The Wineville Chicken Coop Murders rocked a small southern California town in the late 1920s – and led to the hanging of Gordon Northcott.

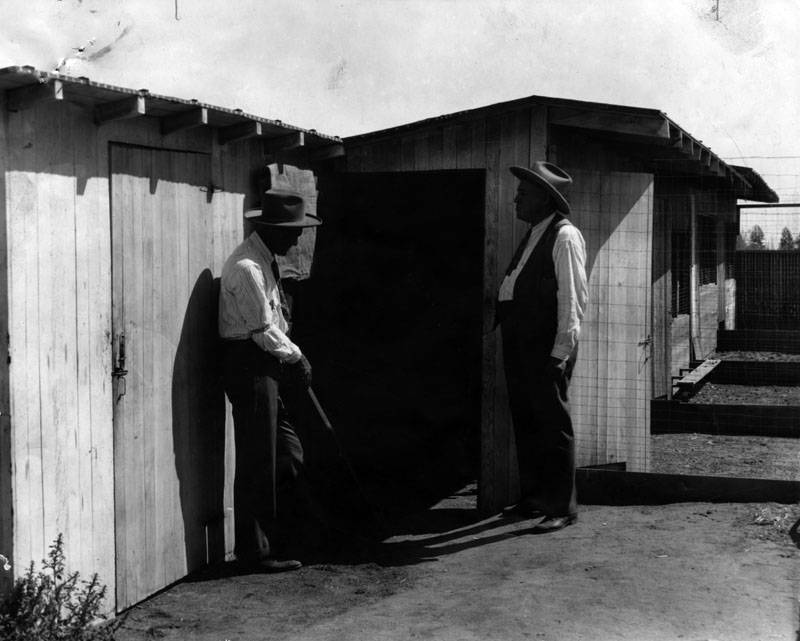

Policemen at the “murder ranch” in Wineville.

You won’t find Wineville, California anywhere on a map. The southern California town certainly existed, although it abruptly “vanished” in 1930, replaced suddenly by Mira Loma. What had happened was the Wineville Chicken Coop Murders – crimes so heinous that the townspeople couldn’t bear to be associated with “Wineville” any longer.

The case of the Wineville Chicken Coop Murders is filled with so many bizarre twists, turns, and testimonies that even J. Michael Straczynski, screenwriter for Changeling (which was loosely based around the events of the murder), could hardly believe it was true. After reading the story in the Los Angeles city archives, he figured, “This can’t be real… This has to be a mistake.”

The murders of several young boys (the true number of victims is still unknown) in southern California from 1926 to 1928 captivated and disgusted the nation, generating such an extreme amount of negative publicity that the town where they had occurred took the drastic step of changing its name afterwards.

The gruesome crimes first came to light in 1928, when police found the headless body of a male teenager in a ditch. The case might have remained unsolved and forgotten had the authorities not received a strange phone call from the United States consul in Canada that set off an incredible series of events.

The consul had been tipped off about the Chicken Coop Murders by 19-year old Jessie Clark, who had returned to the country in a panic after a visit to her brother in California. Fifteen-year-old Sanford Clark had been working on the chicken ranch of his 19-year old cousin, Gordon Stewart Northcott.

Jessie had been concerned that something seemed strange about her brother’s letters and made a trip down to visit him. Despite Northcott’s efforts to make sure the siblings were never alone together, Jessie managed to wheedle the truth out of her brother: their cousin had not only been sexually abusing him, but was also a murderer.

Sanford asked his sister if she had recalled “reading in the papers about a little boy that was kidnapped” named Walter Collins.

Collins had vanished in March of 1928 on his way to see a movie. Sanford then went on to say Gordon Northcott “had kept Walter at the ranch for a little over a week and had killed the boy when people started searching for him.” He also told his sister about the murders of two other boys as well as a Mexican ranch-hand Stewart had shot and decapitated.

A terrified Jessie fled back to Canada and told the American consul the whole story, who alerted the Los Angeles Police Department. Although Gordon Northcott and his mother Sarah Louise Northcott tried to flee, they were apprehended in Canada and were extradited to the United States for trial. In the meantime, police at the ranch were finding human remains buried in limestone beneath the chicken coop.

Los Angeles Public LibraryThe chicken coop on the ranch after it was excavated for evidence.

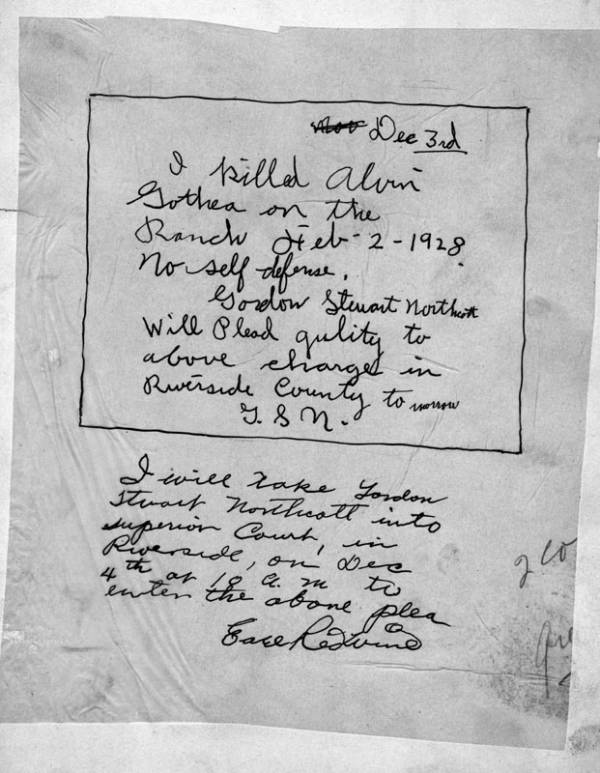

Northcott confessed to only one murder: that of the Mexican teenage ranch-hand, Alvin Gothea, believed to be the boy the police had found in the sack. In a desperate attempt to protect her son, Northcott’s mother claimed to have killed young Walter Collins (whose body was never found).

During the trial, she additionally claimed that her murderous son was the product of an incestuous relationship between her husband and their daughter, though this was never proven.

Los Angeles Public LibraryGordon Northcott only confessed to one murder.

Gordon Northcott was found guilty of the murders of three of the boys, sentenced to death, and hanged in 1930. His mother was found guilty of murdering Walter Collins and given a life sentence, but the strange story of the Chicken Coop Murders did not end there.

Although Walter had disappeared in March of 1928, in August of that year another boy claiming to be Walter appeared in Illinois.

After paying for his travel expenses, Christine Collins (Walter’s mother) went back to the LAPD claiming this stranger was not her son. At that point, the police were under enormous pressure to solve the kidnapping, and Captain J.J. Jones, who was heading the investigation, was less than thrilled that the case was reopened.

Los Angeles Public LibraryThe true number of boys Gordon Northcott sexually abused and murdered is still unknown.

Although Walter Collins’s dental records proved that this new boy was indeed an impostor, the LAPD tried to rid themselves of the inconvenience of a grieving mother by having Christine committed to a psychiatric ward.

By this time, her story had garnered tremendous media attention and when she was released from the hospital five days later, the public had rallied around her. The imposter would later confess he was not Walter Collins but had only impersonated him because he “wanted to get into the movies in Hollywood.”

By that time, it was too late for her son. Although Jones was suspended and a judge awarded Collins more than $10,000, the Northcotts claimed that Walter was long dead. Collins’ story would inspire the Clint Eastwood film Lizzie Borden murders. Then check out the story of serial killer Edmund Kemper, whose deeds are almost to gross to be real.