General Roméo Dallaire's peacekeeping mission in Rwanda ultimately failed when the United Nations ignored his warnings about the coming genocide in early 1994.

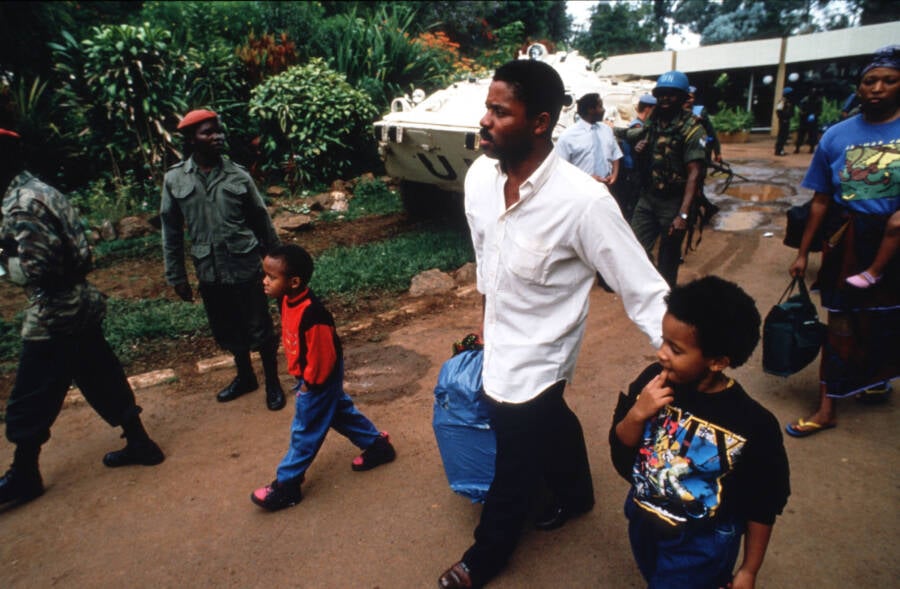

Getty Images/Scott PetersonGeneral Roméo Dallaire shaking hands with Tutsi refugees in May, 1994. With the world’s attention elsewhere and with woefully inadequate resources, Dallaire’s peacekeepers were forced to watch genocide unfold in Rwanda.

“From the moment I first glimpsed its soft, mist-covered mountains, I loved Rwanda,” wrote Roméo Dallaire over a decade after he’d first arrived in the tiny East African country.

In 1993, Dallaire, a general in the Canadian Forces, had been assigned what he thought at first was a prize job: commanding United Nations peacekeeping forces as they sought to protect the fragile ceasefire between the Hutu-led Rwandan government and the mainly Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front.

To an officer in an army that hadn’t seen active service since the Korean War, it was an opportunity to test his years of training and experience while contributing to a worthy cause. But Dallaire’s noble view of the UN’s efforts was rapidly tarnished — first by incessant bureaucratic infighting, and then by the horror of the Rwandan Genocide.

As Dallaire and his men stood by, in full knowledge of what was happening, they kept to intervening and lacked the equipment to protect thousands of civilians. The guilt he felt at being a uniformed witness to the tragedy would haunt him for years afterward.

Roméo Dallaire’s UN Assignment

Wikimedia CommonsRwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana ruled Rwanda as a virtual dictator for 20 years, placing his fellow Hutus in powerful positions and contributing to ethnic tensions in the tiny East African republic.

As a young Francophone soldier in the 1960s, Roméo Dallaire had an intimate knowledge of ethnic tension after seeing the clashes between French and English-speaking Canadians. Years later, in 1993, Dallaire believed that his success in advocating for French-speaking soldiers’ rights and his own deliberate impartiality would prepare him well for the United Nations Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR).

The mission would tide the country’s warring factions over until a broad-based transitional government (BBTG) consisting of representatives from all parties could be established.

By his own admission, Dallaire was hardly an expert in the region or its problems. When he was first informed of his selection in the summer of 1993, he said to his commanding officer, “Rwanda, that’s somewhere in Africa, isn’t it?”

He had no idea that the ethnic conflict between the majority Hutus and the rebel Tutsis they’d persecuted for decades was far from over, and was in fact about to open its most horrifying chapter.

Peace Between The Hutus And Tutsis Collapses

Scott Peterson/Liaison via Getty ImagesWhen the peace talks broke down, thousands of moderate Hutus and Tutsis, like these leaving the renowned Hotel de Milles Collines in Kigali, were left at the mercy of bloodthirsty Hutu supremacists.

The UN mission got off to a rocky start and, in Dallaire’s recollection, slowly got worse. Under his command were just over 2,500 troops, many without adequate supplies or weapons, from a variety of contributing nations.

