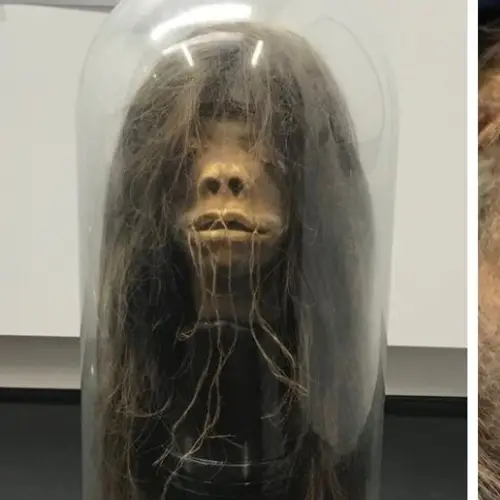

For centuries, the Jivaroan people of South America severed and shrank the heads of their enemies for rituals and trophies — and later for trade.

Head-shrinking seems like a tall tale that explorers would make up about a remote tribe. However, the practice of making shrunken heads is very real, especially in the forests of Peru and Ecuador. There, the Indigenous Jivaroan people practiced this macabre tradition for centuries.

When Europeans learned about the practice of shrinking heads in the 19th century, they were fascinated. Soon, many Westerners wanted to buy the shrunken heads to put in museums and sell as tourist trinkets.

Before long, a gruesome new economy arose.

The History Of Shrunken Heads

In the northwest regions of the Amazon rainforests, the Jivaroan people began shrinking heads of dead people centuries ago. But this tradition wasn't meant to preserve their spirits or protect them in the afterlife.

Instead, the Jivaro shrunk the heads of their enemies — as a defensive tactic. This practice grew out of their beliefs about angry spirits.

According to the International Journal of Legal Medicine, the Jivaroan people started creating shrunken heads out of fear that, after killing someone in battle or during a raid, the person's vengeful spirit (or muisak) would come back and kill them. To prevent any such paranormal activities, the Jivaro would shrink the heads of their enemies they'd just killed.

By shrinking the heads, angry souls could not haunt their killers after death. Instead, they would be trapped inside the heads, according to the Jivaro's beliefs. Each of these shrunken heads was known as a tsantsa.

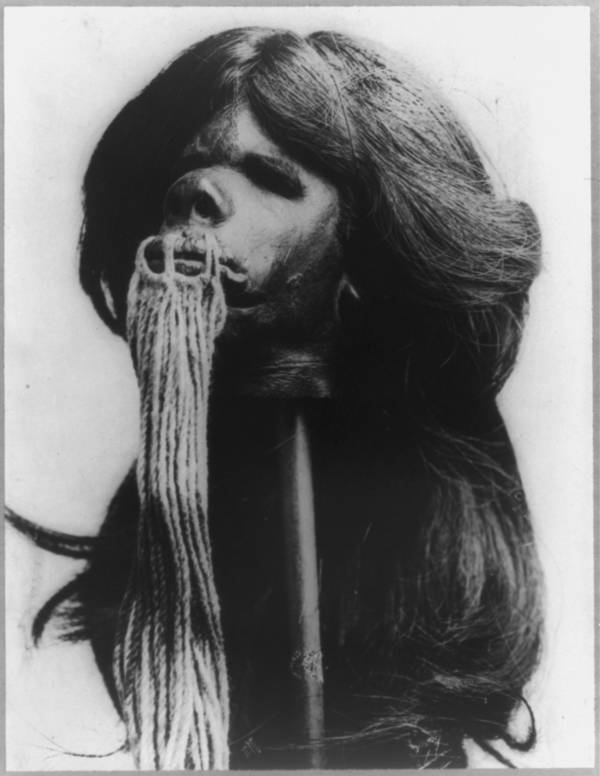

National Museum of the American IndianThe Jivaroan people sometimes made shrunken heads from sloths, since they believed that these jungle animals had souls that were similar to those of human warriors.

Aside from using tsantsas to prevent vengeance from beyond the grave, the Jivaro would also create shrunken heads as trophies of revenge against tribes that had wronged their ancestors. These trophies were often worn on necklaces. Thus, a tsantsa was a not-so-subtle warning to others not to mess with the Jivaro, lest their heads also end up on a necklace.

