues revival and inspired the likes of Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton.

Dylan later wrote that “there probably would have been hundreds of lines of mine that would have been shut down — that I wouldn’t have felt free or upraised enough to write” had he not heard Johnson’s music.

Johnson’s lyrics spoke of “spirits” and “evil,” and sometimes explicitly mentioned the devil, like his song “Hellhounds On My Trail.”

His songs also contained references to African hoodoo, a spiritual practice of magic that can be traced back to the African ancestry of the black community. In “Come On In My Kitchen,” Johnson mentions a “nation sack,” or a mojo bag worn by hoodoo women to control their lovers:

Oh, she’s gone; I know she won’t come back

I’ve taken the last nickel out of her nation sack

In one tune, he mentions hellhounds and “white powder on the feet,” likely a reference to the black experience of escaping lynching.

Wikimedia CommonsNo one knows exactly where Robert Johnson was buried. This site, officially marked on the Mississippi Blues Trail, is one of three gravesites attributed to him.

Johnson is also credited with adapting the boogie-woogie style of piano playing — where the left-hand plays a bass rhythm while the right-hand plays melodies and riffs — for the guitar.

His “boogie bass” is why so many listeners thought his one guitar sounded like two, and it became a staple of modern blues and rock n’ roll.

His influence even found its way into hard rock with bands like Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones covering and adapting Johnson’s songs.

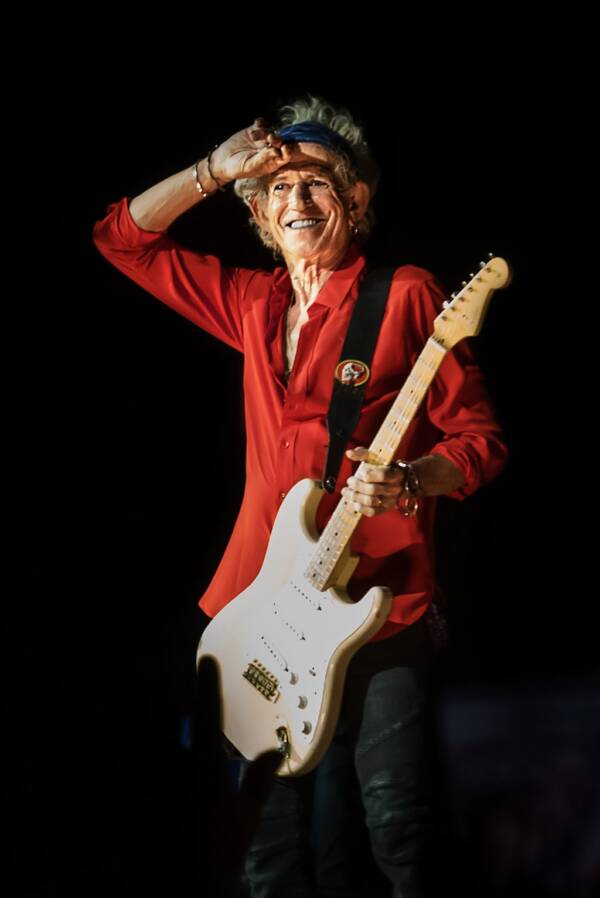

Wikimedia CommonsKeith Richards, another rocker influenced by Robert Johnson’s music, likened the blues king to Bach.

“There’s just something supernatural about Robert,” said Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards, who likened the blues king’s guitar-playing to the work of the classical composer Bach.

But some believe the devil myth only serves to degrade Robert Johnson’s legacy.

“It’s kind of insulting,” explained musician and author Elijah Wald. “It’s kind of implying that, unlike us who do this serious work to understand music, these old black blues guys just went and sold their soul to the devil.”

After reading about Robert Johnson, learn about the legend of the Jersey Devil and its surprising connection to Ben Franklin, and take a look inside the final days of late rocker Kurt Cobain before his suicide.