Tycho Brahe kept a drunken elk in his entourage, supposedly had an affair with the queen of Denmark, and totally changed our understanding of the universe itself.

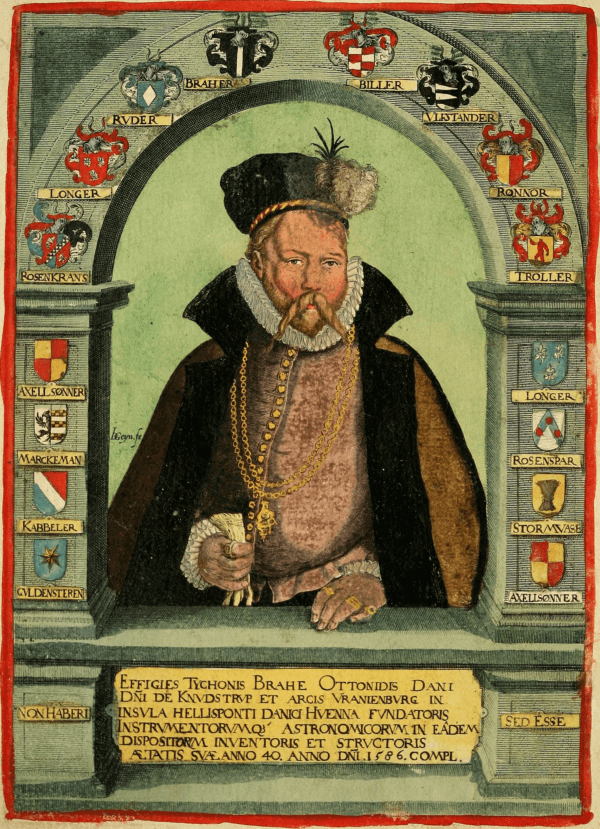

Wikimedia CommonsTycho Brahe dazzled Europe with his scientific acumen and has since fascinated historians thanks to his unusual private life.

Some 400 years after his death, Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe remains relatively unknown to most people today. Nevertheless, his planetary observations and other celestial discoveries paved the way for future scientific breakthroughs that helped shape our very understanding of the world as we know it — and his private life was just as fascinating.

The Unusual Early Life Of Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe and his twin brother were born to one of Denmark’s noble families in December of 1546. Brahe’s twin, sadly, died before he had even been baptized, leaving him as the eldest of his parents’ 12 children and the sole heir to his family’s ancestral castle and fortune.

Yet for the majority of his childhood, Brahe was actually raised by his wealthy uncle, Jørgen Thygesen Brahe. The reasons behind young Brahe’s living situation have never been fully explained and some historians claim that the boy was actually kidnapped by his wealthy, but heirless, uncle.

Whatever the reason, Brahe’s father eventually came to some kind of agreement with his uncle and the boy fondly recalled that his uncle, “generously provided for me during his life until my eighteenth year; he always treated me as his own son and made me his heir.”

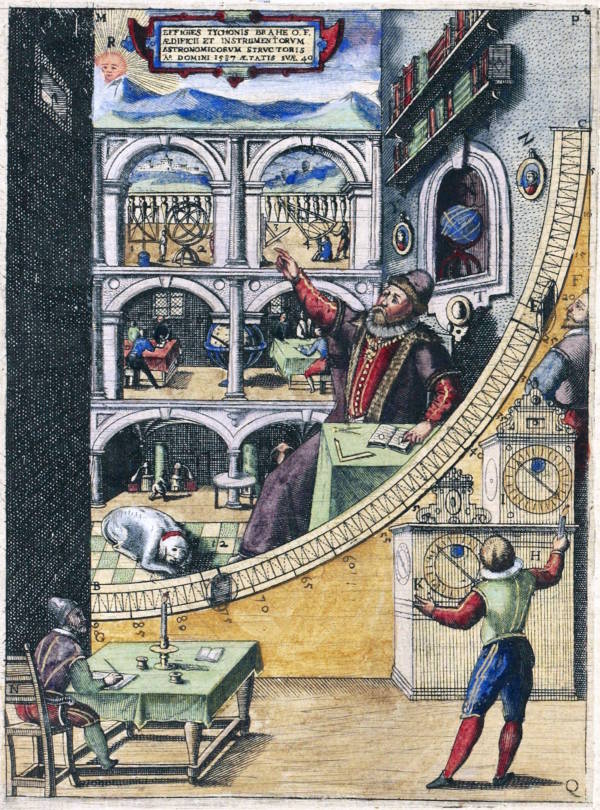

Wikimedia CommonsA mural from the observatory Tycho Brahe built with funding from the King of Denmark.

