After the Revolutionary War, most Americans were ready for peace. But in 1791, a tax on distilled spirits sparked rebellion once again as thousands took up arms against their newly-founded country in the Whiskey Rebellion.

Unknown/Metropolitan Museum of Art

President George Washington leading a militia to stop the Whiskey Rebellion.

In 1794, farmers in western Pennsylvania rose up against the newly-founded United States. When the U.S. government sent tax collectors west, farmers grabbed their muskets to defend their rights. At one point, an armed mob of 7,000 people marched in Pittsburgh.

Washington called these farmers “insurgents” and led a militia to quell the rebellion. It’s been called the greatest crisis of Washington’s presidency. But what was the Whiskey Rebellion in the first place?

What Was The Whiskey Rebellion?

In the wake of the American Revolution, many states struggled under massive amounts of debt. In 1790, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton proposed a plan where the federal government would take over state debt.

But the move left the federal government strapped for cash, and in 1791 Congress passed a whiskey tax to raise money.

John Turnbull/Peabody Essex MuseumAlexander Hamilton pushed for the whiskey tax.

This tax hit frontier farmers hard. Small producers paid a higher rate than large producers, and the federal government demanded cash payments at a time when many farmers didn’t use cash at all.

Even more critically, many farmers on the American frontier converted their grain into whiskey, since transporting grain to the east was difficult. The new tax took a big cut into the main source of income for many families.

In western Pennsylvania, farmers resisted the tax, proclaiming that it violated their rights and interfered with their business.

For the next three years, violent clashes between farmers and government officials on the frontier defined the Whiskey Rebellion.

The Whiskey Tax Hurt Frontier Farmers

The whiskey tax didn’t just hit western farmers economically. It also imposed new regulations on alcohol production. Under the law, every distillery in the country had to be registered. Further, violators who didn’t pay the whiskey tax had to appear in federal court. In western Pennsylvania, the closest federal courthouse was 300 miles away in Philadelphia.

While eastern distilleries paid the tax, benefiting from lower tax rates for large producers and the ability to pass the tax on to consumers, farmers in the west buckled under the law’s requirements.

Many simply refused to pay. But others took a more violent approach.

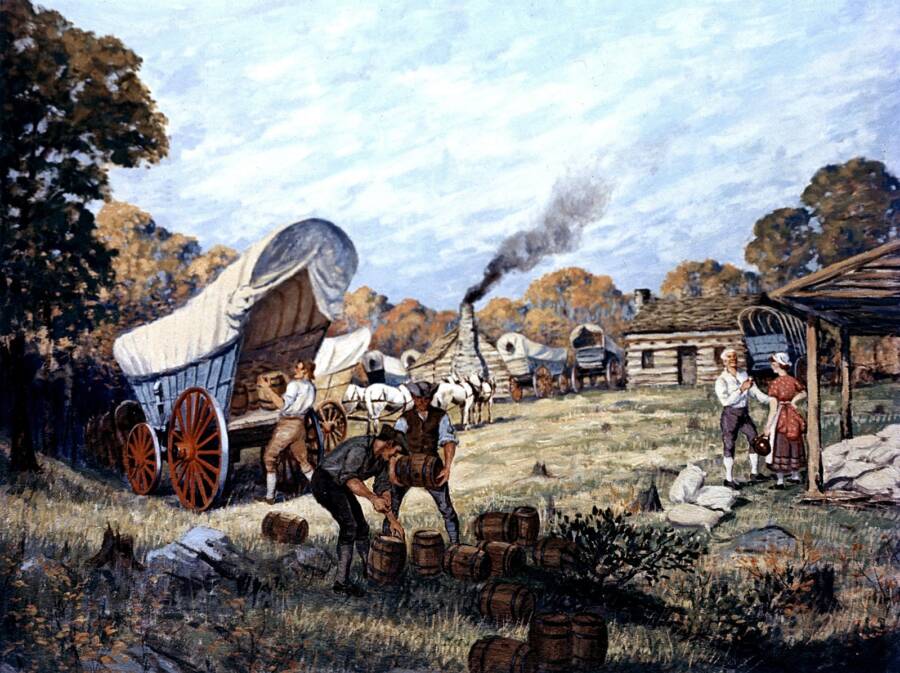

Carl Rakeman/Federal Highway AdministrationWestern Pennsylvania settlers making whiskey on the frontier.

