Without Vincenzo Peruggia's daring Mona Lisa theft operation in 1911, would the iconic painting even be well-known today?

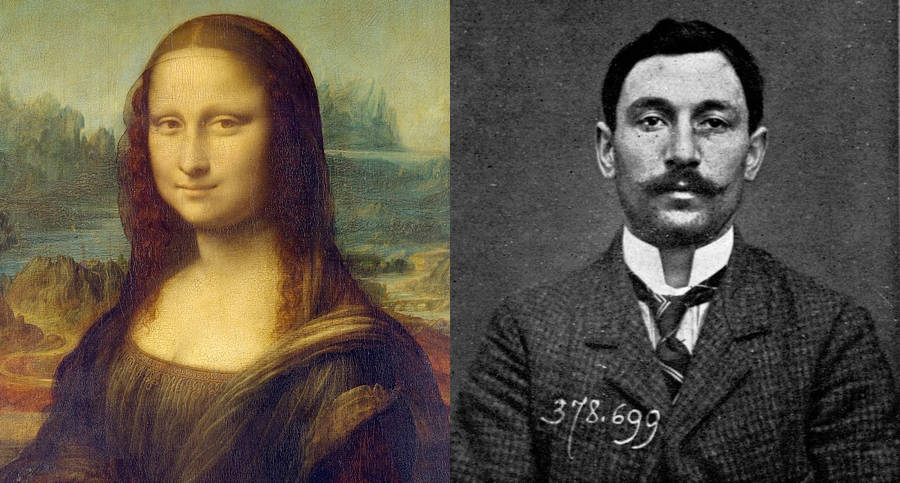

Wikimedia CommonsLeft: The Mona Lisa. Right: Vincenzo Peruggia, the man responsible for stealing it from the Louvre in 1911.

The Mona Lisa just might be the most recognizable face on Earth. Featured in countless TV shows and movies, parodied in different forms across the globe, and written about in art books of every language, the Mona Lisa has a face that draws more than 7 million people to the Louvre in Paris each year.

Each one of those visitors will see that up close, the Mona Lisa is actually very small, just 30″ x 21″. It isn’t massive or striking or undeniably moving in the way that many of the other Renaissance works are. In fact, when the Mona Lisa was first placed in the Louvre in 1797, it was on a wall with a number of other paintings, not standing alone in the spotlight as it is now.

The Mona Lisa is, of course, a great work of art by a revered artist, Leonardo de Vinci, but his skills are not actually what made the painting famous.

Mona Lisa’s true fame came from a petty Italian art thief named Vincenzo Peruggia. On the morning of Monday, August 21, 1911, Peruggia walked unnoticed out of the Louvre with the Mona Lisa hidden under his smock.

