Believed to date back at least 10,000 years, trepanation involves drilling a hole into a person's skull and exposing the membrane surrounding their brain.

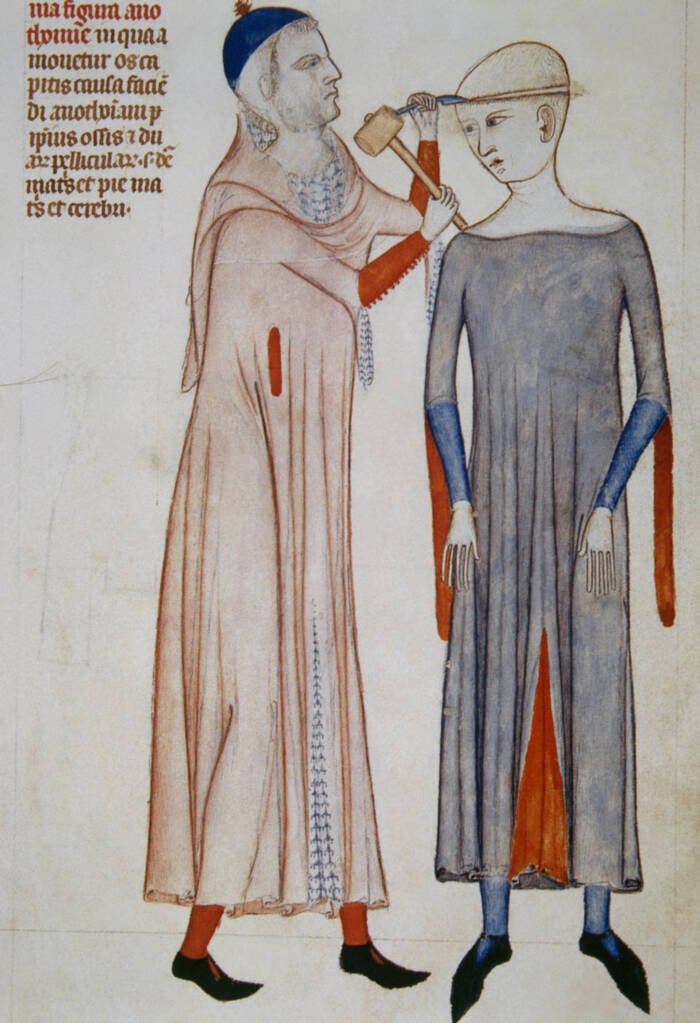

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of trepanation by Early Netherlandish artist Hieronymus Bosch.

Despite what the gory illustrations may suggest, the act of drilling holes into a person’s head was not a medieval torture method. This act, called trepanation, is actually a millennia-old medical treatment.

Dating back at least 10,000 years, trepanation is believed to be one of history’s oldest surgical procedures. It’s been practiced all over the world for a variety of reasons, such as treating epilepsy, stopping “possession by evil spirits,” and completing a ritual transformation. Incredibly, a modern version of trepanation is still used in medical settings today. And in recent decades, this procedure has also been utilized by some metaphysical groups.

Dive into the surprisingly long history of this bizarre medical practice.

The Early Years Of Trepanation In Ancient Times

Prismo Archivo/Alamy Stock PhotoA 14th-century illustration of trepanation surgery.

In ancient times, trepanation was an agonizing affair. The medical practitioner would use a tool made of materials like flint, obsidian, or stone to drill or scrape into the patient’s head until they made it through the skull and exposed the dura mater, or the membrane surrounding the brain.

The Greeks and the Romans were among the first groups to create tools specifically for trepanation, including the terebra serrata, which pierced through the skull as the surgeon rolled the instrument between their hands. Interestingly enough, the terebra serrata would later help inspire modern neurosurgery tools like the manual burr hole and the electric drill.

The depth and intensity of the cuts would depend on the medical practitioner’s experience and culture. Most of the operations were performed only one time per person, but some recovered skulls show repeated operations throughout an individual’s lifetime.

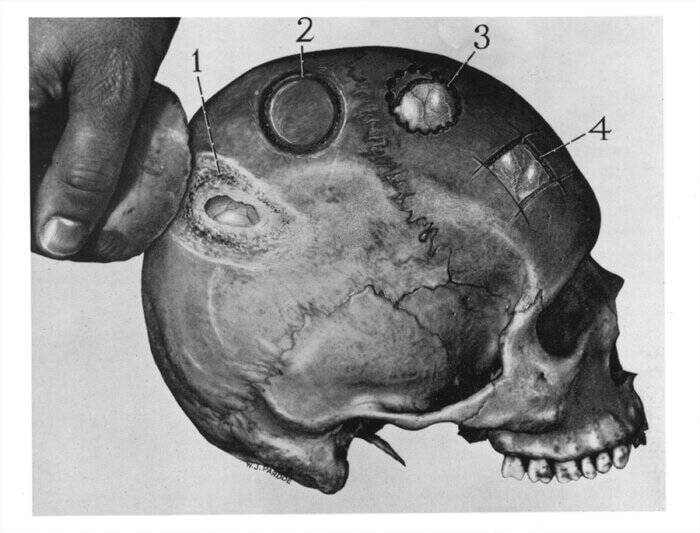

MITAn image showing four different methods of trepanation that have been commonly used throughout history: (1) scraping, (2) grooving, (3) boring and cutting, (4) rectangular intersecting cuts.

