The Tuskegee Airmen fought both fascism and racism during World War II — and became some of the most revered heroes of the conflict.

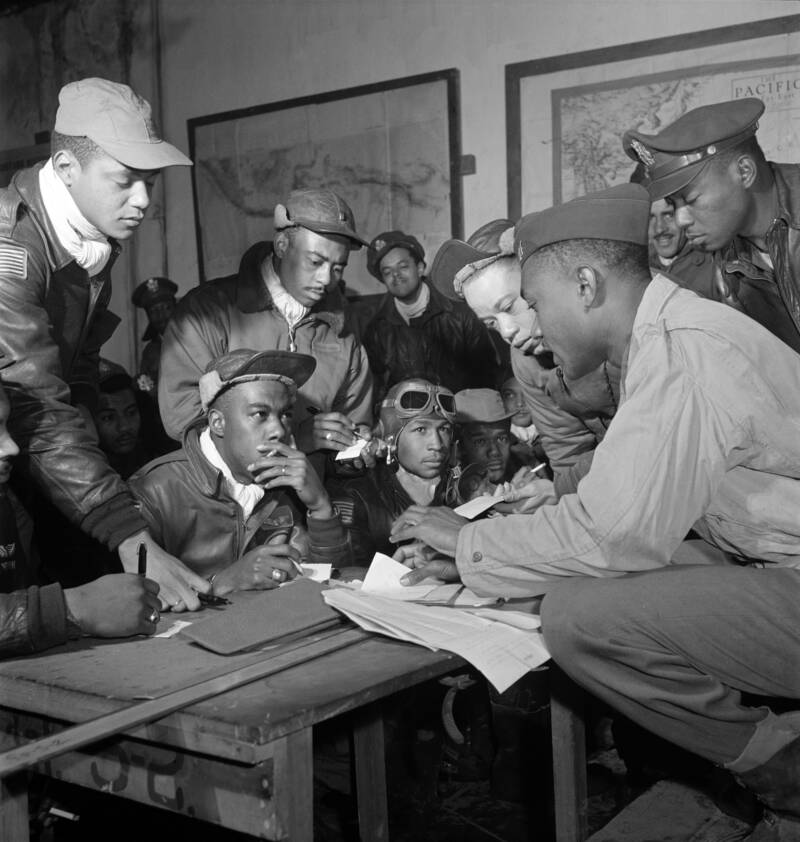

Public DomainA group of Tuskegee Airmen during World War II.

The training of Black pilots in Tuskegee, Alabama in 1941 was called an “experiment” — because the U.S. government expected that it would fail. Instead, it produced the Tuskegee Airmen, thousands of pilots, navigators, mechanics, and bombardiers who bravely fought in World War II.

During the war, the Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 individual sorties. Though they were often given older, slower planes — and were required to fly more missions than white airmen — they excelled in combat.

Their fearless fighting prowess proved that Black people were more than capable of being military pilots, and eventually helped lead to the desegregation of the United States Armed Forces in 1948.

Inside Black Americans’ Fight To Fly

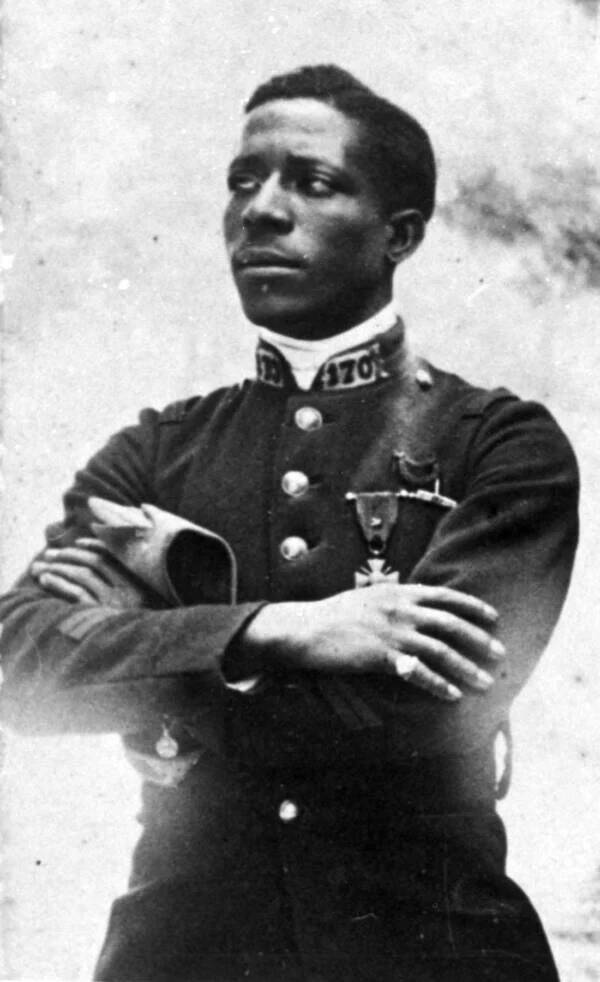

Before World War II, it was next to impossible for Black Americans to become military pilots. Even skilled aviators like Eugene Bullard were turned away from the U.S. military (Bullard fought for France instead during World War I, to great acclaim), and official government policy suggested in deeply racist terms that Black people were ill-equipped to be soldiers at all.

Public DomainBefore the Tuskegee Airmen, talented Black pilots like Eugene Bullard were turned away from the U.S. military.

“An opinion held in common by practically all officers is that the Negro is a rank coward in the dark,” a 1925 study from the U.S. Army War College stated. “His fear of the unknown and unseen will prevent him from ever operating as an individual scout with success. His lack of veracity causes unsatisfactory reports to be rendered, particularly on patrol duty.”

Civil rights organizations like the NAACP and Black newspapers like The Chicago Defender and The Pittsburgh Courier fought back against this racist view. And in September 1940 — with war raging in Europe — the U.S. government agreed to let the U.S. Army Air Corps (AAC) train Black pilots.

On January 16, 1941, Secretary of the Army Henry L. Stimson gave the go-ahead for a “Negro pursuit squadron” of pilots who would be trained in Tuskegee, Alabama. According to the National WWII Museum, Tuskegee was selected because of its location, which had good weather for flying, and because the Tuskegee Institute was already training Black civilian pilots.

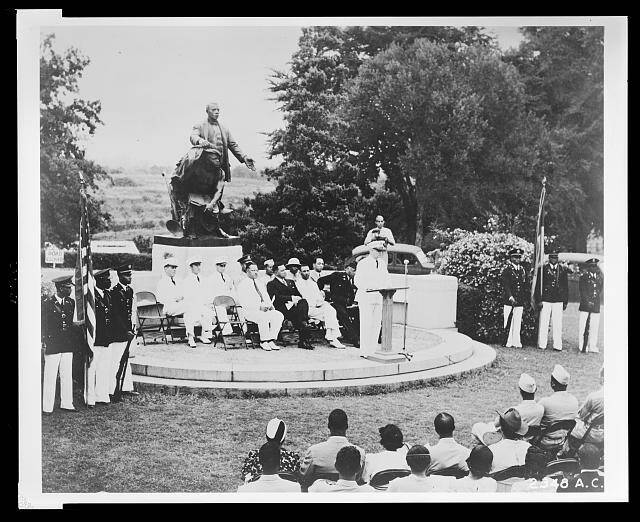

Library of CongressMaj. Gen. W. R. Weaver speaking at the Tuskegee Institute in 1941, marking the beginning of training Black military pilots.

That March, President Franklin D. Roosevelt officially activated the all-Black 99th Pursuit Squadron (which would later be known as the 99th Fighter Squadron). And thus, the story of the Tuskegee Airmen began.

The Historic Formation Of The Tuskegee Airmen

“The Air Force didn’t want us — the Army Air Corps, the brass and what not,” Tuskegee Airman Leroy Roberts Jr. later recalled. “And we were not given the same opportunity as white cadets that were there for training… there had been some stupid study earlier on in which said that we didn’t have what it took to be able to master the — the business of flying airplane.”

