Like many Christian sects, Tsarist Russia's Skoptsy believed sex was a sin. Unlike most sects, they also believed that the only way to get to heaven was to cut off their own genitals.

Russia Beyond Skoptsy’s ability to unite the isolated masses of Russia made the sect stick, and surviving long after the death of its founding fathers.

In their devout faith, followers of Tsarist Russia’s Skoptsy sect could be compared to Orthodox Christians. They both believed in saints and sinners, heaven and hell, and that Jesus Christ died on the cross to give the world salvation. But only the Skoptsy believed Jesus was also castrated.

This was really how Jesus absolved the world, according to Skoptsy founder Kondraty Selivanov. So fiery was his passion that soon enough, his sect amassed thousands of members — up to 1 million by some estimates. They were fervent proselytizers, reportedly coercing children and prisoners to join them in order for their ranks to reach the magic number of 144,000 — at which point Jesus Christ would return.

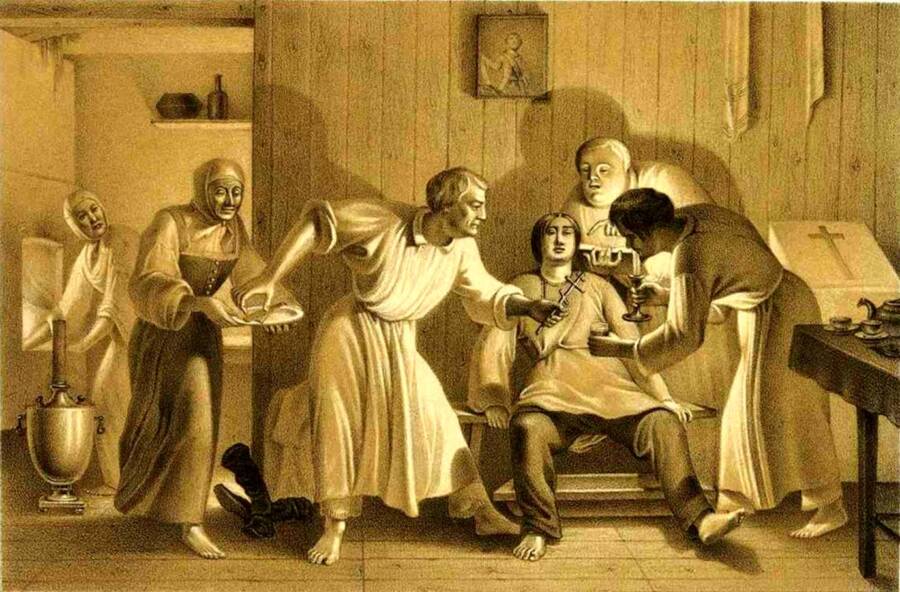

In a ritual ceremony reportedly called “the seal,” men and women removed parts of their sexual organs to seal their faith in God and live in true imitation of Christ on the cross.

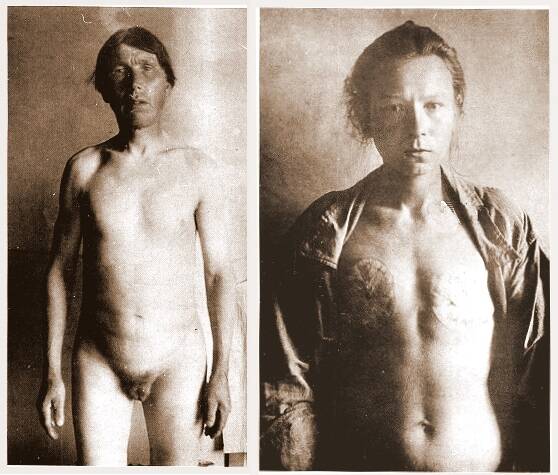

Men who opted for the “lesser seal” removed their scrotums and testes, while those who took the “great seal” removed it all — including the penis. It often happened in one swift motion; as one medical study put it, “the operator seized the parts to be removed with one hand and struck them off with the other.” Women, in turn, had their breasts cut off and their genitalia mutilated.