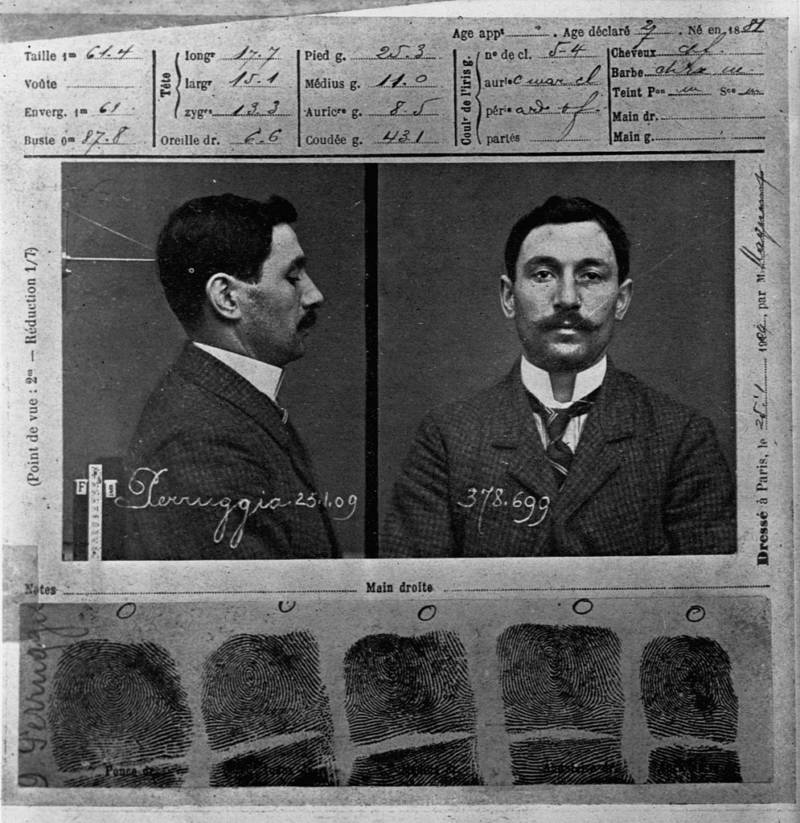

Wikimedia CommonsVincenzo Peruggia’s police record. 1909.

Peruggia wasn’t an unusual face in the museum. He was a handyman, occasionally hired to work on protective glass for the displays. He worked with a number of expensive and beautiful paintings at the Louvre and other museums. So, why swipe the Mona Lisa?

For Vincenzo Peruggia, it was a matter of patriotism. He mistakenly thought that the Mona Lisa had been stolen from Italy during the Napoleonic era and he believed that it was his job to return it to its home country.

Most accounts of the theft claim that he hid in a closet in the museum on Sunday night, knowing that it would be closed on Monday and that he could safely swipe the painting and leave. However, in Peruggia’s own account during his interrogation two years later, he said that he simply came in on Monday morning along with other workers, waited until the gallery that housed the Mona Lisa was empty, took the painting off the wall, wrapped it in his smock, and walked out, just like that.

In fact, the staff at the Louvre did not even notice that the painting was missing until the next day. Paintings were sometimes taken off the wall to be photographed, so it wasn’t unusual that one was missing from the wall. However, when security checked with the photographers, they discovered that the painting had been stolen.

While police launched an investigation, Peruggia was home slipping the Mona Lisa into a trunk in his apartment with no idea that his sticky fingers had just changed the course of art history.

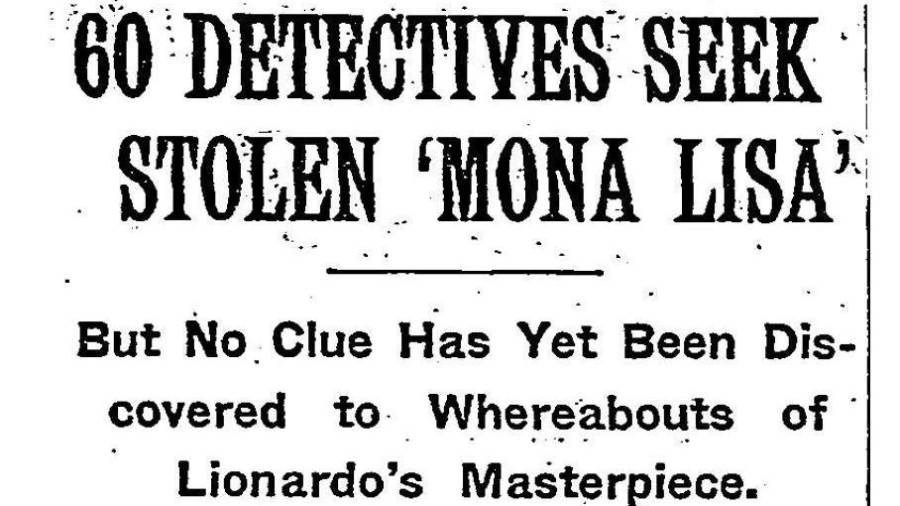

The New York TimesThe New York Times headline from August 24, 1911.

Throughout the next two years, the heist of the Mona Lisa became international news. The story spread via newspapers all across France, and all around the world, even appearing in The New York Times.

Meanwhile, the police searched desperately for the thief and investigated many suspects, including renowned poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had once called for the Louvre to be burned down and who was now in possession of several small statues stolen from the Louvre. Police thought that the man who had stolen the statues might also have the Mona Lisa.

When police questioned Apollinaire about the Mona Lisa and the statues, he implicated his friend, a young Spanish painter by the name of Pablo Picasso, in the latter crime. Both Apollinaire and Picasso reportedly cried under interrogation, and the police ultimately realized that neither was the man that they were looking for.

Back at the Louvre, the museum had been closed for a week in the wake of the theft. But then, when it reopened, there were lines out the door just so that guests could come in and see the place where the Mona Lisa once was. People way out in California knew exactly what this little painting from France looked like because they’d been seeing it in newspapers as part of this sensational crime, over and over again.

Had Vincenzo Peruggia stolen any other painting, that stolen work of art could perhaps have just as easily become the most famous painting in the world and the Mona Lisa would not be the household name that it is today.

But because of the theft, the Mona Lisa became the first work of art to be seen and shared globally, in a time when mass communication was just in its infancy. A work of art that had once been just a small rectangle on a wall filled with paintings was now at the center of a global scandal.

Meanwhile, Peruggia’s plans to sell the painting back to an Italian art gallery were interrupted. With the Mona Lisa’s newfound fame, any attempt to turn it in for a reward or offer to sell it could result in his arrest. So, there it sat, in a trunk, waiting for two years.

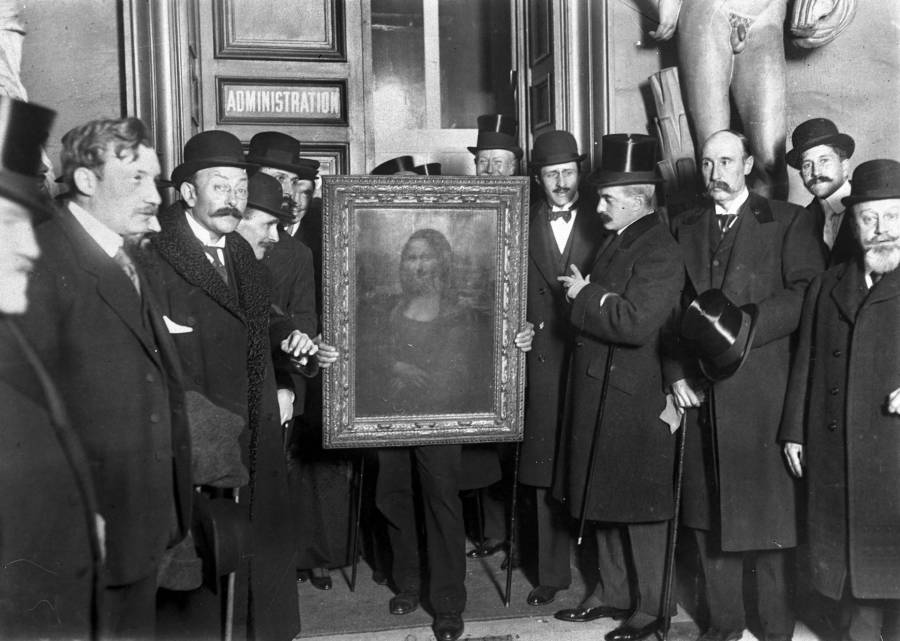

Wikimedia CommonsUffizi Gallery director Giovanni Poggi (right) inspects the Mona Lisa during its brief stay there. Florence. December 1913.

Finally, in 1913, Vincenzo Peruggia’s patience had finally dwindled. He contacted Alfredo Geri, an art dealer in Florence, and offered to return the Mona Lisa to its “homeland” in exchange for a reward. Geri told Peruggia to meet him at the Uffizi Gallery to authenticate the painting.

When Peruggia dropped it off, Geri promised to hold it for safekeeping, but instead contacted the police as soon as Peruggia left. The art thief was arrested in his hotel, the Mona Lisa was recovered, and the crime that had rocked the world was now at an end.

Roger-Viollet/Getty ImagesPeople gather around the Mona Lisa in Paris on January 4, 1914, the day of its return.

The Uffizi Gallery displayed the painting for two weeks before it was officially returned to the Louvre on January 4, 1914. Since then, there have been a few incidents of people trying to damage the Mona Lisa, but no more thefts. Today, the painting has its own wall at the Louvre, protected by climate-controlled, bulletproof glass.

As for Vincenzo Peruggia, he served six months in prison and Italy praised him for his patriotism. He served in the Italian army during World War I and eventually moved back to France where he owned a paint shop until his death in 1925.

After this find out all the facts about the Mona Lisa. Then, have a look at the nude Monna Vanna sketch that may have been Leonardo da Vinci’s precursor to the Mona Lisa.