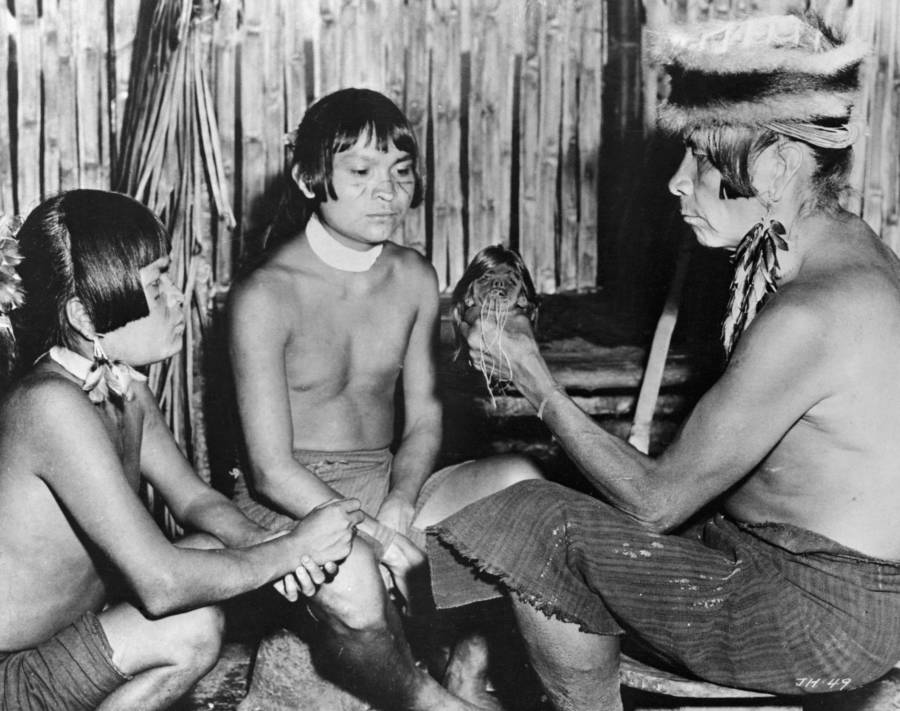

While most tsantsas were part of spiritual rituals, the Jivaro sometimes used the shrinking process in other ways. When boys entered manhood, they might learn how to shrink heads as a rite of passage.

The Jivaro also sometimes shrunk the heads of sloths. The sloth was seen as the only jungle creature with a vengeful soul. If a warrior was unable to take an enemy's head, he could shrink a sloth's head as a replacement.

When European explorers first visited the remote rainforest tribes in the 19th century, they were surprised to discover miniature human heads. Although several different groups of people around the world had headhunters, the Jivaroan people stood out for shrinking the heads of the enemies they killed — especially since they did so in such a unique manner.

How Shrunken Heads Were Made

The actual process of creating these shrunken heads is almost as unusual as the final result of the tsantsas itself.

After the enemy tribesmen were decapitated, the Jivaro took their heads and carefully skinned them. The skin from the heads was then tossed into a pot and boiled for as long as two hours. By the time the boiling was done, each head would be about one-third the size that it had originally been.

According to ZME Science, the Jivaroan people sometimes turned the skin inside out after it was removed from the pot, to get rid of any excess flesh.

The eyelids were then sewn shut and the mouths were sealed, sometimes with wooden pegs. Hot stones and sand would also be inserted into the head, to make it contract even more and become smaller.

Once the head had contracted enough, more hot stones would be applied to the outside to heat the face enough to seal its shape. When the face was finished, the head would be rolled in charcoal ash and hung over a fire to harden. This was also done to keep the dead person's muisak inside the head and prevent it from doing any haunting in the afterlife. Finally, after all that, you would have a finished tsantsa to put on display.

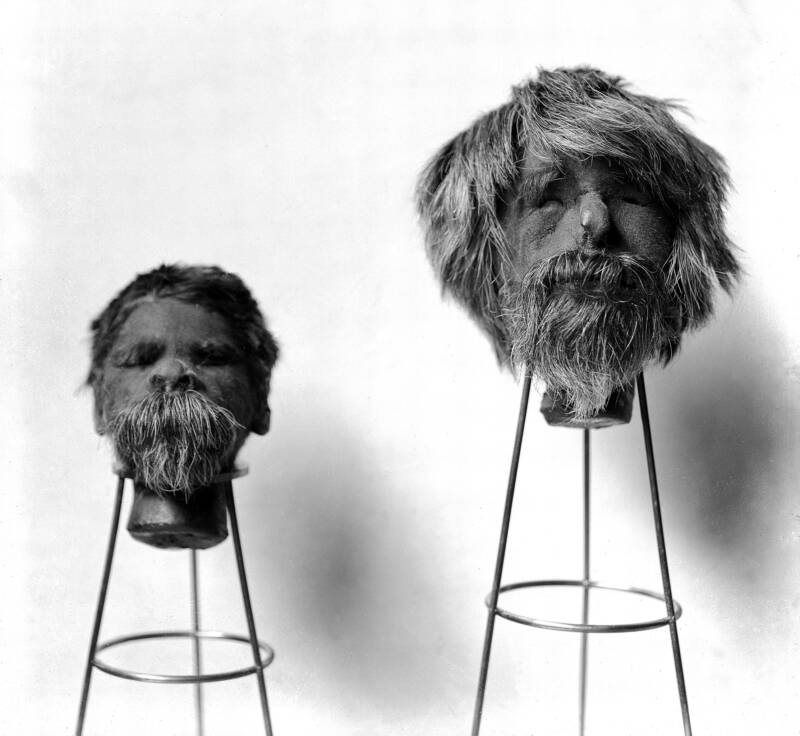

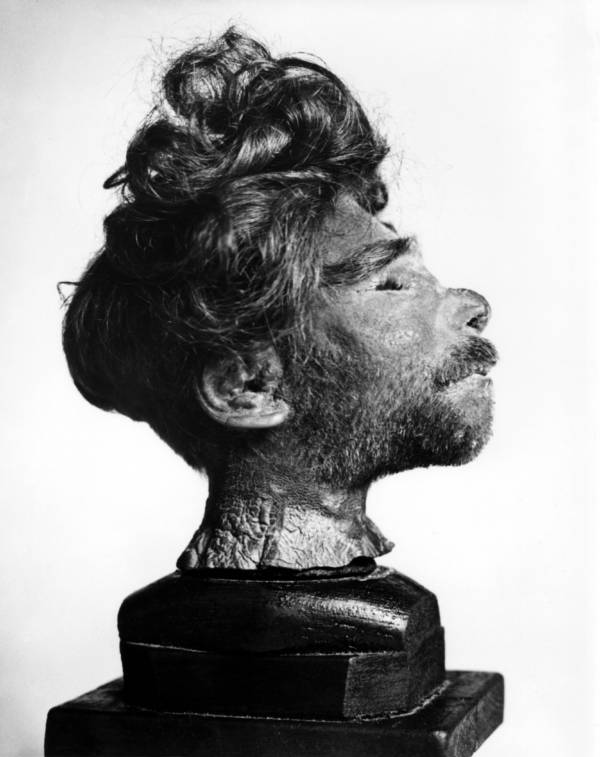

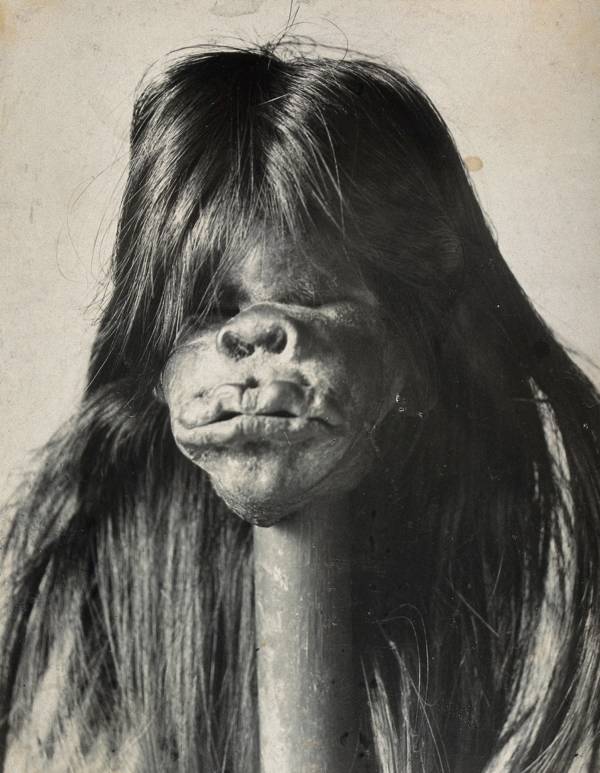

Wellcome CollectionThe head of a Huambisa tribesman, who was killed in battle in Peru. 1899.