These dismemberments were called “fiery baptisms,” perhaps because they were often performed with red-hot iron rods.

radeniyeSkoptsy men would cut off their genitals, while the women would cut off their breasts.

Although the Skoptsy’s religious doctrine was initially written off as the ravings of a madman, its founders’ ability to lead new members into losing their genitals was genius.

How Christianity’s History Of Genital Mutilation Birthed The Skoptsy

Self-castration is nothing new; it’s a well-documented practice in Christianity’s long, complicated history. Reportedly, the passage that gave birth to the Skoptsy movement came from the Gospel of Matthew, the first book of the New Testament and one of the bible’s three synoptic gospels.

It reads, “There are castrates who were castrated by others and there are castrates who castrated themselves for the Kingdom of God.”

When taken at face value, the passage makes the case for self-castration. But the Skoptsy were not the only religious sect hanging on every word of the Christian Gospel.

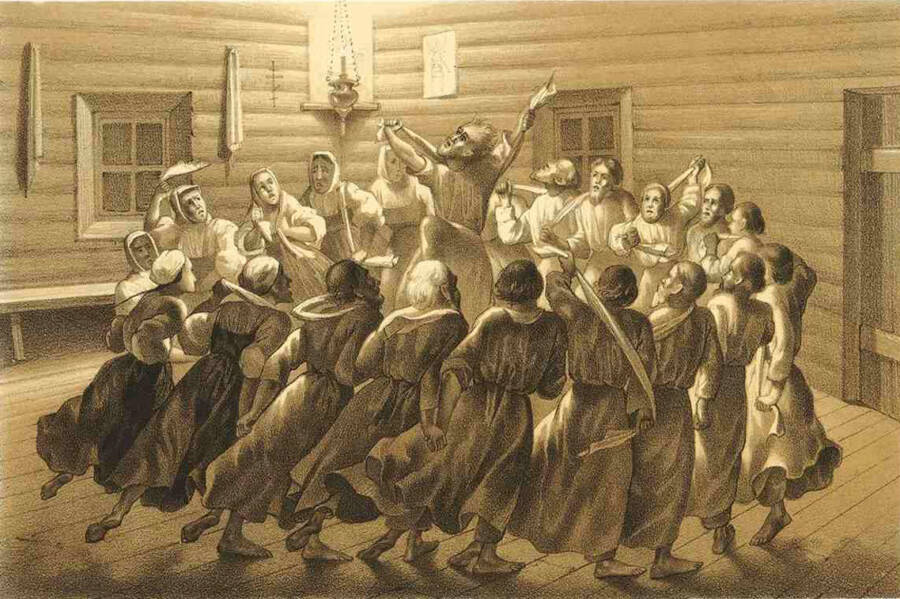

Most Christian Orthodox sects adopted ascetic principles such as refusal to eat meat, drink, swear and have sex from the mystical sect of the Khristovshchina or Khlysty.

