From powerful priestesses to demonic masters of the occult, the history of witches is a story of the dangers of being a woman in a male dominated world.

A fearsome being of fairytale and myth, the witch has carved out a home in nearly every culture across the world and time. Indeed, the witch represents the dark side of the female presence: she has power that cannot be controlled.

While the witch often conjures depictions of aging, ugly, hook-nosed women hunched over their cauldrons and inflicting toil and trouble on the masses, history tells us that the witch’s origins are far less sinister. In fact, those whom we consider to be witches were once healers and hallowed members of their communities.

The History Of Witches Dates Back To Biblical Times

According to Carole Fontaine, an internationally recognized American biblical scholar, the idea of the witch has been around as long as humanity has tried to deal with disease and avert disaster.

Wikimedia CommonsA painting in the Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, condemning witchcraft and traditional folk magic.

In the Middle East, ancient civilizations not only worshipped powerful female deities, but it was often women who practiced the holiest of rituals. Trained in the sacred arts, these priestesses became known as wise women, and may have been some of the earliest manifestations of what we now recognize as the witch.

These wise women made house calls, delivered babies, dealt with infertility, and cured impotence. According to Fontaine, “What’s interesting about them is that they are so clearly understood to be positive figures in their society. No king could be without their counsel, no army could recover from a defeat without their ritual activity, no baby could be born without their presence.”

So how did the benevolent image of a wise woman transform into the malevolent figure of the witch we know today?

Some scholars have maintained that the answer may be linked to events long before the birth of Christ, when Indo-Europeans expanded westward, bringing with them a warrior culture that valued aggression and male Gods of War, which then dominated the once-revered female deities.

Others believe that when the Hebrews settled in Canaan 1300 years before the common era, their male-centric — and monotheistic — view of creation came along for the ride. Obeying laws of the Bible, Hebrews believed witchcraft to be dangerous, and prohibited it as a pagan practice.

Christianity Transforms The Witch Into A Figure Of Evil

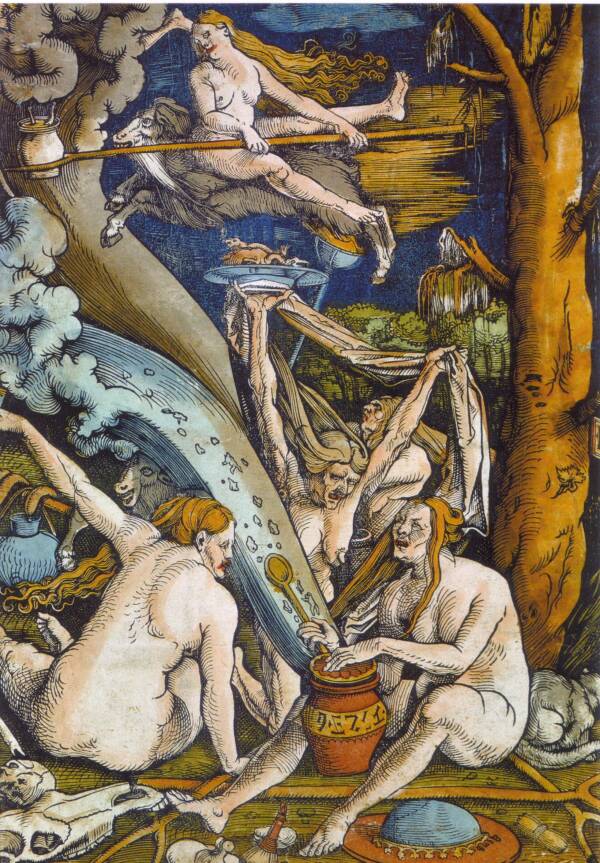

Wikimedia CommonsA 16th-century woodcut of witches as malevolent beings tinkering away in the woods.

Centuries later, this fear of witches spread to Europe. In the 1300s, when the plague decimated Europe by killing one in three people, it also brought with it great fear.

Amid the panic, many attributed their misfortune to the Devil himself — and his supposed worshipers. At this point, the Catholic Church’s Inquisition, which had already been established for decades, expanded its efforts to seek out and punish the non-Catholic causes of the mass deaths, including Devil-doting witches.

These women were believed to worship in large nocturnal assemblies, where various social ills were performed, such as promiscuous sex, naked dancing, and gluttonous feasting on the flesh of human infants. At the climax of this festival, people at the time believed that the Devil himself would appear and participate in an unbridled orgy with all attendants.

In order to save the Church and its followers from the Devil, then, these women had to be tamed. It is with that in mind that Catholic Church inquisitors Jacob Springer and Henrik Kramer wrote the Malleus Maleficarum, a book which assisted witch hunters in the gruesome task of diagnosing and punishing so-called witches, who as women were sexually vulnerable and therefore easy prey for the Devil.

“What else is a woman but a foe to friendship?” wrote the monks. “They are evil, lecherous, vein, and lustful. All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is, in women, insatiable.”

