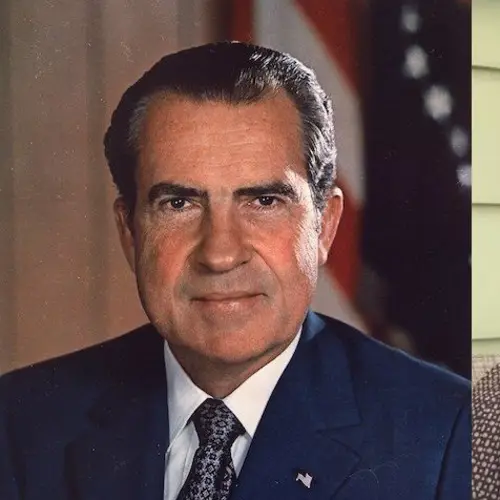

Image Source: CNN/Jim Nowak

Despite all of our worldly excesses, the sandwich is proof that at our core, people are pragmatic. Before the term “sandwich” was coined, this portable food was simply called “meat on bread,” which frankly doesn’t have quite the same ring to it. Hot or cold, savory or sweet, finger-food or foot-long, this layered culinary staple isn’t leaving the world’s collective menu anytime soon. In honor of National Sandwich day, November 3rd, here’s a look at how the history of the sandwich stacks up:

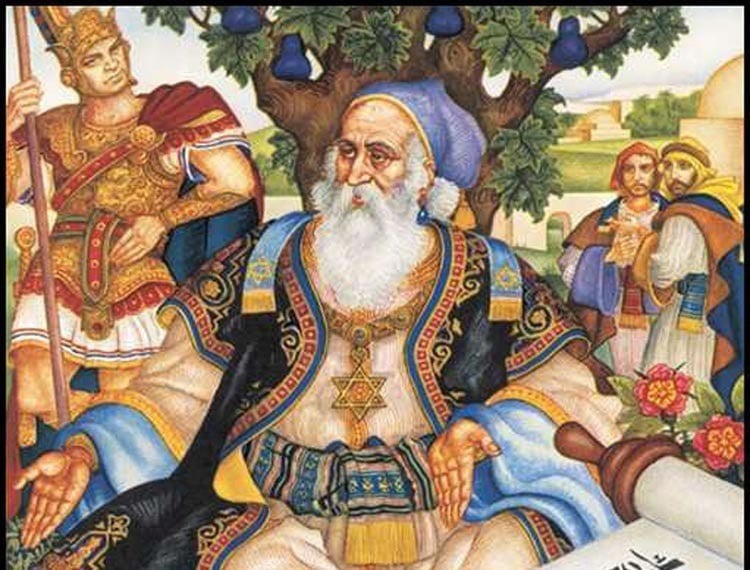

Any way you slice it, the origin of the sandwich is difficult to trace. There are, however, several people throughout ancient history who have been seen with one in their hands (and mouths). The first recorded was Hillel the Elder, a prominent Jewish rabbi who lived around the 1st century, BC. When not crafting the Golden Rule, Hillel is believed to have placed a mixture of chopped nuts, spices, apples, and wine (somehow) between two matzos, which were to be eaten with bitter herbs. It seems that he was the first person to have a sandwich named after him: Hillel’s concoction became so ingrained in the observation of Passover that the food became known as a “Hillel sandwich.”

Hillel the Elder, integrating wine into sandwiches since the 1st century. Image Source: yin and yanglican

During the Middle Ages (between the 6th and 16th centuries A.D.) people ate not from plates, but blocks of stale bread known as trenchers. Among other foods, meats with sauce were piled on top of the trenchers and eaten with the fingers. The trencher would soak up the excess juices due to its thick and absorbent texture, and would be eaten if the diner was still hungry at the end of the meal. Otherwise, the trencher was either thrown away or given to the poor.

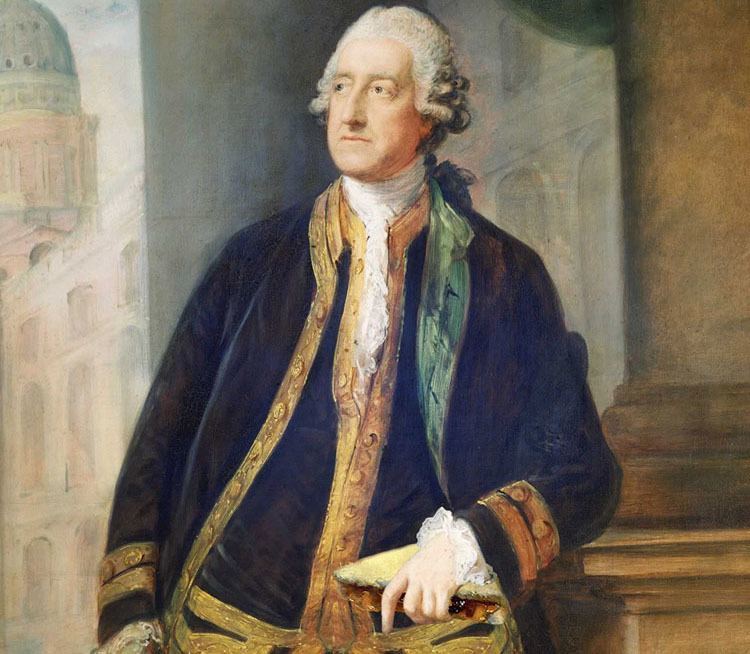

The sandwich didn’t become the sandwich until the 18th century. In the middle of a 24-hour gambling event, the story goes that Fourth Earl of Sandwich John Montagu wanted to be able to continue betting without taking a lunch break. He had previously visited the Mediterranean, where he saw the pita breads and small canapes served by the Greeks and Turks. Montagu instructed an aide to put together a similar meal for him that could be eaten with one hand, leaving him able to continue his gambling spree.

John Montagu, the Earl of Sandwich and gambling enthusiast. Image Source: Delicious History

Though the Montagu didn’t technically invent the sandwich, he gets the credit for making it popular and – in a way – naming it. In the book Sandwich: A Global History, author Bee Wilson writes that people soon began ordering “the same as Sandwich,” which later was shortened to simply ordering a “sandwich.”

Who, then, introduced the sandwich to America? It was likely Englishwoman Elizabeth Leslie, who in her 1850 cookbook Directions for Cookery, In Its Various Branches, suggested *gasp* serving a ham sandwich as a main dish. In her instructions, Leslie writes: “Cut some thin slices of bread very neatly, having slightly buttered them; and, if you choose, spread on a very little mustard. Have ready some very thin slices of cold boiled ham, and lay one between two slices of bread. You may either roll them up, or lay them flat on the plates. They are used at supper or at luncheon.”

Elizabeth Leslie, cookbook author and ham sandwich advocate Image Source: Revolutionary Pie

The final layer in the history of the sandwich is thanks to Otto Rohwedder of Davenport, Iowa, who in the 1920s invented the bread slicing machine. Rohwedder’s invention made life easier for housewives the world over, eventually spawning the phrase “the greatest thing since sliced bread.” Even so, 23 years after this magical contraption made its debut, U.S. Food Administrator Claude Wickard banned the sale of pre-sliced bread. Citing wartime shortages, Wickard thought it required too much packaging. The ban didn’t last long, though: the ban was lifted three months later. Officially, this had to with Wickard overestimating the savings such a ban would produce, but in reality it likely had much to do with harsh public outcry.

Fast forward to the 21st century. Now the sandwich has its official name and its pre-sliced bread. It also has some pretty odd — if not entirely unappetizing — incarnations: