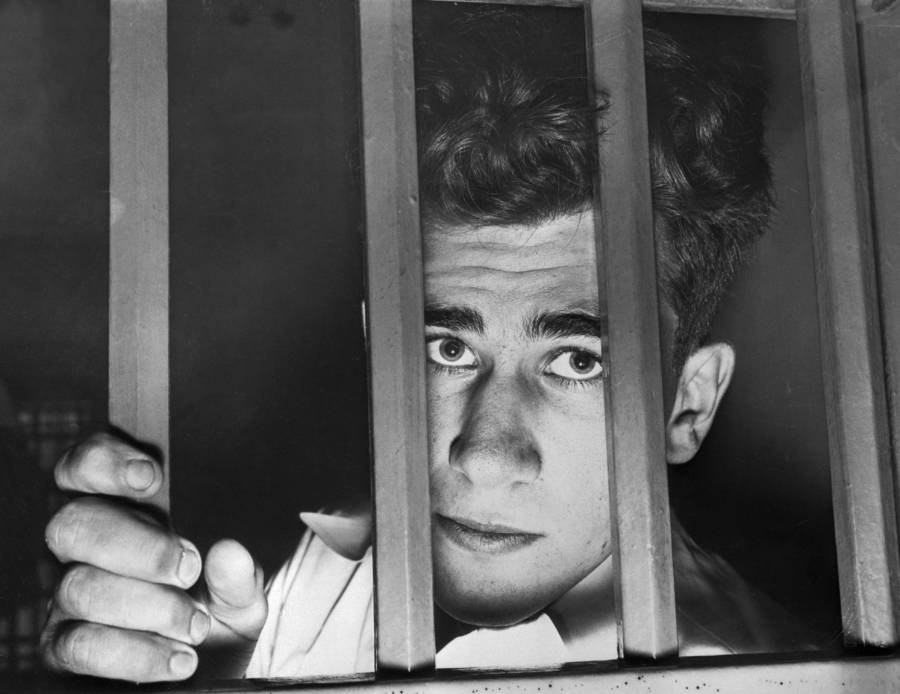

As a teenager, "Lipstick Killer" William Heirens was sentenced to life in prison for a series of grisly murders he'd allegedly committed on Chicago’s North Side — but many believe he was innocent.

Getty ImagesAllegedly the “Lipstick Killer,” William Heirens was one of the longest-serving inmates in U.S. history.

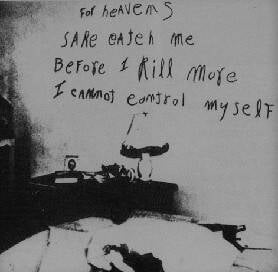

On Dec. 11, 1945, 32-year-old Frances Brown was discovered savagely murdered in her apartment at the Pine Grove Hotel on Chicago’s North Side, a bread knife lodged in her neck. Scrawled on her living room wall in Brown’s own lipstick was a chilling message: “For heaven’s Sake, catch me Before I kill more I can not control myself.”

Before long, two other North Side murders would be linked to the so-called “Lipstick Killer.” As the media went into a frenzy over the sensational case, the police became increasingly desperate to catch the killer. And when a 17-year-old boy named William Heirens was caught breaking into a home on the North Side, it seemed as though they’d found the culprit at last.

But while William Heirens was ultimately convicted of all three “Lipstick Killer” murders and sentenced to life in prison, many believe the investigation was mishandled — and that Heirens spent 65 years behind bars despite being an innocent man.

William Heirens’ Early Life Of Crime In Chicago

As a young boy, William George Heirens gave no indication that he would grow up to become a vicious murderer. He had no prior record of violence — though he did have a talent for theft.

Born in Evanston, Illinois on the eve of the Great Depression in 1928, William Heirens grew up in a tense, poverty-stricken household. To escape his parents’ arguing, Heirens took to wandering the streets, searching for some relief from the stress of his home life.

He finally found that relief at the age of 12 when, while working at a grocery store, Heirens accidentally shortchanged himself with a customer. To make up for it, he stole a single dollar bill from an apartment by reaching through the crack in a chained door.

This small act of petty theft ignited something inside of Heirens, and from there, he graduated to stealing larger sums, as well as personal items. He soon found himself with a small collection of pilfered objects that ranged from the expensive to the mundane, including cameras, cocktail shakers, guns, and even handkerchiefs and undergarments. According to a 1948 psychiatric study, he later told his parents his theft was a “troubling habit,” something he found strangely exciting.

This habit finally got William Heirens into trouble when at 13, he was arrested for breaking into a local apartment basement. He was eventually sent to a semi-correctional boys’ school in Indiana. However, his time there apparently proved fruitless, as he was arrested again the following summer. This time, the court recommended Heirens be sent to a private institute in central Illinois.

While ineffective at curbing his crime streak, these schools were good for one thing: At both institutions, Heirens proved to be an impeccable student. His grades were so good, in fact, that at the age of 16 he qualified for courses at the University of Chicago as part of a gifted students program. He enrolled there as a bachelor student at the age of 17 and was reportedly hoping to become an electrical engineer one day.

Public DomainThe note found scrawled in Frances Brown’s lipstick at the scene of her murder.

While at the university, Heirens was actively involved in extracurricular activities like dance and chess. He was good-looking and well-liked, and even had a string of girlfriends.

But apparently, none of that could stop William Heirens from reverting to his old childhood “habit.” And soon, that habit would allegedly evolve into something far more sinister.

The Lipstick Killer Terrorizes Chicago’s North Side

Though the murder of Frances Brown was the most well-known of William Heirens’ supposed crimes due to its sensational nature, it was actually the second murder committed by the so-called “Lipstick Killer.”

The first came six months prior — and it didn’t even make the front page of local papers.

On June 5, 1945, 43-year-old Josephine Ross had been found in her home, dead from multiple stab wounds to the neck. A skirt had been wrapped around her neck, and her wounds had been taped shut. Her home had been ransacked, but nothing appeared to have been taken. And while police reportedly found no fingerprints at the scene, they did find a few dark hairs clutched in Ross’ hand, leading the police to guess they were looking for a dark-haired suspect.

With few leads to go off of, it seemed that the Ross murder would go unsolved — that is, until six months later, when William Heirens allegedly committed his second murder.

In December 1945, Frances Brown’s naked body was discovered in the bathroom. Brown’s head was wrapped in cloth as Ross’ had been. Once again, there was a startling lack of evidence, and very little appeared to have been stolen. The police found no fingerprints in the apartment, and no further hint as to who the murderer might have been.

There was, however, one glaring clue left for the police: the strange message scrawled on the living room wall in Brown’s own red lipstick.

The Brutal Murder Of Suzanne Degnan

Local newspapers immediately picked up the story of Frances Brown’s murder, splashing photos of the lipstick message across their front pages and branding the culprit “The Lipstick Killer” — a nameless, faceless villain on a silent rampage through Chicago’s affluent North Side. In the weeks that followed, the city was held in a state of terror, waiting with bated breath for the next horrific crime scene to be discovered.

They didn’t have to wait long.

Public DomainSuzanne Degnan, the six-year-old murdered by the Lipstick Killer, allegedly William Heirens.

Around 7:30 on the morning of Jan. 7, 1946, a man named James Degnan discovered that his six-year-old daughter Suzanne was missing from her bedroom. Police swarmed the home and immediately began a search of the Degnans’ North Side neighborhood.

Investigators soon discovered a crumpled ransom note in Suzanne’s room demanding $20,000 in exchange for her safe return. It also instructed the Degnans not to involve the police, and claimed more orders would follow. But as police intensified their search, they discovered that the ransom note was nothing more than a ruse.

