Dr. Richard Madgwick's research indicated that the pigs used for these ancient feasts weren't locally raised, suggesting attendees transported the animals for hundreds of miles as a contribution.

Wikimedia CommonsStonehenge, 2008.

Stonehenge has fascinated mankind for centuries as to what function the UNESCO World Heritage Site had in ancient societies. Human bone deposits found at Stonehenge suggested the group of obelisks served as an ancient burial site, but a new study points toward the Wiltshire, England site having filled a more celebratory need as well.

According to a Cardiff University-led study, recently uncovered and examined the bones of 131 pigs suggest the four Neolithic sites — Durrington Walls, Marden, Mount Pleasant, and West Kennet Palisades Enclosure — were home to the earliest celebratory feasts in Britain.

Led by Dr. Richard Madgwick of Cardiff University’s School of History, Archaeology and Religion, the evidence indicates that people and animals across the United Kingdom traveled hundreds of miles for these early food-centric rituals and brought their own animals.

“This study demonstrates a scale of movement and level of social complexity not previously appreciated,” said Madgwick.

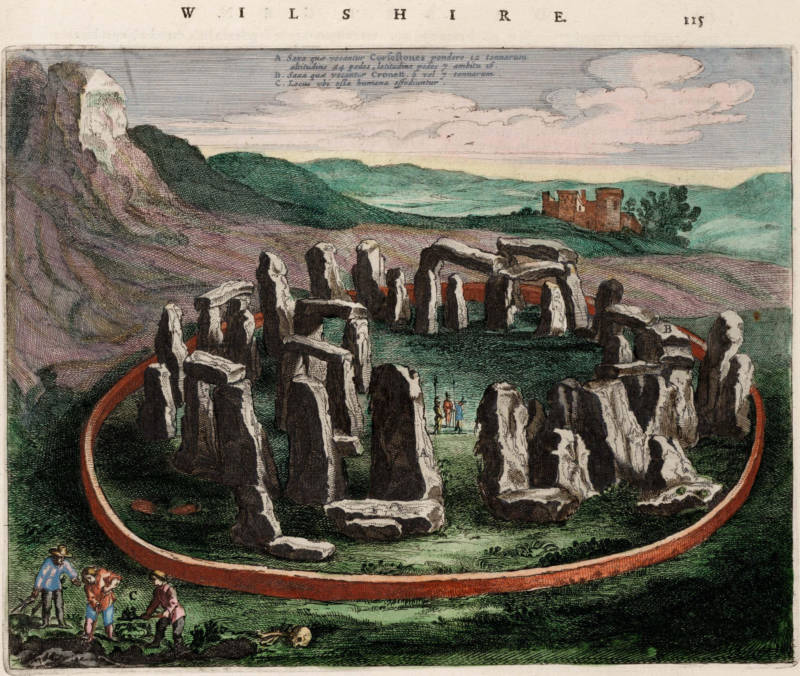

Wikimedia CommonsA 17th-century depiction of Stonehenge Atlas van Loon (1645).

While the excavation itself and subsequent dating of the discovered bones served to reveal that early Britons did, indeed, use the location as a place to feast, it was the study’s multi-isotope analysis process that clarified the migratory aspects of the research: the consumed animals were not raised locally.

Madgwick’s research, published in the Science Advances journal, suggests the pigs had come from all corners of the region including Scotland, northeast England, West Wales, and other areas across the British Isles.

The Cardiff University professor proposed that this meant it was important for attendees to contribute livestock for the feast as a sign of goodwill.

“These gatherings could be seen as the first united cultural events of our island, with people from all corners of Britain descending on the areas around Stonehenge to feast on food that had been specially reared and transported from their homes,” said Madgwick.

Though some human remains have been found at the site, their scarcity left archaeologists and research teams without enough resources to properly study who died there and where they came from. Since pigs were the most popular animal for these feasts, however, their bone analysis filled those gaps — and became more informative than their human counterparts.

“Arguably the most startling finding is the efforts that participants invested in contributing pigs that they themselves had raised,” Madwick said. “Procuring them in the vicinity of the feasting sites would have been relatively easy.”

Cardiff UniversityDr. Richard Madgwick weighing pig remains for the isotopic analysis.

Isotope analysis can essentially identify chemical signals from the food and water an animal has consumed. This allowed Madgwick’s team to make informed estimates as to the locations of where these pigs were raised.

Since the strontium-87 isotope is more common in relation to strontium-86 in the Scottish Highlands and Wales than it is in south-central England, for instance, Madwick’s team was able to garner a clear picture of the migration patterns at work. According to IFL Science, animals reflect these ratios in their bones.

In terms of Stonehenge studies, this is one of the most comprehensive projects regarding mobility and migration of the site during that era.

“Pigs are not nearly as well-suited to movement over distance as cattle and transporting them, either slaughtered or on the hoof, over hundreds or even tens of kilometers, would have required a monumental effort,” said Madgwick.

“This suggests that prescribed contributions were required and that rules dictated that offered pigs must be raised by the feasting participants, accompanying them on their journey, rather than being acquired locally.”

After learning about the study suggesting Stonehenge served as one of the earliest large-scale feast locations in Britain, read about Gobekli Tepe — the oldest temple in the world. Then, learn about a study suggesting the earliest humans came from Europe instead of Africa.