The best-equipped contingent came from Belgium, a politically sensitive choice since Rwanda had been a Belgian colony until 1962. The total strength fell far short of the 5,500 he’d requested, a sign of international reluctance following the bloody failure of the UN mission in Somalia in 1992.

Political personnel often clashed with UN forces. Chief administration officer Per Hallqvist frequently denied requests for essential supplies, and head of mission Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh seemed less than energetic in mediating disagreements between the RPF and President Juvénal Habyarimana. He even controversially spent Easter weekend with the president in 1994, raising concerns about his impartiality.

Despite all these setbacks, Dallaire remained optimistic. “I was determined,” he later wrote, “to defy the rules, cut the red tape, bend the regulations, and do whatever I had to to achieve our first milestones.”

Yet as the date for installing the BBTG approached, Hutu hardliners in the government had been funneling weapons, cash, and training to the Interahamwe and Impuzamugambi “Hutu Power” militias. A string of mysterious, gruesome murders were reported around the country, with Hutu civilians turning up dead – and officials blaming the RPF.

Dallaire’s Warnings Are Ignored

In the course of investigating these killings, Dallaire’s staff learned of suspicious weapons caches in Kigali, the capital, and Habyarimana’s hometown. Their informants told them that Rwandan Army officers had been assigned to train Hutu supremacist units and to draw up lists of Tutsis in their areas.

The officers themselves suspected that this was being done so they could quickly identify and slaughter Tutsis or, as Hutu militants called them, Inyenzi – “cockroaches.”

When Dallaire suggested searching and seizing these arms caches, Booh-Booh adamantly denied the request. Frustrated, the general sent an urgent fax to UN headquarters in New York, informing them that he believed genocide was now imminent.

Hutu leaders were planning an “anti-Tutsi extermination,” he reported, remarking that one informant had told him that “in 20 minutes his personnel could kill up to 1,000 Tutsis.” Dallaire’s request to intervene was again denied.

Political tensions continued to rise, and on the evening of April 6, 1994, President Habyarimana’s plane was shot down by unknown actors as it flew into Kigali. Both sides accused the other of the assassination, which also took the life of neighboring Burundi’s president.

With the UN, Rwandan military, and RPF forces in turmoil, the hardliners finally struck: armed gangs and government forces began roving through Kigali, hunting and killing moderate politicians, including Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, Habyarimana’s legitimate successor.

By “noon on 7 April, the moderate political leadership of Rwanda was dead or in hiding, the potential for a future moderate government utterly lost,” wrote Dallaire.

Within hours, the killings began in earnest.

The Rwandan Genocide Begins

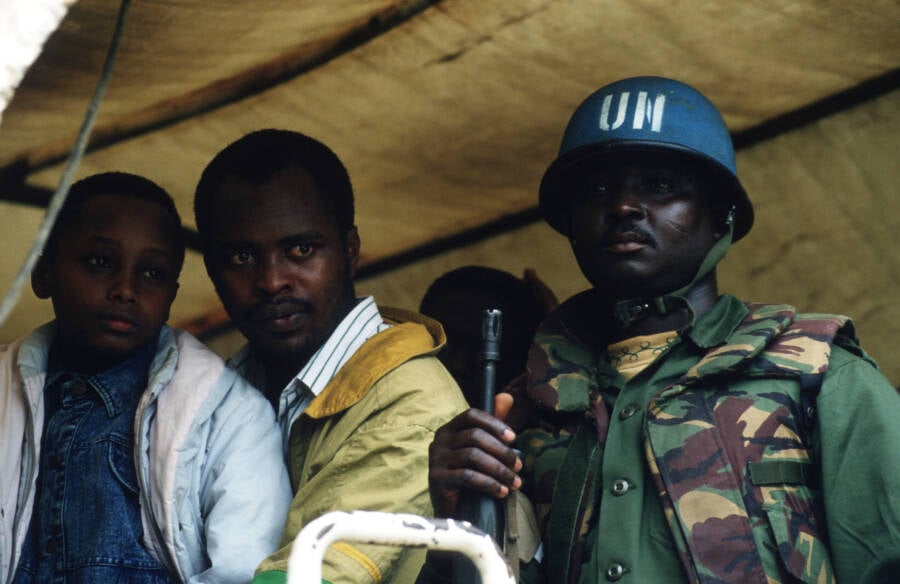

Scott Peterson/Liaison via Getty ImagesPeacekeepers like this Ghanaian soldier selflessly put their lives at risk to get those at risk to safe areas. In the process, 27 UN personnel were killed.