At around 7 p.m. that evening, Suzanne Degnan’s severed head was found floating in a sewer basin near the Degnan home. The ribbons that had been tied in her hair that morning were still in place. Before long, her legs and torso were also discovered in nearby sewers.

Once again, Chicago was caught up in a sensational crime. And as the public responded to Suzanne Degnan’s murder with fear and outrage, pressure was mounting on the Chicago police to catch the person responsible.

For months, they investigated the Degnan murder, questioning hundreds of people. But after making a few arrests and still failing to solve the case, the police were getting desperate.

William Heirens Becomes The Suspect In The North Side Killings

On June 26, 1946, William Heirens was planning to take his girlfriend on a date. He just needed some extra cash.

Heirens claimed he had originally planned to cash a $1,000 savings bond at the post office. Knowing he’d be carrying a large amount of cash that night, he decided to carry a revolver with him. However, the post office was closed when he arrived — so once again, Heirens went back to his old habit.

He stopped by an apartment building in the same affluent neighborhood where Suzanne Degnan once lived, and reached into an open apartment door.

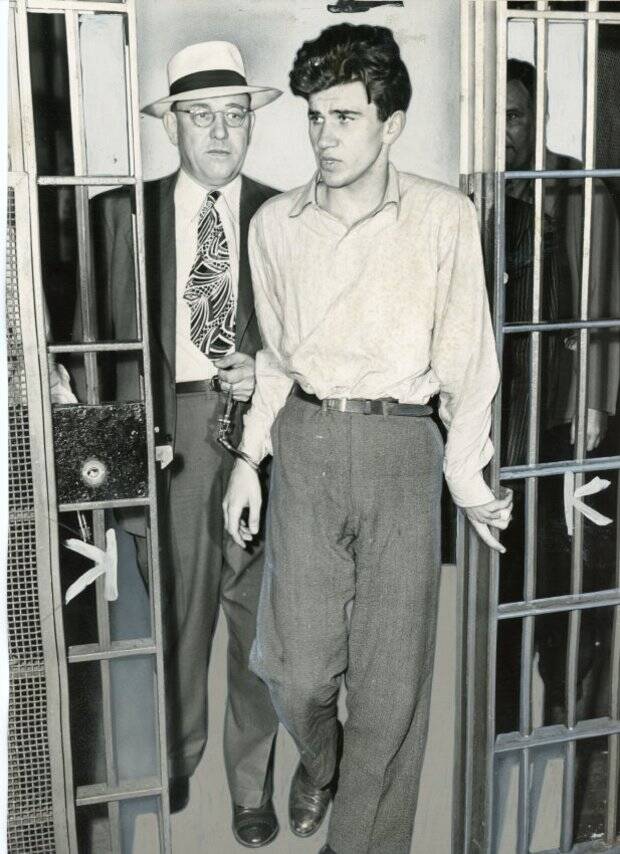

Unfortunately for William Heirens, a tenant spotted him before he got the chance to take anything. As Heirens fled the scene, he was chased by two policemen. Cornered, the 17-year-old pulled out his gun.

Heirens and the officers gave conflicting accounts of what happened after that. According to the officers, Heirens shot at them, forcing them to fire their own guns back at him. Heirens, meanwhile, claimed that the police shot first.

Whatever the case, shots were fired; frightened, Heirens leapt at the officers and held one of them down. This struggle finally culminated in an almost comical apprehension: an off-duty police officer, still in his swim trunks from a day at the beach, arrived at the scene and smashed a stack of flower pots over Heirens’ head, rendering him unconscious.

And as bad as things looked for William Heirens, they were about to get far worse.

Edgewater Historical SocietyWilliam Heirens was subjected to days of torture before he pleaded guilty to the murders.

After having his head stitched up, Heirens was transported to the hospital wing of the Cook County Jail. Meanwhile, the police searched Heirens’ room at the university, his parents’ home, and a locker he kept at a local train station, all without a warrant.