Brahe’s Foray Into Astronomy

When Tycho Brahe was just 13, he was sent by his uncle to study law at the University of Copenhagen. In 1560, however, Brahe witnessed an event that would change not just his course of study but the course of his entire life.

European astronomers had predicted that there would be a total solar eclipse on August 21 of that year. At the time, the science of astronomy was still somewhere between the realms of science and superstition. When the Sun did in fact disappear behind the moon on the appointed day and plunged the world into darkness, people were astounded.

Wikimedia CommonsTycho Brahe

For some people, the announcement of the eclipse was a signal to panic and in France, people flocked by the dozens to make their confessions to priests. For Tycho Brahe, however, the momentous event marked a changing point in his life that he could never forget.

Although he still obeyed his uncle’s wishes and studied the law by day, by night he began to study the heavens.

Brahe purchased several astronomical instruments and began to read the few books about astronomy that were available. The science had changed little since the days of the Greeks. And Ptomley’s Almagest, written around 150 A.D., still served as the base reference for most of the world’s astronomers.

Almagest not only explained the motions of the Sun, Moon, and known planets (which allowed astronomers to make fairly accurate predictions about eclipses) but also provided the ecliptic coordinates of more than 1,000 stars. Soon, however, Tycho Brahe would be making discoveries that proved this millennia-old gospel of astronomy a bit out of date.

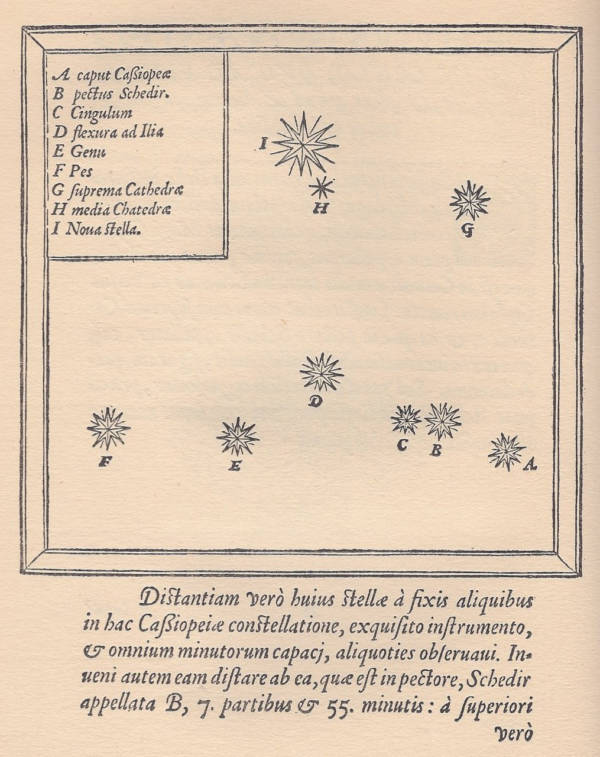

Wikimedia CommonsThe “stella nova” (new star) that Tycho Brahe discovered in the constellation Cassiopeia.

A Missing Nose And A Celestial Discovery

Tycho Brahe then spent the decade between 1560 and 1570 studying at universities in Copenhagen in Denmark, and Leipzig, Wittenberg, Rostock, Basel, and Augsburg in Germany. During the course of his studies and travels, he accumulated a vast wealth of knowledge about mathematics and astronomy, acquiring an impressive collection of scientific instruments along the way.

In 1566, an argument over either a mathematical calculation or an astronomical prediction (depending on the source) escalated into a violent sword duel, during which the scholar lost a portion of his nose. For the rest of his life, he wore a type of metallic prosthetic over his missing nose, reportedly made of gold or silver (but which a modern exhumation actually revealed to be brass).

Brahe returned to Denmark around 1570 and built himself an observatory at the former monastery of Herrevad Abbey, which had recently come into possession of one of his relatives. It was at Herrevad in 1572 that Tycho Brahe made a strange observation one November night.

Brahe’s eyes were drawn to a star in the night sky that was shining brighter than the planet Venus. Even more surprising, the star was appearing in a spot no star had ever been recorded, in the constellation Cassiopeia.

Internet Archive/FlickrTycho Brahe

Since antiquity, astronomers had subscribed to the doctrine of celestial immutability laid out by the philosopher Aristotle. The doctrine essentially stated that the universe, which was ruled by the heavens, was perfect and unchanging. If the stars were constant, it did not make sense that Brahe could be seeing an entirely new one in a constellation that had been mapped out for centuries.

