The Time Raw Meat Fell From The Sky Above Kentucky

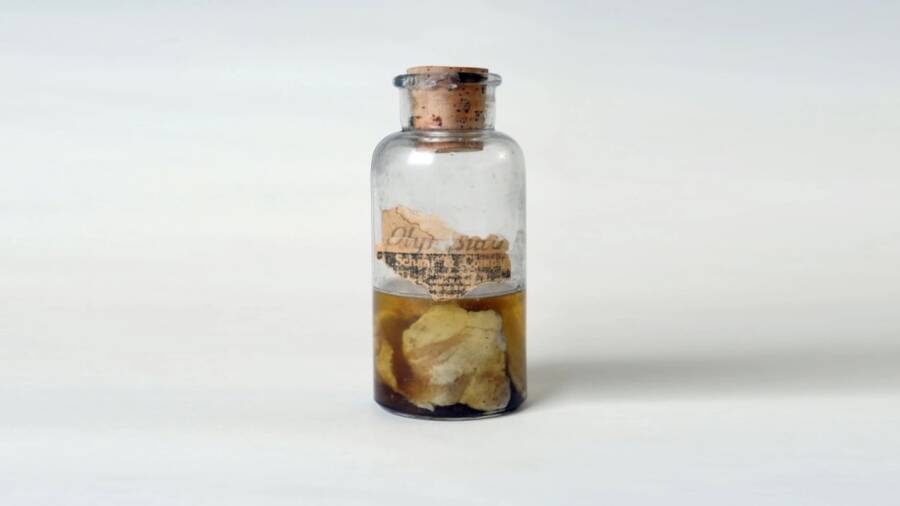

Kurt Gohde/Transylvania UniversityMeat stored at Transylvania University from the 1876 meat shower.

It was a clear March morning in 1876 in Bath County, Kentucky. Mrs. Crouch, the wife of a local farmer, was out in her yard when suddenly, without warning, raw meat began falling from the sky.

The chunks varied in size, with some measuring up to four by four inches. The meat rained down for several minutes before the sky cleared again. Known as the Kentucky Meat Shower, this strange incident is one of America’s weirdest historical events, and it continues to baffle people to this day.

The shower remained mostly contained to an area about the size of a football field, leaving chunks of meat on fences, the roof of the farmhouse, and the ground. To the Crouches, this sudden downpour of flesh was either a miracle or an ominous warning — but whichever it was, it certainly drew attention. Soon enough, their neighbors were flocking to the property to witness the bizarre scene.

Naturally, there were many questions, but one rose to the forefront of everyone’s mind: What type of meat was it?

The answer proved to be remarkably difficult to suss out. Local consensus suggested it was beef based on color and smell, though a hunter claimed the “uncommonly greasy feel” more closely resembled bear meat. A few braver men tasted pieces, concluding that it was either venison or mutton. A local butcher, on the other hand, disagreed entirely, stating it “tasted neither like flesh, fish, or owl.”

Authorities sent samples to chemists and universities nationwide, but experts couldn’t reach an agreement on the meat’s identity. And of course, the weird historical event spawned numerous theories ranging from scientific to absurd.

One writer, for instance, proposed a “meat-eor” shower theory that involved a belt of meat revolving around the Sun, while another scientist suggested that it was Nostoc, a jelly-like cyanobacteria that blooms after rain.

Lairich Rig/Wikimedia CommonsNostoc overtaking a bridge.

The most widely accepted explanation was, unfortunately, a rather unpleasant one. Multiple sources, including the Crouches and chemists, theorized that a flock of vultures had overfed and then simultaneously vomited as a result, with one bird’s regurgitation triggering a chain reaction of nausea among the others. One chemist even noted that “when in a flock one commences the relief operation, the others are excited to nausea, and a general shower of half-digested meat takes place.”

The townspeople accepted the vulture theory as the most plausible explanation, apparently unfazed that several among them had already consumed pieces of what was likely regurgitated carrion.