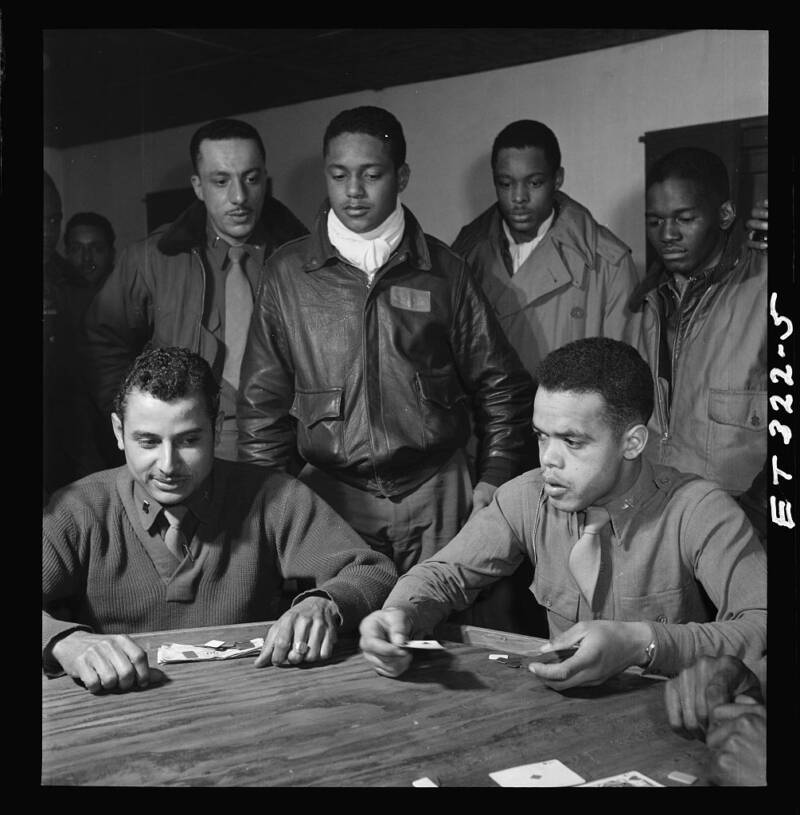

Library of CongressLeroy Roberts Jr. — standing, third from left — with other Tuskegee Airmen in Italy. Circa 1945.

He added: “But with all the pressure, building as it did, they decided finally to build this Army airfield down there in Tuskegee, Alabama… The thought at that time was that we would not succeed. We were expected to fail. And of course we was determined that we would not fail, and consequently we — we succeeded in doing what we had to do and in good fashion.”

The so-called experimental training drew Black Americans from all over the country. Almost 1,000 of them would become pilots, but about 14,000 would train as navigators, engineers, mechanics, and bombardiers. And though most of the Tuskegee Airmen were men, they included some women, too.

The program got an early publicity boost in March 1941, when First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Tuskegee Institute. She was taken on a flight by the chief flight instructor in the program, Charles Alfred “Chief” Anderson, and later recounted her experience in her newspaper column “My Day.”

“Finally we went out to the aviation field,” the first lady recounted in her April 1st column, “where a Civil Aeronautics unit for the teaching of colored pilots is in full swing. They have advanced training here, and some of the students went up and did acrobatic flying for us. These boys are good pilots. I had the fun of going up in one of the tiny training planes with the head instructor, and seeing this interesting countryside from the air.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and MuseumEleanor Roosevelt with Charles Alfred “Chief” Anderson, the Tuskegee Institute’s chief flight instructor.

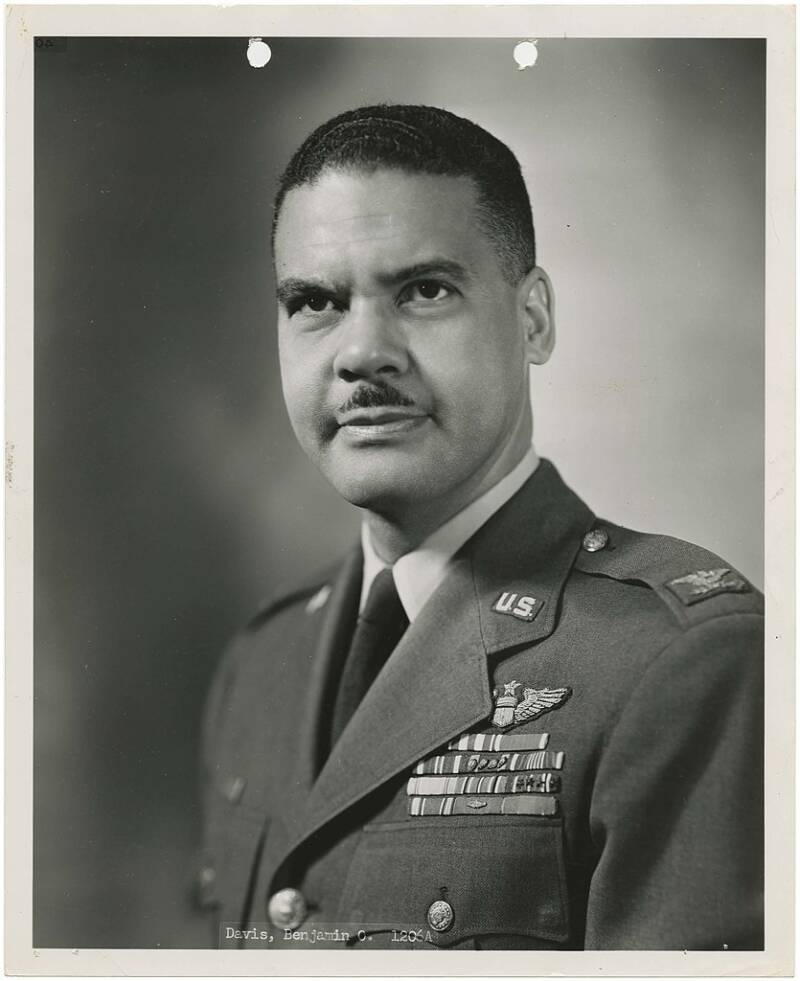

On March 7, 1942, the first class of cadets graduated from the Tuskegee Army Air Field. These men — Second Lieutenants Lemuel R. Curtis, Charles DeBow, Mac Ross, George Spencer Roberts, and Captain Benjamin O. Davis Jr. — were the first Black American military pilots in American history.