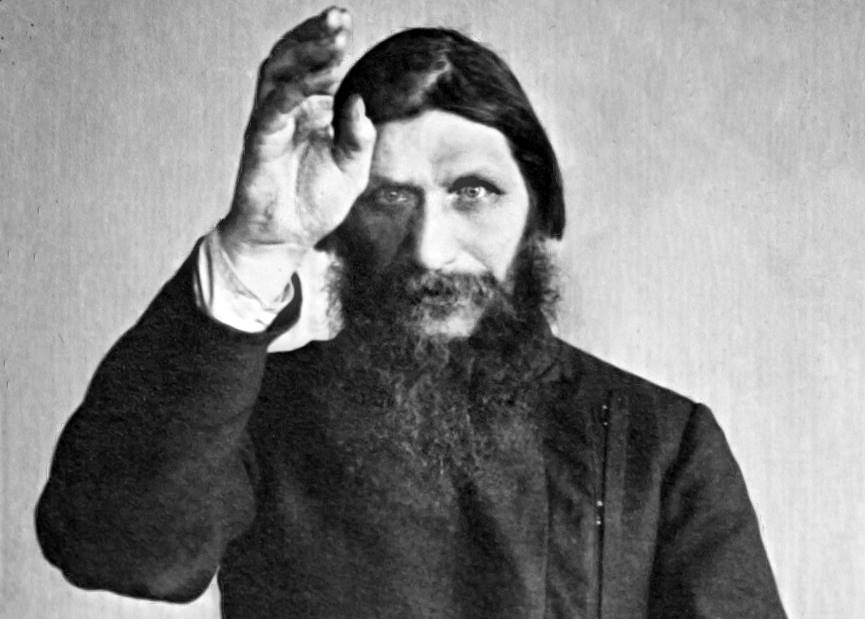

Wikimedia CommonsGrigori Rasputin was accused of being a Khlyst, a sect that broke off from the Russian Orthodox Church and which shares some religious tenets with the Skoptsy.

Known as the “Old Believers,” the Khlysty sect emerged in the first half of the 18th century when they separated from the Orthodox Church in a refusal to accept reforms.

Adopting most ascetic practices from the Khlysty, the Skoptsy took things further with castration — all in one extreme attempt to achieve a higher level of purity and connection with God.

Skoptsy’s Early Followers In Russia And Its Father

The first Skoptsy date back to the mid-1700s, in a sparsely populated area of Russia hundreds of miles from Moscow. The sect’s three original members believed that if they could escape the sin of lust, they’d live forever. So they castrated themselves and a few dozen others.

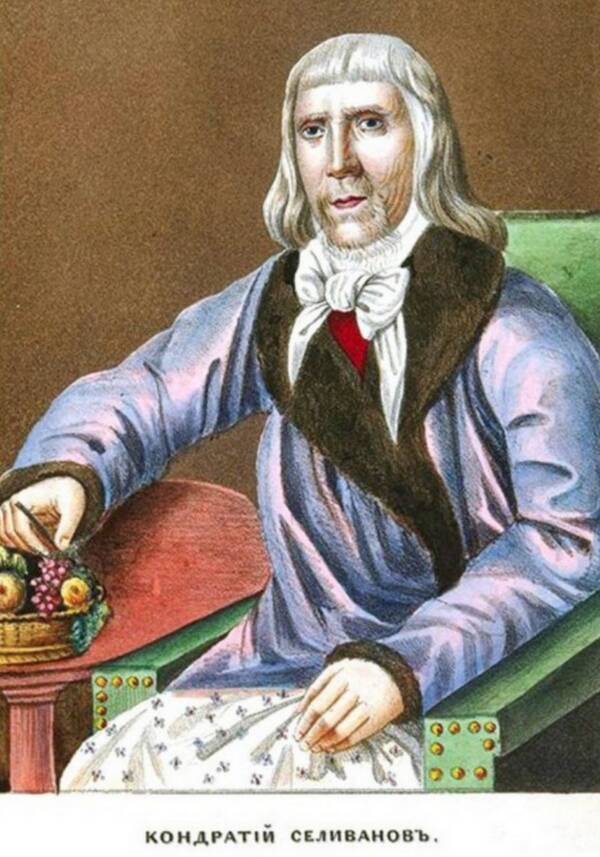

ribalych.ruKontrady Selivanov came to be the Skoptsy’s main leader and spokesperson.

In 1772, the clan was banished to Siberia — but they only grew stronger. About 20 years later, Kontrady Selivanov returned as an “authoritative mystic,” writes Russia Beyond, “having converted dozens of people to his faith.”

Over many exiles, Selivanov returned and reinvented himself with increasingly wild proclamations. His presence in and around Russia’s common folk reached a mythological level, and each time he returned from exile he brought more Skoptsy followers who were turned in their isolation.

In 1817, officials arrested Selivanov and sent him to a monastery for madmen. By then, he had enough loyal followers to think of himself as the second coming of Christ — which he reportedly did with his public veneration, up until his death in isolation in 1832.