Upon further study, he realized that not only had he discovered a “new star,” but that it was a fixed star that was further away than the Moon and all the other planets.

In 1573, he recorded his findings in the book De Nova Stella, which garnered him renown as an astronomer throughout Europe. In the book, the title of which translates to “On the New Star,” Tycho Brahe also established the term “nova” to describe a new star (although the particular star he discovered has since been classified as a supernova).

Wikimedia CommonsTycho Brahe named his laboratory “Uraninborg” after the Greek muse of astronomy.

Tycho Brahe Finds A New Way Of Looking At The Heavens

This astronomical discovery was an important one, as the new star Tycho Brahe discovered upended everything that had previously been assumed about the heavens.

If everything in the universe was not fixed and permanent, then almost anything could be possible. Whereas previous astronomers had focused merely on observing the motions and patterns they thought were already determined, Brahe used meticulous calculations and calibrations of his instruments to note several important anomalies that had never before been noticed and which, in turn, led to the shattering of several other commonly held theories and the establishing of several new theories.

Brahe began lecturing on astronomy at his alma mater, the University of Copenhagen, and had garnered an impressive following across Europe. One of the people most interested in Brahe’s work was none other than King Frederick II of Denmark himself.

The king was impressed enough to finance the building of an observatory for the astronomer on the island of Hven near Copenhagen, which would soon become one of the most prestigious on the continent.

Meanwhile, Brahe’s personal life continued to be nearly as remarkable as his professional one.

In 1573, he scandalized his noble family by marrying the daughter of a peasant, Kirstine, with whom he had eight children. The astronomer not only brought in Italian artists to decorate his observatory (which more closely resembled a castle) but kept a court of eccentric figures around him. This bizarre entourage included a jester, a dwarf named Jepp who also supposedly had psychic powers, and a prized pet elk that the astronomer used to ply with beer until it met its end after a drunken fall down the steps.

Wikimedia CommonsStatue of Tycho Brahe and his assistant (and possible murderer) Johannes Kepler.

A Swift Downfall And Rumors Of A Bizarre Death

Tycho Brahe soon fell out of royal favor after the death of King Frederick II and the king’s heir, King Christian IV had a severe dislike of his father’s astronomer.

But why the sudden fall from grace? It was speculated that the king’s animosity stemmed from the rumor that Brahe had been having an affair with his mother, Queen Sophie, a rumor that also may have inspired Shakespeare’s most famous tragedy, Hamlet.

Brahe was forced to flee Denmark in 1597 and eventually settled in Prague, where he enjoyed the patronage of Emperor Rudolf II.

The astronomer was attending a banquet in his adopted city in 1601 when he suddenly fell ill and died 11 days later at the age of 54. Then the colorful stories swirling about the famed astronomer and his sudden death started to spread.

Wikimedia CommonsTycho Brahe’s assistant Johannes Kepler became a famous astronomer in his own right, although he may have risen to prominence through diabolical means.

Although Tycho Brahe officially died due to a kidney condition, there have long been theories that he was actually poisoned. These theories were only strengthened when researchers analyzing his remains in the 1990s found high levels of mercury in his hair.

One suspect in the case was King Christian IV, who already had a recorded hatred for Brahe and had previously run him out of the country. Yet other researchers have determined that the potential murderer was Brahe’s own assistant and fellow astronomer, Johannes Kepler.

Brahe was famously possessive of all the knowledge he had recorded, not even allowing his protege to access it. This led to frequent clashes between the two. Kepler admitted that he often succumbed to the “rage-provoking force” of the planet Mars and would certainly have had access to mercury while working in Brahe’s lab, as well as easy access to Brahe himself to administer the doses.

But perhaps the most damning evidence is that after Brahe’s death, Kepler openly admitted to stealing his research, later explaining, “I quickly took advantage of the absence, or lack of circumspection, of the heirs, by taking the observations under my care, or perhaps usurping them.”

Kepler would develop his own theories regarding astrology and planetary motion that would, in turn, lay the groundwork for the modern forbears of the science, including Isaac Newton. These theories, of course, would never have been possible without the research Kepler had taken from his own teacher, the widely unknown yet altogether fascinating Tycho Brahe.

After this look at Tycho Brahe, read up on Wernher von Braun, the Nazi scientist that sent the U.S. to the moon. Then, learn the most fascinating facts about Isaac Newton.