In the locker, they found evidence of his lifetime habit of thievery. And after taking his fingerprints, they purportedly discovered that they matched those found on the Degnan ransom note — a fact that would later be disputed.

The Torture Of William Heirens By Chicago Police

The authorities were determined to prove William Heirens was the Lipstick Killer. So over the next few days, they subjected him to a torturous interrogation to draw a confession out of him. As he lay recovering from his injuries, they denied him food and sleep, isolated him from his parents, and prevented him from seeing an attorney.

During one interrogation session, a nurse poured ether on Heirens’ genitals while he was strapped to a hospital bed. During another, a police officer repeatedly punched him in the stomach. Officers continually chanted details from the Degnan murder in an effort to spark recognition in Heirens.

Throughout his excruciating ordeal, the 17-year-old slipped in and out of consciousness due to pain, drugs, and exhaustion. And still, Heirens would not confess to the murders.

Five days into his interrogation, a doctor gave William Heirens a spinal tap without anesthetic. Per court documents, a polygraph was ordered immediately after, but Heirens was in too much pain for an accurate reading to be assessed.

At another point, a doctor injected Heirens with sodium pentothal, or “truth serum,” without gaining Heirens’ consent or the consent of his parents. The drug put the teen in a state of delirium.

Under its effects, hovering somewhere between excruciating pain and unconsciousness, Heirens allegedly began to mutter the beginnings of a confession, suggesting that a man named “George” could potentially have committed the murders.

Police determined that “George” was Heirens’ alter ego, and decided to take this as an admission of guilt. And when the press got wind of “George,” they declared Heirens to be a dangerous “Jekyll and Hyde” character with a split personality.

Before William Heirens had a chance to present his case in court, the city had all but determined he was guilty.

Was William Heirens Really The Lipstick Killer?

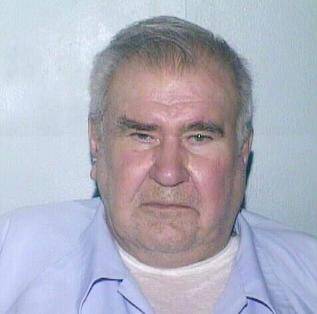

Illinois Department of CorrectionsWilliam Heirens spent most of his life behind bars.

While the police claimed to the press that the evidence was stacked against William Heirens, the truth is far more complicated.

The police claimed that Heirens’ fingerprints matched those found on the ransom note left in the Degnan home. However, investigators found only nine points of comparison between Heirens’ fingerprints and those on the note, when the FBI standard to definitively declare a match was 12 points.

What’s more, police claimed they had uncovered additional prints on the ransom note that matched Heirens’. Somehow, no one had noticed these prints until after Heirens’ arrest — despite the note having been thoroughly examined over a period of months before then and handled by multiple individuals.

Over the years, multiple handwriting experts have also independently determined that William Heirens’ handwriting did not match the note left on Frances Brown’s wall or the ransom note left in the Degnan home.

On July 12, 1946, 17 days after his arrest, Heirens was indicted for assault with intent to kill, robbery, 23 counts of burglary, and three counts of murder. Though he insisted he was innocent, Heirens ultimately agreed to a plea deal to escape the electric chair.

“The thing is, once you’re dead, there’s no clearing things up,” he told GQ in a 2008 interview. “When you’re alive, you still have a chance to prove that you weren’t guilty. So I was better off being alive than being dead.”

Heirens pleaded guilty to all three murder charges and was sentenced to three consecutive life terms in prison. His decision may have saved him from the chair, but it ended up costing him the rest of his life: Heirens spent the next 65 years in prison, including 30 years in maximum security.

William Heirens would maintain his innocence up until the day he died behind bars at age 83. When he died, he was Chicago’s longest-serving inmate.

After reading about the William Heirens, the alleged Lipstick Killer, read about the chilling unsolved case of the Chicago Strangler. Then, read about Leopold and Loeb, the rich Chicago teens who plotted the “perfect” murder.