The manual’s vivid descriptions would serve as a platform for zealous witch hunters to act on their prejudices for over 200 years. At the time, Malleus Maleficarum was second to the Bible in terms of popularity.

Fontaine notes that while there had been witch hunting manuals prior to the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum, this particular book was the first to associate a specific gender with witchcraft.

Witch Hunts Become An Instrument Of Misogyny

Wikimedia CommonsExamination of a Witch, by T. H. Matteson, 1853. This work was inspired by the Salem Witch Trials.

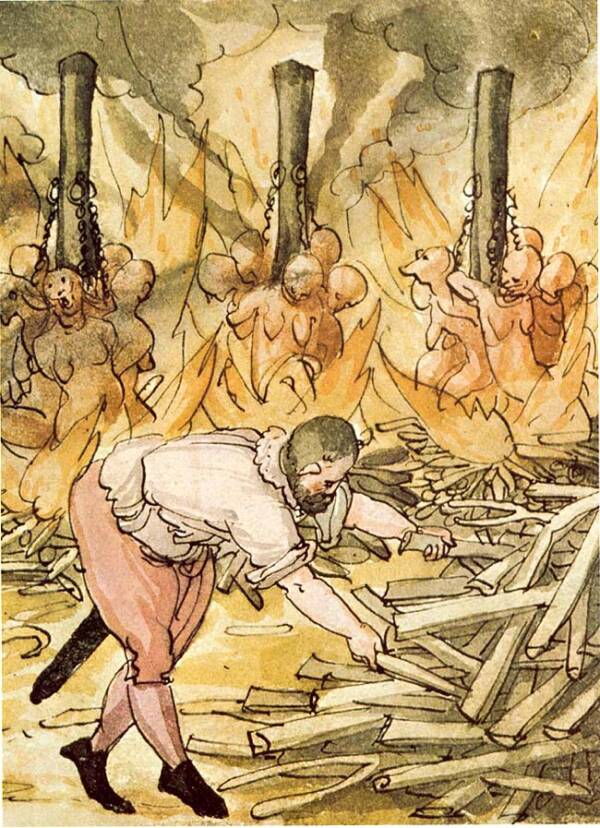

By the end of the 1600s, the witch hunting hysteria in Europe reached its peak. Witch hunts spread like wildfire across Europe, the worst of which occurred in France and Germany. Würzburg, Germany was home to the worst instance of witch hunting: the magistrates of the time determined that most of the town was possessed by the Devil, and condemned hundreds of innocent women to death.

Religion professor Barbara McGraw noted in a 1996 interview that there were some towns in Germany where there were no women left.

Thousands were arrested and brought to inquisitors for examination. Under an inquisitor’s brutal scrutiny, the accused were stripped and searched. Any “suspicious” wart, mole, or birthmark could be enough to receive a death sentence.

In order to execute the accused, however, the women first needed to confess. Torture seemed to be the best way of inciting a confession, and the Church would use instruments such as thumb and leg screws, head clamps, and the iron maiden to generate the “truth” they needed to enact death.

Wikimedia CommonsA late 16th-century depiction of witches being burned at the stake.

While torturing women under examination, the Malleus Maleficarum warned the torturer not to make eye contact with her, as her “evil powers” might cause the torturer to develop feelings of compassion.

When this period ended at approximately the beginning of the 18th century, an estimated 60,000 people in Europe had been killed as witches.

Witch Hunts Sweep America

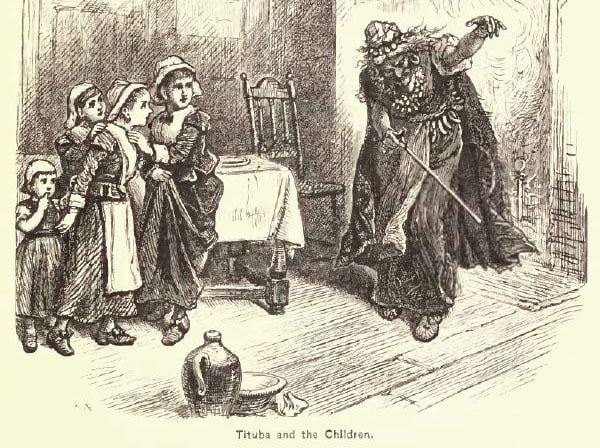

Wikimedia CommonsA 19th- century representation of Tituba the enslaved American witch, by Alfred Fredericks.

Overseas, the most anthologized witch hunt took place in Salem, Massachusetts. The 17th-century settlement had a rough beginning: decades of wars with the Native Americans, land disputes, deep religious divisions, and a tendency to look to the supernatural in order to explain the unknown helped set the grounds for this particularly “New World” brand of hysteria.

The Salem witch trials began in 1692, in the home of a Puritan minister named Samuel Parris. Parris was deeply concerned about a game his daughter Elizabeth and his niece Abigail had played, in which the two girls looked into a primitive crystal ball and saw a coffin. This vision sent them into convulsions, and within a few days nine other girls throughout the community were stricken with the same ailment.