The Jivaro primarily made tsantsas from the heads of men, as most enemy warriors they encountered were male. They also believed that men were the most likely to seek paranormal revenge. Often, an attack on a neighboring village would raise fears that angry spirits might plague the attackers. So Jivaro warriors beheaded the dead and carried their heads home.

Making a tsantsa required skill, which began with the process of removing the head. Sloppy work made it difficult to properly shrink the head. The Jivaro would sever the head close to the base of the neck, aiming for a V-shaped cut right above the clavicles. In order to remove the skin from the skull without causing damage, warriors would submerge the head in a river.

And of course, precision was necessary when it came to skinning the head and shrinking it down. In all, the entire process could take up to three days. At the end, the tsantsa would be around a fourth of its original size.

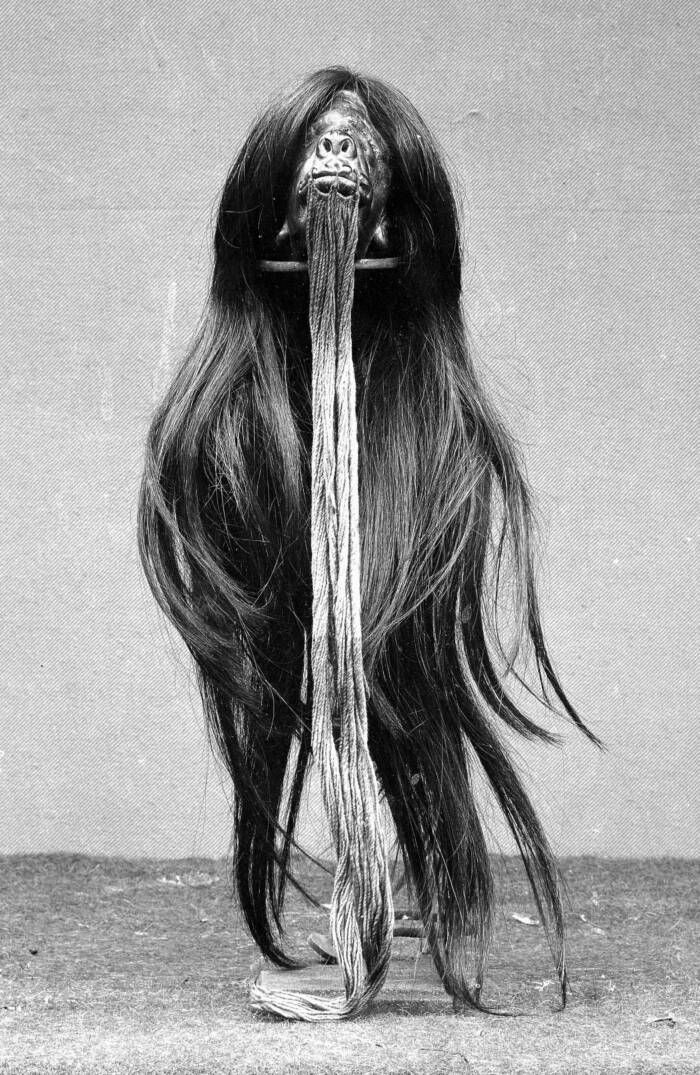

While the process shrunk the head, the victim's hair remained the same length. That led to shrunken heads that seemingly had extremely long hair.

A Surprising Market For Tsantsas

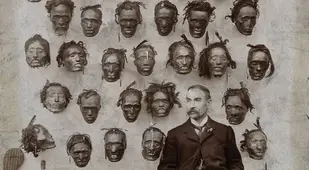

When Europeans first found out about these shrunken heads in the 19th century, stories about them spread like wildfire. Before long, these human remains became extremely desirable collectible items among Westerners.