For a long time, there were five main methods of trepanation: rectangular intersecting cuts, scraping, cutting a circular groove and then raising off the disc of bone, using a circular trephine or crown saw, and drilling a circle of holes close together and then chiseling the bone between the holes.

The method of scraping layers of bone off the skull was believed to be the most common in prehistoric times, but as the years went on, other methods developed and the tools became more advanced. That said, the scraping method persevered for a long time, lasting until the Italian Renaissance.

But no matter the method, the procedure was always dangerous in ancient times, with patients risking infection, hemorrhage, brain injury, and, of course, death. According to a 2017 study, estimates for survival rates for earlier versions of this procedure hover around 40 percent. However, certain samples of early trepanations have shown a 50 to 90 percent survival rate, depending highly on the skills of the medical practitioners.

The Purpose Behind Trephination, The World’s Oldest Head Surgery

Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 2.0A trepanned skull of a woman from around 3500 B.C.E.

In many cultures, it was thought that drilling or scraping away layers of the skull and exposing the dura mater around the brain to air would benefit the victim and cure them of their physical or mental ailments.

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., Associate Editor-in-Chief in Socioeconomics, Politics, Medicine and World Affairs of Surgical Neurology International, explained:

“Trephination (or trepanation) of the human skull is the oldest documented surgical procedure performed by man. Trephined skulls have been found from the Old World of Europe and Asia to the New World, particularly Peru in South America, from the Neolithic age to the very dawn of history. We can speculate why this skull surgery was performed by shamans or witch doctors, but we cannot deny that a major reason may have been to alter human behavior – in a specialty, which in the mid 20th century came to be called psychosurgery!”

But while most cases of trepanation seem to have treated illnesses or trauma, some ancient skulls from trepanned patients tell another story, such as samples dating back to the Copper Age in modern-day Russia.

According to the BBC, archeologists who were excavating near Rostov-on-Don in Russia in the 1990s discovered unusual trepanation marks on a number of Copper Age skulls. The marks were found on the “obelion” of the patients’ skulls, roughly where a high ponytail would lie. This is a rare spot for a trepanation mark, as it’s extremely dangerous to puncture the obelion.

Because of the danger involved, Maria Mednikova of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow suggested that these trepanations had a ritual purpose. It’s possible that these patients believed trepanation would mystically transform them or give them powers they couldn’t achieve otherwise.

How Did Different Cultures Approach The Practice Of Trepanation?

UC Santa Barbara A trepanned skull from Peru. Circa 1000–1250 C.E.

As previously stated, trepanation has been documented in several different cultures all over the world for millennia. Although many historical accounts of the practice stem from Europe, there is plenty of evidence that cultures in Africa, Oceania, Asia, and the Americas also practiced trepanation.

One of the earliest written accounts of trepanation came from Hippocrates, an ancient Greek physician, in the 5th century B.C.E. In his Hippocratic Corpus, Hippocrates explains how the surgery can be used to treat head wounds, according to the text A Hole in the Head: “Plunge [the trephine] into cold water to avoid heating the bone… often examine the circular track of the saw with the probe… [and] aim at to and fro movements.”

Hippocratic doctors also emphasized the importance of the physicians moving slowly and carefully so that the dura mater would not be injured.

Meanwhile, other areas of the world only recently uncovered evidence of ancient trepanation in their past. In China, for example, it was long thought that the procedure was all but nonexistent in ancient times. But then, in 2007, archaeologists uncovered a number of trepanned skulls in the country — ranging from the Neolithic period through the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Interestingly enough, a historical novel from the Ming Dynasty hints that trepanation may have been more common in China than once believed. In the story, which is set in the Later Han Dynasty, a physician examines a king’s ailing head and says, “Your Highness’s severe headaches are due to a humor that is active. The root cause is in the skull, where trapped air and fluids are building up. Medicine won’t do any good. The method I would advise is this: after general anesthesia I will open your skull with a cleaver and remove the excess matter, only then can the root cause be removed.”

Though some believe this is evidence that trepanation was used on people suffering from severe headaches, many experts doubt trepanning was ever practiced on someone whose only complaint was an aching head. So the novel might’ve simply been a case of the writer taking creative liberties.

