Weegee, the world's first paparazzo, documented the brutality of New York's gang wars of the 1930s and 1940s like no one before or since.

While the Rockefellers and Carnegies gallivanted around luxurious Manhattan hotspots in the early 20th century, Arthur Fellig had his eyes, and camera, on a very different New York City.

In the 1930s and ’40s, life in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where Fellig took many of his photos, was marked by violence, crime, and death. Fellig, who went by Weegee, documented it all. Following emergency vehicles to crime scenes and gang war shootouts, Weegee later recounted that he “had so many unsold murder pictures lying around my room…I felt as if I were renting out a wing of the City Morgue.”

Over the years, his depictions of New York’s seedy, blood-soaked reality prompted many to consider him the world’s first paparazzo — and for masters of cinematic fiction such as Stanley Kubrick to later collaborate with him.

As the following exclusive photos from National Geographic show, it’s easy to see why:

The Life Of Weegee

National GeographicWeegee holding his camera.

Weegee's story is similar to so many of those who lived in New York City at the time. Born on June 12, 1899, in present-day Ukraine, in 1909 the son of a rabbi emigrated to the United States with his family. In 1935, after working several odd film-related jobs, Weegee began his life as a freelance photographer, and without any formal training.

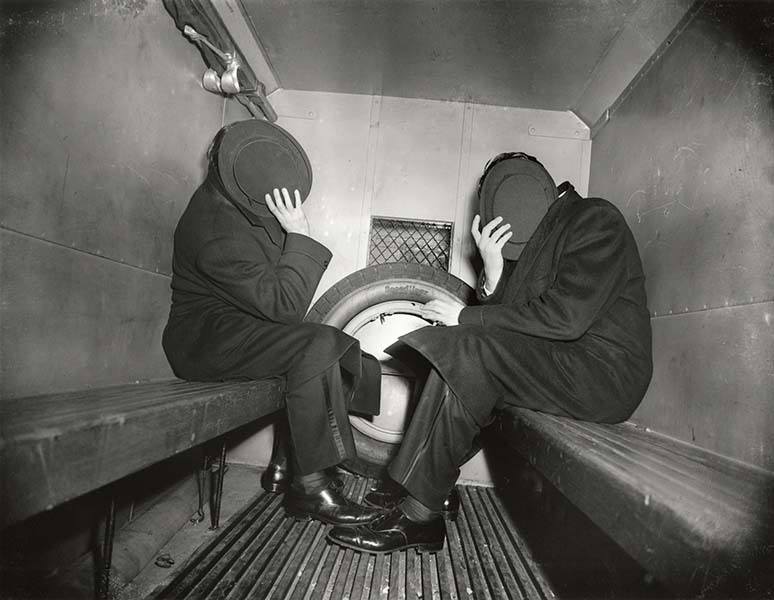

In ways that call to mind 2014's Nightcrawler, Weegee — who got his nickname from 'Ouija' for his tendency to beat cops to a crime scene — patrolled the onyx streets of New York City in his car each night, waiting for the blood to spatter. Equipped with a police radio, typewriter, developing equipment (and, crucially, cigars and extra underwear), Weegee would drive to the scene of the crime, shoot and develop the photos in his trunk, and deliver them to the dailies.

Soon enough, Wedge's macabre photos — whose grit was enhanced by his then-uncommon use of flash — found their way inside the pages of everything from the Daily News to the New York Post to the Herald Tribune.

That's not to say that Weegee's work was simply inspired by violence for its own sake. The photographer, whom the New York Times describes as a "congenital, unradical leftist," made an effort to "[pick] a story that meant something."

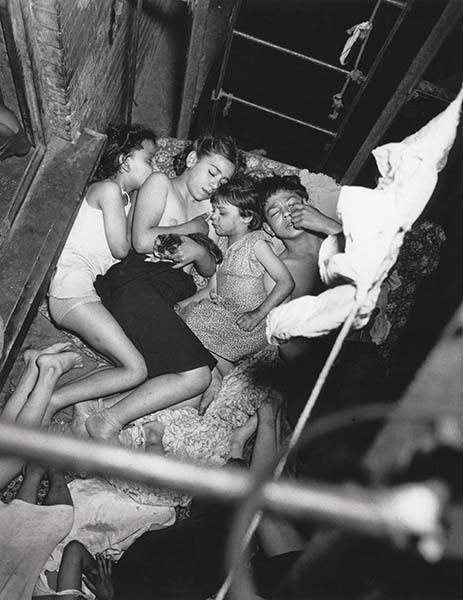

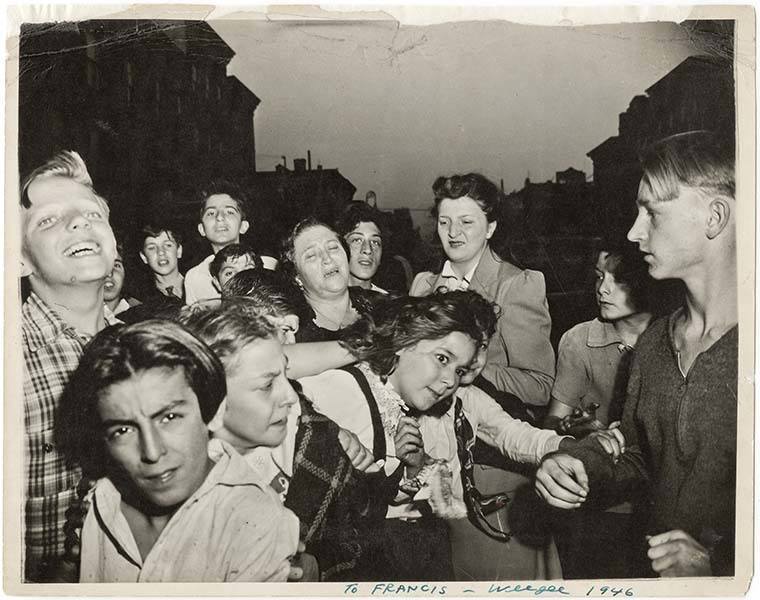

Steeped in a populist aesthetic, Weegee would say that he attempted to "humanize the news story." In practice, this meant that he would photograph everything from segregation and the violence of city race relations to the everyday life of the poor. It also meant photographing people's responses to crime and chaos, not just the crime itself.

Weegee perhaps best described this strategy when describing a tenement housing fire. "I saw this woman and the daughter looking up hopelessly," Weegee said. "I took that picture. To me, that symbolized the lousy tenements, and everything else that went with them."

His work, while sensational and sometimes staged, would leave a lasting mark in photojournalism and the city. Indeed, his crime photos and their widespread dissemination placed pressure on city law enforcement to better respond to organized crime and reduce the prevalence of its "bloody spectacle." Likewise, many credit his work for the rise of tabloids.

In 1968, Weegee returned to New York City, where he would die at age 69. In a world bombarded by aspirational images of glitz and glamour, Weegee's work and philosophy of photography still offers a valuable lesson. "Many photographers live in a dream world of beautiful backgrounds," Weegee once said. "It wouldn't hurt them to get a taste of reality to wake them up."