The discovery of a Roman gladiator with Scandinavian DNA raises new questions about migration patterns in early Europe.

Public DomainA 10th-century depiction of Vikings at sea.

In 793 C.E., Vikings attacked a monastery on Lindisfarne, an island off the English coast. This marked the beginning of the Viking Age — and, seemingly, the influx of Scandinavian DNA into Britain. However, a recent study of a Roman gladiator buried in York has challenged this assumption.

Using a new method to study DNA, researchers have determined that the Roman — who was buried between the second and fourth centuries C.E. — was 25 percent Scandinavian. He died hundreds of years before Vikings set foot on English shores, suggesting that the history of early European migration is more complicated than previously thought.

The Roman Gladiator With Scandinavian DNA

According to a study recently published in the journal Nature, researchers made the discovery about the Roman gladiator as part of a larger project to better understand the “genomic history” of Europeans living in the first millennium. They studied 1,500 human genomes, including one of a Roman man who’d been buried in York between the second and fourth centuries C.E.

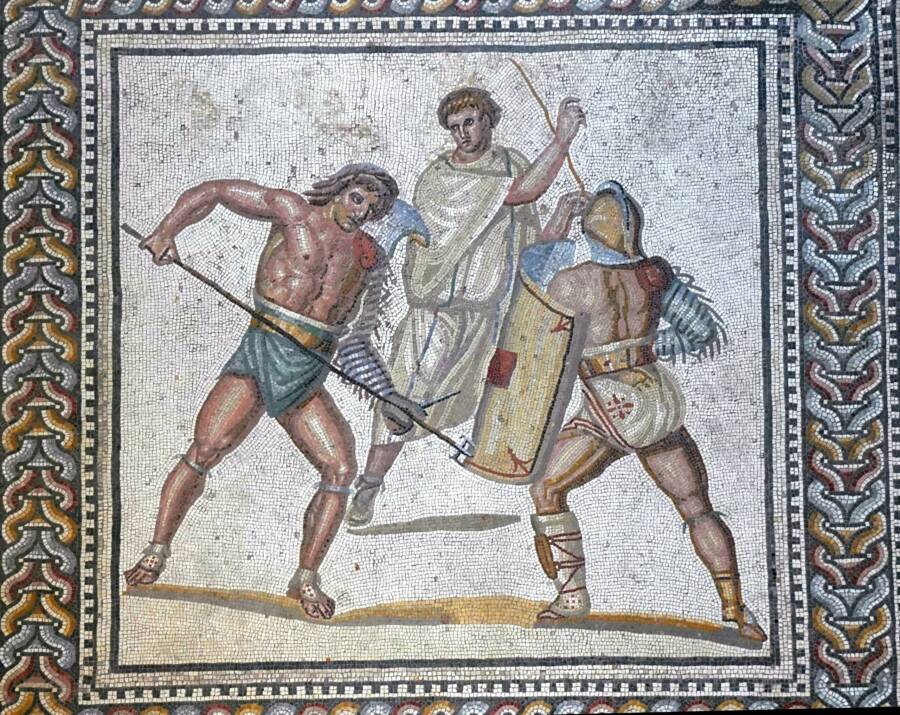

TimeTravelRome/Wikimedia CommonsA third-century depiction of gladiators found in Germany. Though Roman culture spread far and wide, researchers were still surprised to find a gladiator in England with 25 percent Scandinavian DNA.

By applying new methods to his DNA — specifically, the researchers studied relatively recent mutations instead of the overall differences between human genomes — scientists made a surprising find. While the man had been buried at a military cemetery and was assumed to be a soldier or an enslaved gladiator, his DNA was not entirely Roman or British. Instead, the researchers found that he had “25 percent EIA Scandinavian Peninsula-related ancestry.”

Though the ancient Romans were conquerors who pulled people of different nationalities into their ranks, the discovery of Scandinavian DNA in a Roman gladiator was unexpected. As the researchers note in their study, it goes to show that Scandinavians had begun to migrate to Europe far earlier than previously thought — and long before the Vikings arrived.

“This documents that people with Scandinavian-related ancestry already were in Britain before the fifth century C.E., after which there was a substantial influx associated with Anglo-Saxon migrations,” they said.

Indeed, that wasn’t the only surprising part of their study.

How A Study Of Genomic History Revealed New Insights About Early European Migration Patterns

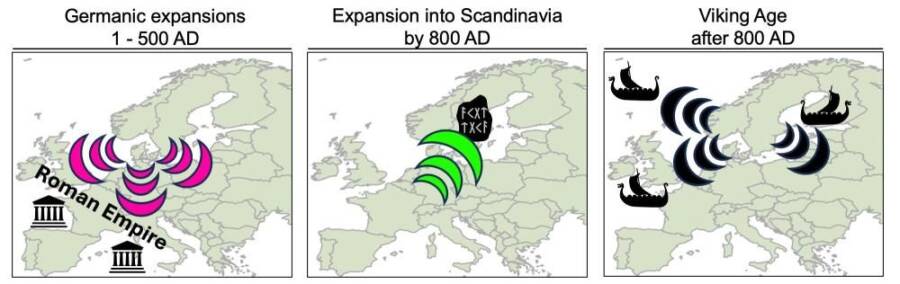

By using their new method of studying DNA, the researchers also identified waves of people migrating south from northern Germany and Scandinavia early in the first millennium. Their DNA was detected in people living as far south as Slovakia and Italy, and one person in southern Europe even had 100 percent Scandinavian ancestry.

Francis Crick InstituteThe migration patterns analyzed in the study.

These groups stayed and mixed with the local population. But then, curiously, the reverse happened. As the study found, people began to migrate into Scandinavia around 800 C.E. At least one person, found buried in Öland, Sweden, had Central European DNA — but showed signs of spending their entire life in Scandinavia.

This suggests that migration trends into Scandinavia represented a significant shift. However, more research is needed to understand what drove people to leave Scandinavia in one wave and then later return.

All in all, the study has painted a more complicated picture of how people left home, moved around Europe, and settled down elsewhere in the first millennium. Though we’ll probably never know the life story of the Roman gladiator discovered in York, for example, his ancestry and burial place is a good representation of the mosaic that was Roman Europe.

After reading about the Roman gladiator buried in England who was found to have Scandinavian DNA, read the stories of some of the most famous gladiators in Roman history. Or, discover the surprising truth about Viking helmets, which most likely did not have horns at all.