Regularly compared to Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, Dr. Wouter Basson was in charge of a top-secret South African biological warfare program behind numerous killings, poisonings, and kidnappings in the 1980s.

“Medicine is my profession; war is my hobby.” While you might not expect words like these to come from the mouth of a cardiologist, Dr. Wouter Basson of South Africa is no ordinary medical practitioner. In fact, when Basson oversaw his government’s top-secret Project Coast during the 1980s, it was his job to develop biological weapons intended to initiate a state-sponsored genocide.

Among other acts of terror, this apartheid-era program worked on “race-specific” bioweapons designed to either pacify, sterilize, or even kill South African’s non-white populations. After apartheid ended in the 1990s, the country’s new leadership declared, “If ever there was a program that truly typified the genocidal programs of the apartheid regime, this was it.”

Despite such atrocities, Basson was only first introduced to the world outside South Africa in a 2001 article by The New Yorker titled “The Poison Keeper.”

“South Africans call him Dr. Death,” the article began. “He’s a decorated former Army brigadier and, in civilian life, an eminent cardiologist, and was the founder and leader of Project Coast, a top-secret chemical and biological warfare program.”

But even after coming to international attention for perpetrating some of the worst of apartheid’s horrors, Dr. Wouter Basson got away with it all.

How Wouter Basson Blossomed In The Apartheid Era

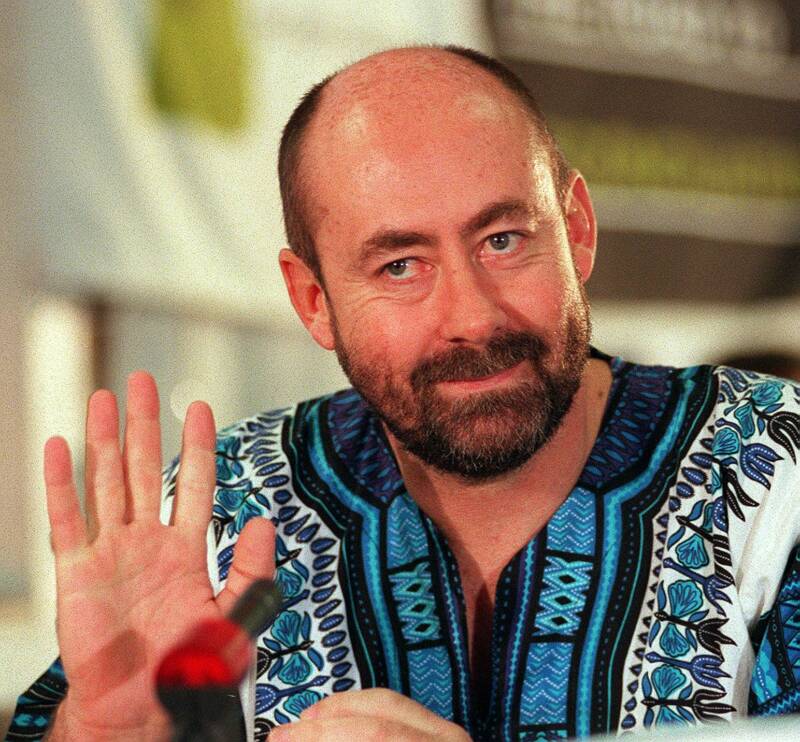

ANNA ZIEMINSKI/AFP via Getty ImagesDr. Wouter Basson waves as he arrives at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearing where victims and perpetrators gathered after the end of apartheid to provide testimony and undergo questioning. 1998.

Apartheid, which is Afrikaans for “apartness,” was a system of political and economic discrimination waged against non-Europeans during the era of white minority rule in South Africa. Introduced in South Africa in 1948, apartheid forced non-white racial groups to live separately from Europeans and attempted to halt any social integration between racial groups.

South African president F.W. de Klerk repealed most apartheid legislation in the early 1990s and a new constitution that enfranchised non-white South Africans went into effect in 1994, formally ending the institutionalized racism. That same year also saw the establishment of a coalition black-majority government that led to Nelson Mandela’s inauguration as the country’s first black president.

But back in the days of apartheid, South Africa was rife with state-sponsored racism — and Wouter Basson was one of the men who put that into practice.

Dr. Wouter Basson was born on July 6, 1950, near Cape Town, South Africa. He graduated medical school from the University of Pretoria in 1974 and joined the South African Defense Force (SADF, the country’s armed forces) in 1975.

By the early 1980s, Dr. Basson had risen to the rank of major and was asked to head the SADF’s top-secret chemical and biological weapons program. He accepted and headed that program, Project Coast, for the next 12 years.

It was here that Wouter Basson would commit his most horrific acts.

State-Sponsored Genocide With Toxic Milk And Whiskey

Foto24/Gallo Images/Getty ImagesBasson at a hearing to determine his fitness to practice medicine on March 26, 2012.

Project Coast was established in 1981 by South Africa’s Ministry of Defense under the direction of then Prime Minister P.W. Botha.

Dr. Wouter Basson headed the operation and recruited some 200 professionals to participate, including high-ranking members of the South African Defense Force, scientists, and doctors. The project was initially presented as a defense-oriented research program meant to protect the country from enemies of the state.

What it really did was manufacture chemical and biological means of neutralizing anti-apartheid activists and preventing non-white populations from growing.

Among his deadly concoctions, Dr. Basson developed anthrax cigarettes, toxic milk, water, and whiskey, and poisoned tools and umbrellas. The idea was that these objects would be distributed in large quantities to the unwitting masses, who would thus be dispatched in secret.