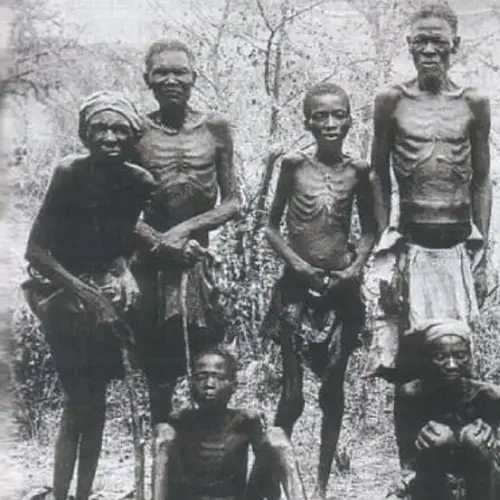

The Jivaro began to trade the heads with Europeans for guns and knives, but demand was so high (at one point, a single head could cost $300 in today's currency) that the Jivaro began to kill more people than they usually did in order to provide more heads and continue trading.

Once, shrinking heads had been part of the Jivaroan spiritual system. But by the late 1800s, tsantsas had become a key part of the Jivaro economy, and many warriors were willing to do whatever it took to create more.

Though in the past, most tsantsas were made from deceased male warriors, headhunters began targeting women and children to meet European demand, according to the Pitt Rivers Museum. By 1895, raiders were regularly seizing women and children to shrink their heads. Along the edges of Jivaroan land, headhunters also targeted non-Indigenous people.

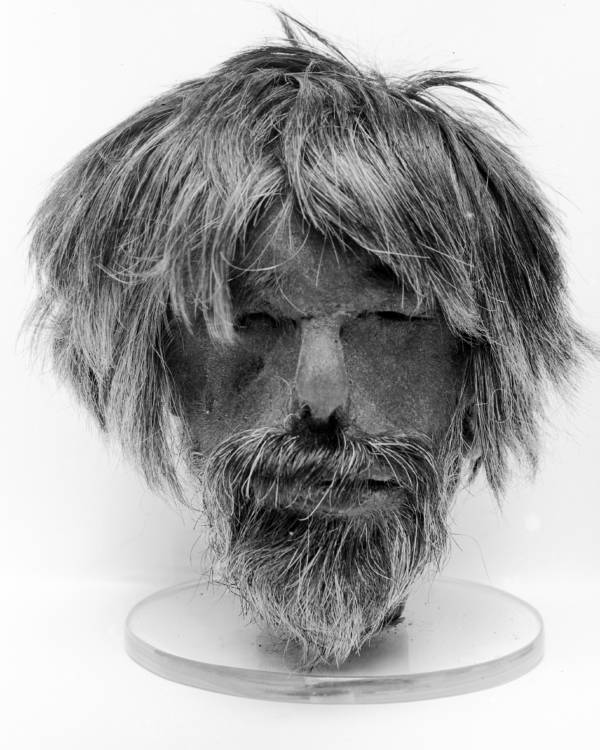

Ecuador, Peru, and Brazil eventually outlawed the practice of shrinking heads for tourist trade. But the practice continued. Headhunters also targeted animals. After the boiling process, the heads of monkeys and sloths could sometimes be confused for human heads. Traders also rummaged through the morgues, looking for unattended heads they could sell.

Because of this, about 80 percent of shrunken heads in museums and private collections are believed to be counterfeit. As for the real ones, many now believe they should be returned to the place where they came from.