But the death of its leader and main spokesperson didn’t stop the Skoptsy movement from spreading across Russia. By the second half of the 19th century, the Skoptsy sect had moved from the fringes of society and integrated itself into everyday Russian life.

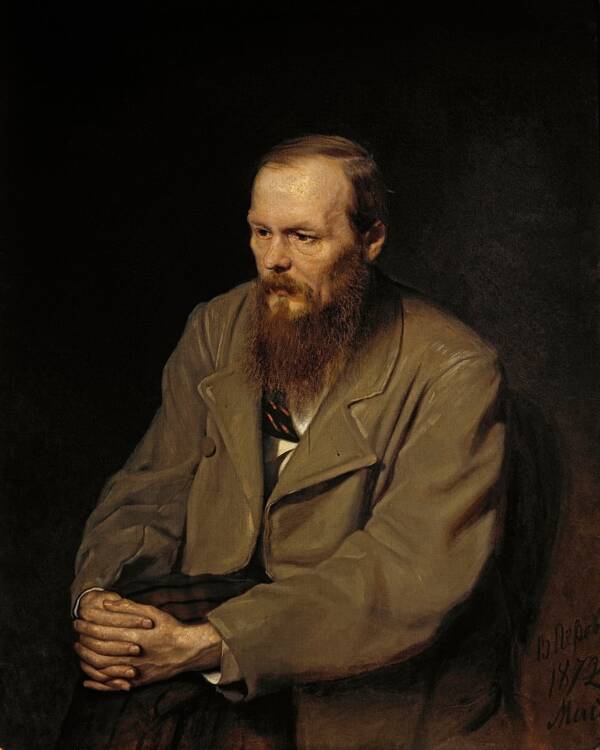

In his book, The Idiot, for instance, Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote about “the skopets who holds the shop generally lodges upstairs.”

The word skoptsy is in reference to the outdated Russian term oskopit, which means “to castrate.” Skoptsy followers preferred to call themselves by nicknames such as God’s Lambs or White Doves, but ultimately adopted the epithet as their true name.

Wikimedia CommonsIn a ritual ceremony called “the seal,” men and women removed their sexual organs to seal their faith in God and live in true imitation of Jesus Christ on the cross.

Among the illiterate provincial peasantry and merchant houses of St. Petersburg, Skoptsy was one of many sectarian offshoots in the larger Christianity movement during the Russian Empire. But the Skoptsy’s ability to unite the isolated masses made the sect stick, surviving long after the death of its founding fathers.

From Heaven To Hethens, Modern Day Skoptsy

Many historians believe the secret to Skoptsy’s success was its ideological purity. As people thought Orthodox Christianity to be too bureaucratic and degrading in structure, they went in search of a truer faith in Christian offshoots.

Then there was the promise of eternal life. With the belief that sex was a sin, peasants castrated themselves because they believed it was the only way to reach heaven.

More members helped the Skoptsy gain more power and influence, which they used to convert more people and gain wealth. They bought peasants, provided shelter for orphans and supported the unfortunate, which further increased their numbers.

WikipediaIn his book The Idiot, Fyodor Dostoevsky described Skoptsy tenants in a boarding house.

Initially, the Russian government mostly “closed its eyes” to religious sects. Because they were mostly located in rural areas, they were difficult to find and control.

However, Stalin’s rule during the 1930s brought the Skoptsy to a fiery end with repression and arrests. They were deemed “un-Soviet.” The last known Skoptsy castration happened in 1927, and by 1930 their numbers had dwindled to between 1,000 and 2,000.

The Skoptsy sect is believed to be mostly extinct today, but there is a modern iteration of its beliefs in the “anti-sexuals” movement. Self-castration is not a requirement, but according to one movement activist, it is welcomed.

After learning about the unorthodox Russian sect of Skoptsy, check out the seven strangest religious rituals and beliefs from around the world. Then, read about the “Mad Monk” Grigori Rasputin and his dramatic death.