When the government sent tax collectors to the frontier, they faced violent resistance. A group of men dressed as women attacked Robert Johnson, a federal excise officer, on Sept. 11, 1791. They stripped off Johnson’s clothes and tarred and feathered him, abandoning him in the woods.

When Johnson complained and the local government issued arrests, a mob also tarred and feathered the man serving the warrant.

On Sept. 15, 1792, President George Washington took action. With violence simmering on the frontier, Washington denounced anyone interfering with the “operation of the laws of the United States for raising revenue upon spirits distilled within the same.”

The Whiskey Rebellion Heated Up In 1794

With frontier farmers still defying the whiskey tax, the federal government stepped up enforcement. In the summer of 1794, U.S. Marshal David Lennon rode west to confront 60 distillers who hadn’t paid their taxes.

But armed mobs met the marshal and attacked any locals who aided him. In multiple standoffs, both sides fired shots and killed several people. On July 17, 1794, a mob of 700 people attacked the home of a revenue collector, opening fire on the house and then burning it to the ground.

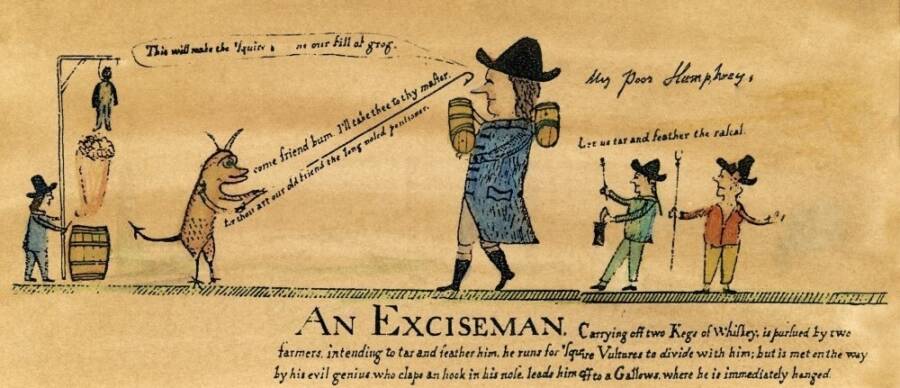

Wikimedia CommonsA 1791 sketch showing two farmers chasing an excise man to the gallows.

David Bradford, the local deputy county attorney, rallied the rebels for an attack on Pittsburgh. When 7,000 angry rioters showed up, the city sent out multiple barrels of whiskey as a gift to calm down the rebellion.

George Washington And The Federal Response

The Whiskey Rebellion represented a major threat against the federal government. If citizens decided they didn’t need to pay taxes, the government’s debt crisis would worsen. But even more critically, the rebels defied federal authority, threatening to undermine the newly formed system.

President Washington tread carefully in his response. Only a decade after the end of the American Revolution, many citizens still worried about tyranny. Yet with anti-tax meetings springing up across western Pennsylvania and federal officers facing deadly attacks, Washington had to act.

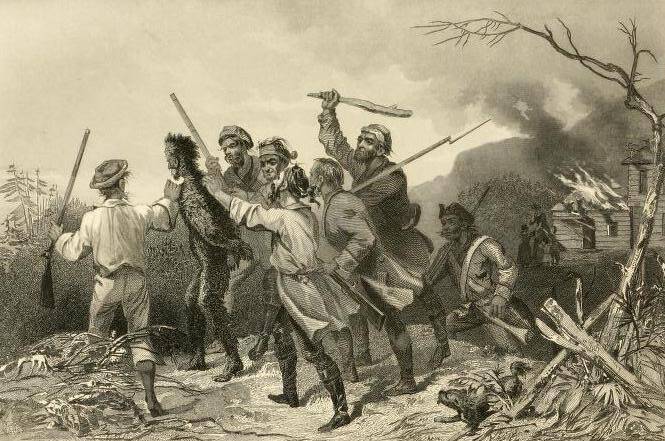

John Rogers/Wikimedia CommonsA 19th-century engraving showing a mob tarring and feathering an excise officer.

