How Studying A Fly’s Sex Life Saved Billions Of Dollars

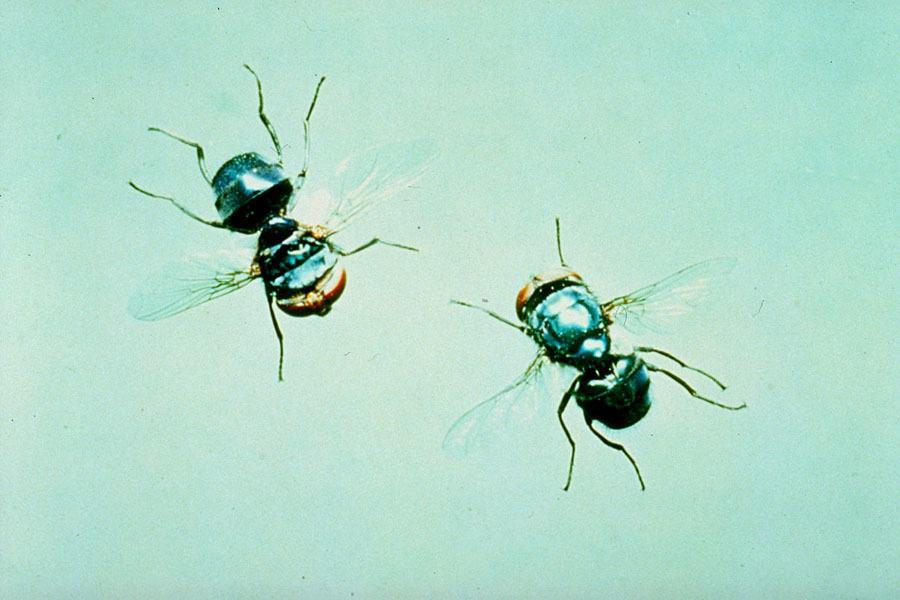

CSIRO/Wikimedia Commons

You’ve probably never heard much about the screwworm fly, and you can thank Edward F. Knipling and Raymond C. Bushland for that. Over the course of several decades, the Department of Agriculture gave Knipling and Bushland $250,000 to research the sex life of the screwworm fly, and the results were truly groundbreaking.

Up until the 1960s, the screwworm fly posed a huge — and costly — problem to livestock. The female fly would lay her eggs in open wounds, which often meant the navel of a just-born calf. The larvae hatch as maggots, and would literally eat the animal alive. Ranchers paid over $200 million in prevention and care for their afflicted livestock, with the flies even killing some people in the southern United States.

Through routine observations, Knipling discovered that the female fly seemed to be monogamous, while males were extremely promiscuous. Armed with this information, Knipling and Bushland developed a theory: If they could sterilize large amounts of male screwworm flies and release them into the wild, the flies’ overall numbers would decrease significantly.

The pair hadn’t any idea how to proceed, but when Knipling came across an article about how nuclear radiation had sterilized fruit flies, an idea was born. Using radioactive cobalt, a by-product of nuclear reactors, Knipling and Bushland were able to sterilize a large population of male flies. By 1966, their sterilization program had eradicated the screwworm fly from the United States and many other countries.

How The Gila Monster Helped Curb Diabetes’ Most Debilitating Effects

Wikimedia Commons

One scientist’s interest in reptiles may be responsible for your diabetic grandma’s relatively pain-free life.

In the early 1980s, Dr. John Eng (working under Nobel Prize winner Rosalyn S. Yalow) was investigating small mammal hormones in order to test a method of discovering new hormones. Eng, also a practicing physician, was highly aware of the debilitating effects diabetes had on his patients.

Eng shifted his research from mammals to reptiles after reading about the effects of snake and lizard venom on the pancreas, which maintains the body’s blood sugar balance. In 1992, Eng isolated a compound from gila monster venom, which he named Exendin-4.

This compound stimulates insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, producing a steady, normal glucose level. Exendin greatly improved upon the insulin shot, which came with the risk of glucose levels going too low — to the point that one could lose consciousness in attempting to help themselves.

Eng’s discovery garnered him the attention of a small biotechnology company. That company, Amylin Pharmaceuticals, produced the drug exenatide from the new compound. The Food and Drug Administration approved the drug in 2005, and it can now be found in the medication known as Byetta.

Prescribed to millions of people with diabetes, the drug improves blood sugar levels and often prevents the disease’s more severe complications from arising. All with a little help from the gila monster.