Under the pressure of Parris, the girls then named three witches who may have cursed them: Tituba, their household slave; Sarah Good, a beggar woman; and Sarah Osborne, a widow rumored to have had an illicit affair with one of her servants. All three women were social outcasts, and thus easy targets for suspicion.

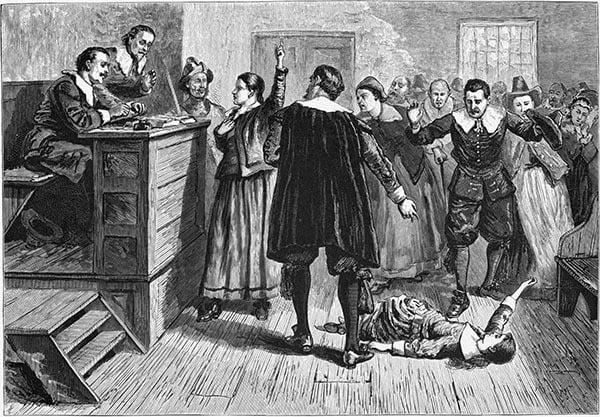

Wikimedia Commons The central figure in this 1876 illustration of the courtroom where the trials were held is usually identified as Mary Walcott.

The hysteria behind the 1692 Salem witch trials spread to 24 outlying villages. That year, jails were crowded with more than 200 accused witches, 27 of whom were found guilty. Nineteen were killed.

The trials met a swift end, however, in part because supposed victims began pointing their fingers at high-ranking figures within the community. When the wife of the governor of Massachusetts was accused of witchcraft, leaders saw to it that the trials ceased immediately.

As to what spurred the girls’ confessions, Fontaine attributes them to a form of social release. The girls had been so tightly controlled in Salem, Fontaine argues, that this confession garnered them some kind of attention.

Witchery Is Revived By Wicca

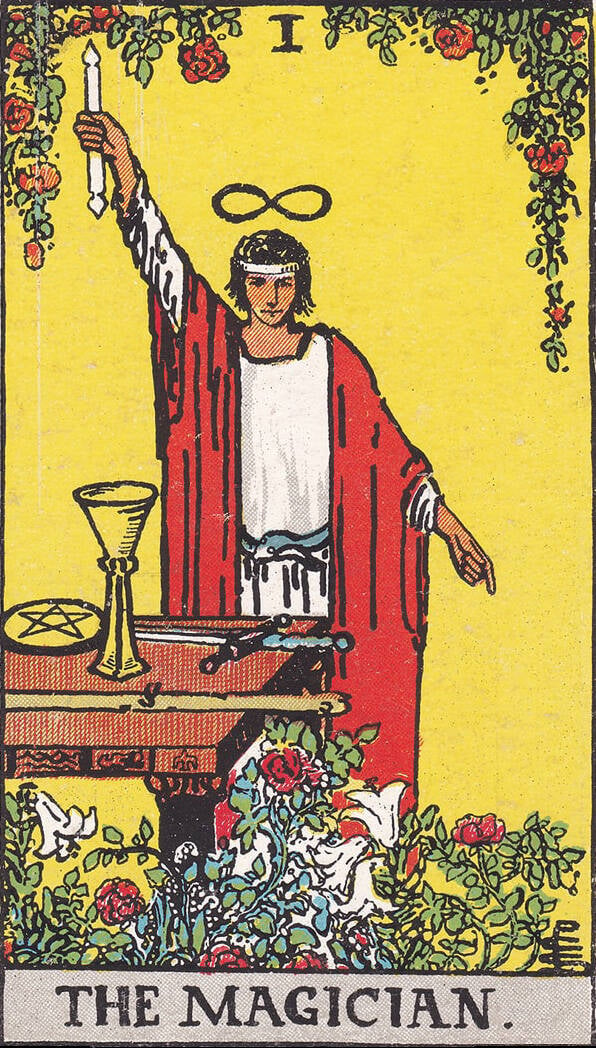

Wikimedia Commons“The Magician” card, from the Waite-Smith tarot, is depicted using the same tools that modern Wiccans use.

Hundreds of years later, the fearsome image of the witch has faded and been absorbed by a popular culture, which has used the witch’s violent history as costume inspiration. Others, however, have used the history of witches to found a new spiritual movement.

In 1921, British archaeologist Margaret Murray penned a book called The Witch Cult in Western Europe, in which she argued that witchcraft had not been an obscure occult, but rather a dominant religious force.

Though Murray’s theories have been widely discredited since the book’s publishing, her work sparked a fascination with witches that had been dormant for 300 years, which eventually spawned the Wicca religion.

Wicca, which is named after an Anglo Saxon term for “craft of the wise,” recalls ancient practices that used herbs and other natural elements to promote healing, harmony, love, and wisdom, all following the tenet of “harm none.”

It remains to be seen who the world’s powerful will choose as their next witch — but as history has shown, the feared is often female.

Next up, read about the most painful medieval torture devices. Then, discover the Basque Country witch trials, the worst witch hunt in history.