And these men would soon prove themselves on the battlefield.

The Tuskegee Airmen’s Incredible Heroism During World War II

In April 1943, the 99th Pursuit Squadron was sent to fight in North Africa and then Sicily. But the Tuskegee Airmen were initially given older, clunkier planes than their white counterparts, a big obstacle while flying.

“The Tuskegee Airmen initially flew the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. This was a prewar design and almost obsolete,” the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum reports. “They were briefly equipped with Bell P-39 Airacobras in March of 1944. It’s widely thought that this was an even less capable design and it was used by very few of the U.S. front line fighter units in the war.”

U.S. Air ForceFirst Lieutenant Charles B. Hall, in his Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. The swastika represents a Luftwaffe plane he shot down.

And it wasn’t just Tuskegee Airmen pilots who faced racist obstacles. Mechanics did too. Airman Walter Suggs told NPR that the U.S. government “expected [the airmen] to fail and they kind of put them in that situation, the Afro-Americans, so they would fail. So they wouldn’t give them parts or anything like that.” Still, the men found creative solutions to their problems.

For example, Suggs explained, if an airplane returned with a “hole” in it and the airmen couldn’t get the parts that they needed, “they would go out and measure it and then they would go into the mess hall… where you could find these empty cans. They would take them, cut them up into a patch, and they would take it and go out and rivet it to the aircraft.”

Despite these ongoing challenges, the Tuskegee Airmen served valiantly on the battlefield. Known for the distinctive red tails on their planes, they flew more than 15,000 individual sorties, destroyed 36 German planes in the air and 237 on the ground, and demolished approximately 1,000 enemy rail cars and transport vehicles. And when they served in bomber crews with the 477th Bombardment Group (the predecessor of the 477th Composite Group) in 1944, the Tuskegee Airmen were so effective in combat that a rumor emerged that they hadn’t lost a single bomber.

(This wasn’t quite true — some two dozen of the bombers they escorted were shot down — but they did have a much higher success rate than other American fighter escort groups during World War II.)

Library of CongressTuskegee Airmen in Italy. March 1945.

Some Tuskegee Airmen also distinguished themselves as fighter pilots. Colonel Lee Archer shot down four enemy aircrafts, including three in one day. Colonel Roscoe Brown shot down a German Me-262 jet, despite its superiority to his own P-51. And Brigadier General Charles McGee flew over 100 missions in World War II, a feat he’d later repeat in Korea and Vietnam.

Despite their courageous service, however, the Tuskegee Airmen faced a rough landing when they returned to the United States.

A Disappointing Return Home — And The Later Desegregation Of The U.S. Armed Forces

Upon returning home to the United States after the end of World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen were disheartened to find that little had changed.

“We had the hope that — after we had accomplished what we did — that we’d be accepted in better fashion than we had been prior, but things were essentially the same; they had not changed that much,” Leroy Roberts Jr. recalled. “We were hopeful that they would — and people would have paid more attention to what we did, what we accomplished, what we sacrificed, if you want to call it that. But didn’t make that much of a difference.”

San Diego Air and Space Museum’s Library and ArchivesA group of Tuskegee Airmen at Luke Field in Arizona. Circa January/February 1946.

From the moment that many of them arrived home, this lack of progress was clear. According to the National WWII Museum, few Tuskegee Airmen were celebrated when they arrived home by ship. In fact, many of them were told to disembark at a different exit than their white counterparts.

But their courageous service did mark an important step forward. Just a few years after World War II ended, on July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the desegregation of the U.S. Armed Forces.

And many Tuskegee Airmen went on to have successful military careers. Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr. later became the first Black general in the United States Air Force; General Daniel “Chappie” James became the first Black four-star general in the Air Force (or in any branch of the military).

Public DomainBenjamin O. Davis Jr. is one of the most successful Tuskegee Airmen.

Overall, the Tuskegee Airmen also earned more than 850 medals for their valor, including 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses. And decades after their service, some 300 surviving Tuskegee Airmen were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal from President George W. Bush in 2007.

As such, the so-called “experiment” was more than a success — it profoundly changed the course of American history. The Tuskegee Airmen proved that they were capable of flying and fighting. And even though they returned home to find segregation still firmly in place in the Jim Crow South, their service was an important step toward a more equal society.

“It makes — it appears to me it makes more of a difference now,” Roberts remarked. “People are paying more attention to what we did, what we accomplished then back then, when I think it should have counted most. Because there are an awful lot of guys that are no longer with us today that have not had the enjoyment of this sort of appreciation.”

After reading about the Tuskegee Airmen, discover the story of the all-Black Harlem Hellfighters and their impressive service during World War I. Or learn about the Buffalo Soldiers, the Black rangers who patrolled the Wild West.