Sometimes, however, Basson’s methods weren’t so secretive. In one operation that killed close to 200 Namibian prisoners of war, the victims were reportedly injected with incapacitating amounts of muscle relaxers and then dumped into the ocean from a helicopter.

But even when Basson’s toxic products weren’t being deployed, they were wreaking havoc in the testing phase alone. In fact, prisoners of war were often used as test subjects and left to die in remote areas.

In one particularly shocking case, Basson was involved in a plot to lace Nelson Mandela’s medication with thallium, “a toxic heavy metal that can permanently impair brain function,” before his release from prison in 1990.

When death wasn’t the objective, the project also focused on synthesizing “race-specific bacterial weapons” to sterilize South Africa’s non-white population.

Dr. Schalk Van Rensburg, the former director of Roodeplaat Research Laboratories, testified before South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (a post-apartheid court-like body that allowed victims and witnesses to testify and perpetrators to undergo questioning or request amnesty for past crimes) that within two weeks of joining up with Project Coast:

“I realized this is not defensive work; this is offensive work. The most frequent instruction we obtained from Doctor Basson…was to develop something with which you could kill an individual which would make his death resemble a natural death, and that something was not to be detectable in a normal forensic laboratory.”

While testimony like this has shed some light on Wouter Basson’s crimes with Project Coast in the 1980s, much of his wrongdoing has surely remained under the veil of apartheid-era secrecy to this day.

Cooking Ecstasy To Pacify Entire Populations

Foto24/Gallo Images/Getty ImagesBasson sits in court during his hearing in 2012.

To grasp the full horror of Project Coast, one need look no further than the words of Wouter Basson himself: “I’m not going to say I did it because I was told to,” he told TimesLive in 2016.

“Some of it I wasn’t. I am not going to hide. It was my job, and whatever I did was not wrong. I am surprised and amazed at the hysteria surrounding my case.”

Indeed, once the project seemingly closed up shop, Basson remained unrepentant — and even channeled his efforts into other ventures.

When Project Coast wrapped up in 1991, Basson moved on to producing drugs like ecstasy (MDMA) and deploy them in ways that would “pacify” non-white populations.

These nonlethal “party” drugs were being synthesized by scientists at a research lab called Delta G, though it was likely just a front company for Project Coast.

Some of these low-level scientists were told they were making rocket fuel, others were told they were creating substances for “crowd control” — but, to be sure, they were involved in Basson’s plot to keep non-whites down with 98 percent pure MDMA.

Nevertheless, Basson maintained that he was only working on methods of “crowd control” during his eventual trials, which finally began under South Africa’s post-apartheid leadership in the 1990s.

“I Was A Soldier”: The Trials Of Wouter Basson

In court, Basson defended his actions and portrayed himself as a foot soldier for the apartheid government. For example, during an interview published the day before his trial began, Bousson said: “My defense in court will be the truth. Whatever I did, I did because it was correct at the time.” He continued:

“What I did was for the good of the country, for things like crowd control. They said doctors shouldn’t get involved, but I was a soldier like any other doing my job. If you want to attack me or associate me with what happened in the army, then you must also look to more than 3,000 other doctors who did national service and willingly fired weapons at people.”

Dr. Basson’s trial began on Oct. 4, 1999, in Pretoria, South Africa. He was initially charged with 67 crimes that included 229 murders, conspiracy to commit murder, drug possession, drug trafficking, embezzlement, fraud, and theft, much of which stemmed from his work as the leader of Project Coast.

Judge Willie Hartzenberg dismissed conspiracy charges related to the deaths of 200 individuals in Namibia after ruling that South African courts lacked the jurisdiction to try Dr. Basson for crimes committed outside the country.

Additionally, the judge dismissed four murder charges in South Africa and 18 months later, he reduced the total number of charges to 46.

After a marathon trial of three years, three months, and 18 days, Judge Hartzenberg ruled that the state fell far short of the standard in proving their case “beyond a reasonable doubt.” He thus dismissed the remaining charges against Dr. Basson. Prosecutors appealed the judgment, but in 2003 South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal refused to grant a new trial.

How exactly Basson got away with all of it remains somewhat baffling to this day. He only called one witness — himself — and often admitted guilt while simply saying he was following others’ leads, but still, he walked free. Some say the judge was on his side, but the case’s outcome nevertheless remains a shocking victory for Basson to this day.

How Basson Escapes Justice Even Today

Though Basson evaded punishment for his Project Coast crimes, he has been periodically embroiled in legal trouble ever since. In 2006, the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) opened a new investigation into him and filed seven charges against him the following year for a smattering of crimes from his Project Coast days.

In January 2012, after a lengthy delay, the HPCSA dismissed two charges and part of a third charge, and a date for a hearing on the remaining four charges was scheduled for March of that year.

After those proceedings finally concluded on Dec. 18, 2013, it seemed as though justice had finally been served when Dr. Basson was found guilty of all four counts of unprofessional conduct.

But on March 27, 2019, Gauteng High Court Judge Sulet Potterill ruled that there was bias on the part of two of the committee members who presided over the HPCSA hearing and that both committee members must recuse themselves from any future disciplinary hearings. The result was that the HPCSA must initiate disciplinary hearings against Dr. Basson from scratch if they intend to continue their review of him.

With the courts on his side once again, it seems like Dr. Death may continue to escape justice again and again.

After this look at Dr. Wouter Basson, read about the Australian genocide against Aboriginals. Then, check out these 35 disturbing photos from the heydey of eugenics.