The génocidaires, “those who commit genocide,” fell upon whole neighborhoods, killing indiscriminately with machetes and automatic weapons, many supplied by the French military. Terrified Tutsi civilians gathered at churches and community centers, only to be betrayed by civic and religious leaders and subjected to massacres which claimed tens of thousands of lives.

Among the victims were UNAMIR’s many Rwandan staff. Without their knowledge of the cities and languages, the multinational force was unable to gather intelligence. Panic set in among the troop-contributing nations when 10 Belgian paratroopers who’d been sent to guard Prime Minister Uwilingiyimana turned up dead. The Belgian government promptly withdrew its troops, the best Dallaire had, and advised other governments to do the same.

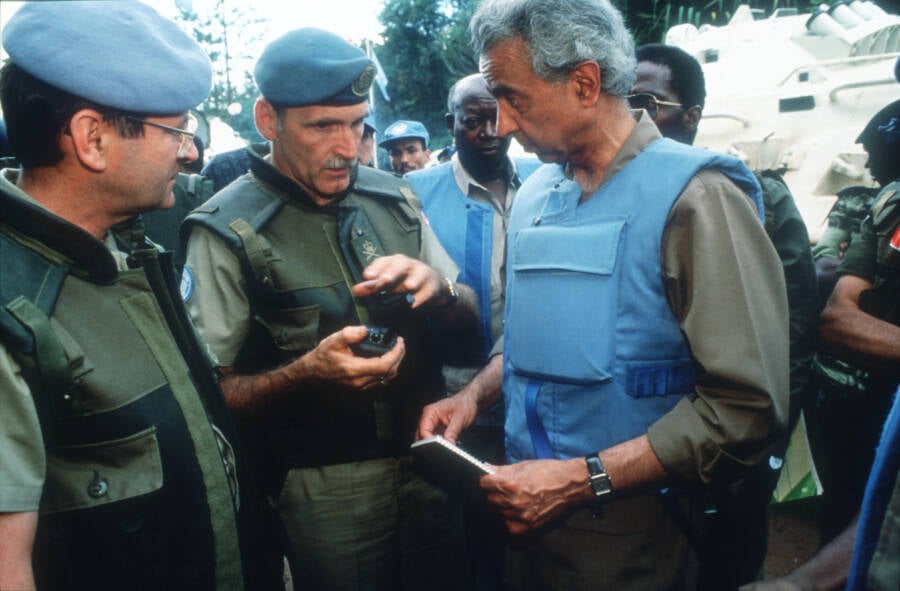

Scott Peterson/Liaison via Getty ImagesAfter the departure of French and Belgian troops, Dallaire and his peacekeepers exhausted themselves trying to restore peace and offer what little help they could to Rwandan civilians.

Even as the remaining UN personnel heroically worked to save as many innocents as possible, UN leaders refused Dallaire the authority to intervene with force, and the United States and the United Kingdom vetoed any request for reinforcements. The killing continued for months against the backdrop of a renewed civil war, and all the peacekeepers could do was watch.

In May 1994, the UN finally sent UNAMIR 5,500 troops along with armored vehicles and desperately needed supplies. After more than three months of indiscriminate killing, the renewed mission — called UNAMIR II — finally had the resources and the authority to protect thousands of vulnerable Rwandans.

The End Of The Killing

Tiggy RidleyThe true cost of the Rwandan genocide may never be known. Estimates of the death toll range from 500,000 to as many as 1.1 million.

The RPF slowly won the war, pushing the génocidaires over the border into Zaire before at last seizing Kigali on July 4, 1994. UNAMIR II would remain in place to safeguard the hard-won peace, but for countless victims, it was too late.

As many as a million people lost their lives in the violence, and tens of thousands were raped, mutilated, and tortured. In apologizing for the UN’s lack of action later, Secretary General Kofi Annan said “The genocide in Rwanda should never, ever have happened. But it did. The international community failed Rwanda, and that must leave us always with a sense of bitter regret and abiding sorrow.”

Roméo Dallaire returned to Canada in August 1994, after nearly a year on African soil. The horrors he’d been forced to play bystander to left deep and lasting scars on him. He turned to alcohol to cope, once being found heavily intoxicated on a Quebec park bench. He even attempted suicide on several occasions.

After a long period of recovery, Dallaire would take a seat in the Canadian Senate and become a tireless advocate of humanitarian aid for victims of ethnic violence and war, and a prolific speaker on his experiences.

“I promised never to let the Rwandan Genocide die,” he later said, “because … I felt it was my duty having witnessed it, and having stayed to witness it, that I had to talk about it and keep it going.”

Now that you know the tragic truth of Roméo Dallaire, find out more about the Rwandan genocide which the world ignored. Then, read about Dr. Wouter Basson, the apartheid-era doctor who concocted a range of genocidal drugs.