While not every culture that practiced trepanation has written accounts about the procedure, researchers have not only uncovered archaeological evidence of the practice in places like the South Pacific, South America, and East Africa, but also how the procedure might’ve been approached.

In the South Pacific, researchers have discovered evidence of trepanation using sharpened seashells, while in Peru, ceremonial knives were believed to have been commonly used. Meanwhile, research over time has shown that East Africa has a particularly rich history of trepanation and the procedure was known at the time of Herodotus. It’s believed that some tribal communities were still practicing it as recently as the early 1990s.

Though the majority of trepanned skulls from world history are believed to have belonged to patients who hoped to treat cranial injuries or neurological diseases, some trepanned skulls likely belonged to people who were participating in a ritual — or trying to cure spiritual ailments.

The Modern Use Of Trepanning In Medical Settings And Metaphysical Groups

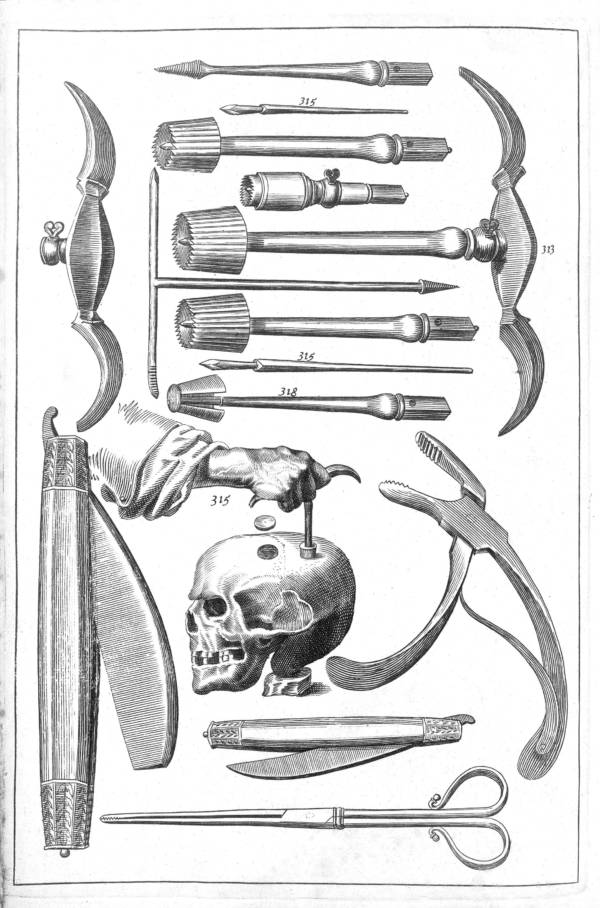

Wellcome CollectionA diagram of trepanning instruments from John Woodall’s The surgeon’s mate, first published in 1617.

Amazingly, there is a modern version of trepanation still in use in medical settings today called the craniotomy. This surgical procedure is often performed to remove a brain tumor or a sample of brain tissue.

Perhaps even more astounding, a small number of people from modern history have voluntarily undergone a trepanation, often to improve their mental health or achieve enlightenment. The idea that trepanation could enhance one’s mental well-being entered the mainstream in Western culture around the 1960s, with The Beatles’ Paul McCartney once claiming that John Lennon asked him and his wife, “You fancy getting the trepanning done?”

Around this time, the idea of self-trepanation emerged as a method to increase one’s mental power and attachment to the metaphysical. Some figures even began to advocate for self-trepanation as a way to improve brain performance and to achieve a permanent “high,” including Dutch librarian Bart Huges, who operated on himself with a dentist drill in 1965.

Science Museum, LondonA trepanation set from London, England. Circa 1771-1800.

Huges would go on to inspire others, including Joey Mellen, the British author of Bore Hole. Mellen went on to perform three trepanations on himself, with the eventual assistance of his partner Amanda Feilding. Feilding was the director of the Beckley Foundation, a group that researches consciousness, and a patient of trepanation — who also operated on herself.

Curious about the procedure and unable to find a doctor willing to perform it on her when she didn’t need it, Feilding used an electrical drill to operate on herself, wrapped her head up in a scarf, ate a steak to replace the iron from the blood she lost, and then went to a party. She claimed that the procedure was “like the tide coming in: there was a feeling of rising, slowly and gently, to levels that felt good, very subtle,” and pointed to an improvement of her dreams, which were “anxious” before the trepanation.

As one might expect, modern experts caution against any form of self-trepanation, as the procedure is incredibly dangerous if you do it incorrectly. In fact, even a medically necessary craniotomy can come with risks, including seizures, strokes, and the possibility of going into a coma.

After reading about trepanation, learn about the gross history of bloodletting. Then, go inside the story of infamous quack doctor Henry Cotton.