On Aug. 26, 1794, Washington wrote to Virginia’s governor, Henry Lee, father of future Confederate commander, Robert E. Lee. The “insurgents” left him no choice, Washington lamented. If he didn’t act, they would “shake the government to its foundation.”

Washington called up a militia of 13,000 men, a force larger than the army he’d commanded at the Battle of Yorktown.

When negotiations with the rebel leaders failed in September 1794, federal commissioners declared it was “absolutely necessary that the civil authority should be aided by a military force in order to secure a due execution of the laws.”

Washington proclaimed that “a small portion of the United States” could not “dictate to the whole union.”

On Sept. 19, 1794, Washington mounted his horse and led troops on a month-long march across the Allegheny Mountains to confront the rebels. He then handed over the force to Henry Lee and Alexander Hamilton.

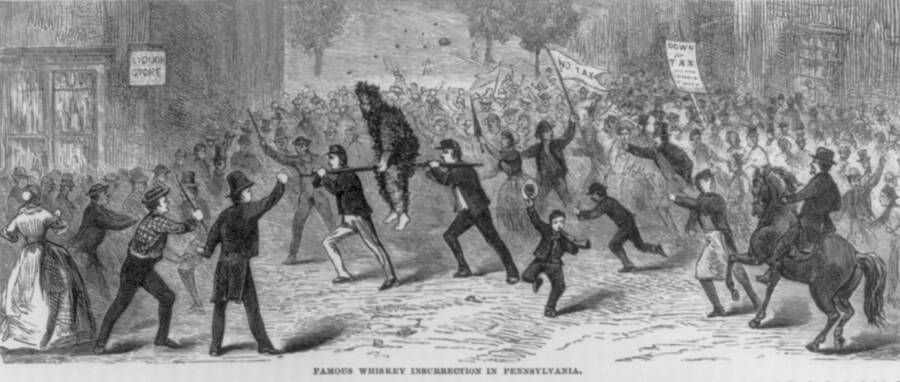

Library of CongressThe Whiskey Rebellion was so violent that the federal government was forced to respond.

The militia marched toward western Pennsylvania to bring the offenders to justice. When the military force reached the heart of the Whiskey Rebellion in October 1794, they arrested 150 rebels and disbursed the rest.

Governor Lee eventually pardoned all but 33 men who had participated “in the wicked and unhappy tumults and disturbances lately existing.”

The Legacy Of The Whiskey Rebellion

A federal regiment occupied western Pennsylvania for months after the Whiskey Rebellion. The government eventually put several rebel leaders on trial and convicted two of treason, though Washington pardoned them in 1795.

The challenge to federal authority shaped the U.S., encouraging some divide in the young republic. For example, Thomas Jefferson saw Washington’s actions as an abuse of power, siding instead with the rural farmers.

Violent resistance to the whiskey tax evaporated, but frontier farmers continued to protest federal overreach. They helped elect Thomas Jefferson to the presidency in 1800, and in 1802 Congress repealed the whiskey tax. For years, the federal government halted all federal taxes on citizens and raised money solely through tariffs.

The Whiskey Rebellion represented a major threat to George Washington’s presidency. But Washington’s ability to repress an uprising on the frontier bolstered federal authority – even as the rebellion fomented divisions that would continue to roil the country to the present day.

After reading about the Whiskey Rebellion, learn more about George Washington’s last days and his agonizing death. Then read about Thomas Jefferson’s dark side.