The study suggests that the dietary wellbeing of Wrangel Island's mammoths was stable and that all long-term weather events had already passed. The culprit of their demise, it claims, were short-term "icing events."

Wikimedia CommonsA painting in Canada’s Royal Victoria Museum depicting an adult woolly mammoth.

After most of Earth’s woolly mammoths died out, one population carried on a remote Arctic island. The final holdouts survived on Wrangel Island and outlived their mainland counterparts by 7,000 years. Finally, about 4,000 years ago, that lone group went extinct too.

Now, scientists have learned more about these last mammoths and the “catastrophic” event that ended their species.

According to Newsweek, Laura Arppe from the Finnish Museum of Natural History and her colleagues studied the population’s diet, nutrition, and metabolism by using mammoth bones and teeth found on Wrangel Island and comparing them with other populations.

By analyzing their carbon and nitrogen isotopes — which clarify the nutrition and metabolic functioning of the animals in the thousands of years preceding extinction — Arppe’s team was able to garner a clearer picture.

Published in the Quaternary Science Reviews journal, their research indicates the species wasn’t under direct pressure, but that a powerful weather event led to their starvation and subsequent extinction, instead.

A 2017 study published in PLOS found that a “genomic meltdown” was responsible for their disappearance, with mutations resulting from their dwindling population size contributing to their downfall. With no ability to synthesize proteins, it claimed, the mammoths’ loss of smell and ability to detect pheromones rendered them unable to socialize, procreate, and thrive.

This latest research, however, found no evidence of a shrinking population size before extinction and that a seemingly far simpler scenario was the culprit: the weather.

Juha KarhuThe study used woolly mammoth teeth and bones found on Wrangel Island, like this set of enormous chewers found on the remote Arctic island.

Previous studies argued that the climate change following the last ice age, alongside human hunting, led to the extinction of the woolly mammoth. According to The New York Times, the last surviving populations lived on the two remote islands of Wrangel and St. Paul.

While St. Paul’s woolly mammoths lived until about 5,600 years ago, the mammoths on Wrangel Island survived 1,600 years longer. The 2017 study analyzed the entire genomes of two mammoths: one from Siberia that died 45,000 years ago and one from Wrangel Island that died 4,300 years ago.

They were able to asses the population sizes of both eras by studying the genetic variation in each genome and found the Siberian mammoth lived alongside 13,000 mammoths, while the Wrangel mammoth was alive alongside a mere 300.

Arppe’s research, however, began with the animals’ dietary wellbeing in order to assess a potential lack of resources — and the supposed subsequent population decrease. They found no evidence of any “alarming long-term changes” in habitat or climate in the Wrangel Island mammoths.

“No one had looked at what was going on with the dietary ecology of the Wrangelian mammoths, and with all these other observations related to diet, it was high time to do so,” said Arppe.

“We wanted to look at the dietary ecology of the mammoths in order to see if we could find signs of changes in their diet, nutrition or metabolism leading up to extinction, e.g. if we could see signs of starvation or malnutrition.”

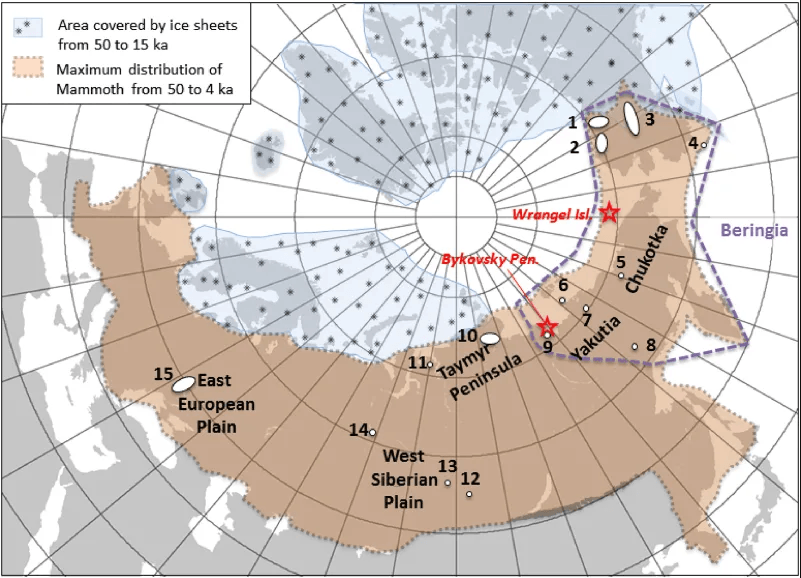

L. Arppe et al., 2019This map shows the locations of mammoth remains used in the study, with 1 ka equalling 1,000 years.

With woolly mammoths in Russia disappearing 15,000 years ago and the population on St. Paul Island vanishing 5,600 years ago, the debate surrounding the extinction of the last group on Wrangel Island has intrigued scientists for years.

“Judged from the numbers of radiocarbon-dated mammoth bone finds on Wrangel Island, this last island population appears to have vanished rather abruptly,” said Arppe. “There [are] no signs of a dwindling population size before extinction. [It’s] kind of like they hit a wall at approximately 4,000 years ago.”

“All the major changes in climate and range size had taken place so long ago: the change to the warm Holocene climate at about 10,000 years ago, the isolation of the island and its reduction to present-day size at about 8,000 years ago.”

“So as judged from what previous proxy studies have shown about their environment, they seem to have disappeared from amidst stable conditions. Why?”

Arppe’s research indicates that “icing events” — when rain on snow causes the ground to become covered in ice and impenetrable to hungry woolly mammoths — to have been the final nail in the coffin.

Wikimedia CommonsThe last surviving population of woolly mammoths died on Wrangel Island approximately 4,000 years ago.

The team found that Wrangel mammoths were fairly comparable to their Siberian counterparts in terms of dietary wellbeing, with one key difference. The former used their fat reserves during cold winters, while the latter did not. This may have led to the Wrangel mammoths’ extended survival.

What did fatally affect them in the end, however, were icing events. “These types of events have been known to cause deaths of large numbers of herbivores in the Arctic,” Arppe explained. “20,000 musk oxen were starved to death in 2003 in the Canadian Arctic due to a rain-on-snow event.”

While the research team concluded that it was this environmental factor that irreversibly affected the species, they also found signs that a lack of healthy freshwater could have played a role.

The 2017 study suggested that it was a lack of quantity that did them in, as woolly mammoths are heavier drinkers than elephants. Arppe’s research indicates the quality of the water, rather, was the problem.

“Our next step is to study these [severe water quality issues] to either reject or confirm the hypothesis, that from time to time, the drinking water supply of the animals had high levels of harmful or even toxic elements released from the local bedrock, that might have affected the population’s fitness.”

After learning about what killed the last surviving population of woolly mammoths on Wrangel Island, read about how elephants migrate to new areas to avoid stress. Then, learn about how conservation efforts are pushing large predators into new territories.