Changing Perspectives On Shrunken Heads

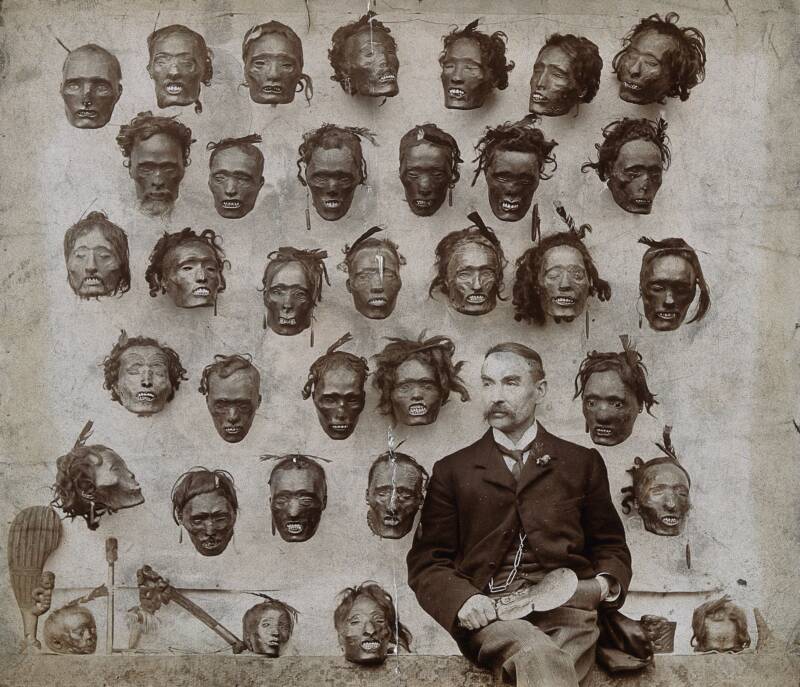

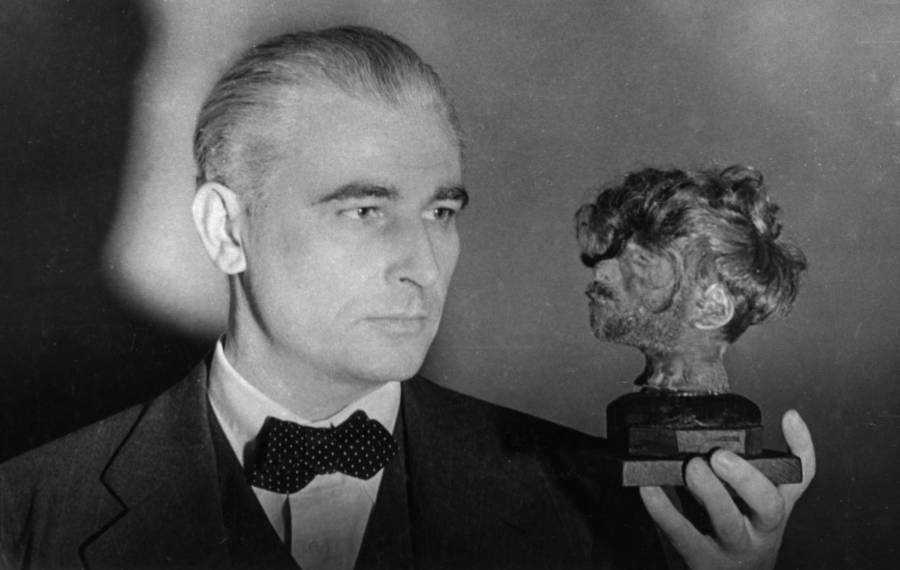

Wellcome ImagesThe Wellcome Historical Medical Museum in London had an exhibit in the mid-20th century called the "Hall of Primitive Medicine," which featured a number of shrunken heads.

You'd think that a shrunken head trade would be stopped immediately, but it wasn't until the 1930s that buying a tsantsa was outlawed in South America.

The Jivaroan method of shrinking heads also inspired others to replicate this practice. And the counterfeiters weren't always Indigenous people.

Shrunken heads were even discovered in the Nazi concentration camp of Buchenwald after World War II — and they were believed to have been the heads of Russian POWs. Since the Nazis were known for performing horrific experiments on victims in concentration camps, many thought the shrunken heads were yet another example of Nazi atrocities. However, other sources state that the heads in question may have originated from South America.

Many Jivaroan shrunken heads ended up in Western museums during the early and mid-20th century. Exhibits prominently featured the heads as evidence of the "primitive" people of the Amazon. The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford labeled one exhibit "Treatment of Dead Enemies." The exhibit also contained other human remains from around the world. By the 1990s, the Smithsonian had a collection of more than 20 tsantsas in their collection. (However, an audit indicated that just five of those heads were authentic.)

But as a new millennium approached, many scholars began to reconsider whether these heads — once part of an Indigenous spiritual tradition — should be on display at all. In 1999, the National Museum of the American Indian became the first museum to send its tsantsas back to the Jivaro.

Eventually, other museums followed that example. In 2020, the Pitt Rivers Museum removed its tsantsas because the display encouraged racist beliefs among visitors, who were often heard describing the Jivaro as savages.

The practice of making new shrunken heads is all but nonexistent today. But the process of repairing the harm caused by the tsantsas trade continues — especially since black market dealers are still willing to sell them today.

After this look at shrunken heads, discover some of the most extreme body modification practices around the world. Then, read about witch doctors.