Known for her prowess on the battlefield and her penchant for cross-dressing, Yoshiko Kawashima became a polarizing figure in Asia during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Wikimedia CommonsBorn a princess in China, Yoshiko Kawashima lived most of her life as a spy for Japan.

Yoshiko Kawashima’s life sounds like something out of the movies. Born a Chinese princess at the turn of the 20th-century, she was sent to Japan following the fall of the Qing Dynasty. There, Kawashima grew up to be a cross-dressing spy who dreamed of restoring her family’s former glory. Her flamboyance made her a media darling in Japan; her exploits captured the imagination of millions.

But Kawashima’s fortunes would only last as long as those of the empire she served. To the Japanese, she was an inspiring and romantic hero. But to the Chinese, Kawashima was the worst kind of traitor. Her popularity waned in later years and Japan’s defeat during World War II meant the end for this dashing, nonconforming, princess-spy.

This is the remarkable, true story of Yoshiko Kawashima.

Yoshiko Kawashima: Born Into A Dying Empire

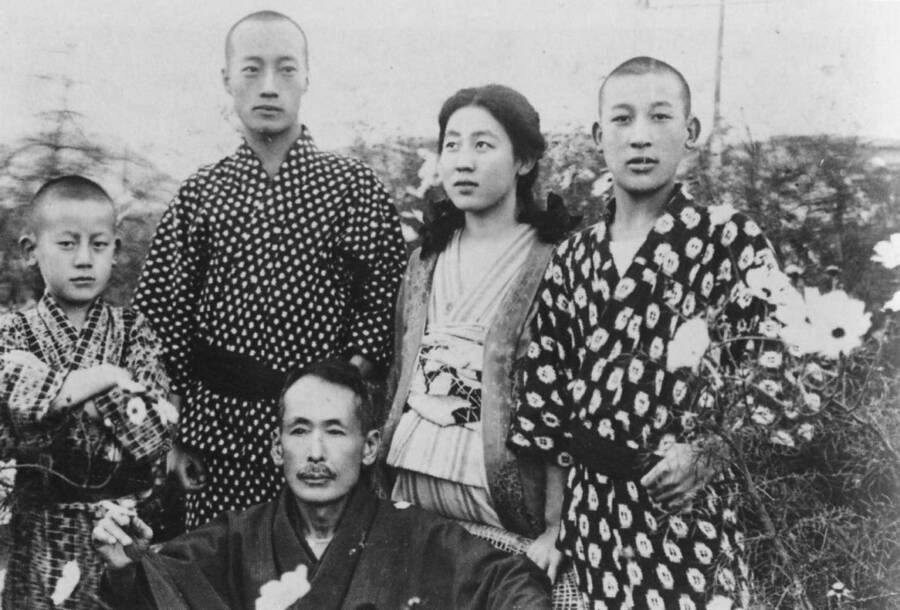

Wikimedia CommonsYoshiko Kawashima with three of her brothers and her adoptive father, Naniwa Kawashima.

Yoshiko Kawashima was born Aisin Gioro Xianyu in about 1907, one of 38 children born to Prince Shanqi, a Manchu prince related to the Qing Dynasty.

The Qing had swept to power in the 17th century as conquerors, nomadic warriors who swiftly toppled the Ming dynasty. For 200 years, the Manchurian emperors had reigned over a prosperous nation. But by the time Kawashima was born, their grip on power was weakening.

In 1911, a revolution led by nationalist reformer Sun Yat-sen overthrew the Qing Dynasty and established the Republic of China. As a result, Kawashima was sent to live with a Japanese friend of her father’s, Naniwa Kawashima. She was likely around the age of eight years old.

Shipped off to Naniwa’s Tokyo mansion, little Aisin Gioro Xianyu was rechristened with the name she would use forever afterward: Yoshiko Kawashima.

A Cross-Dressing Chinese Princess Who Admired Joan of Arc

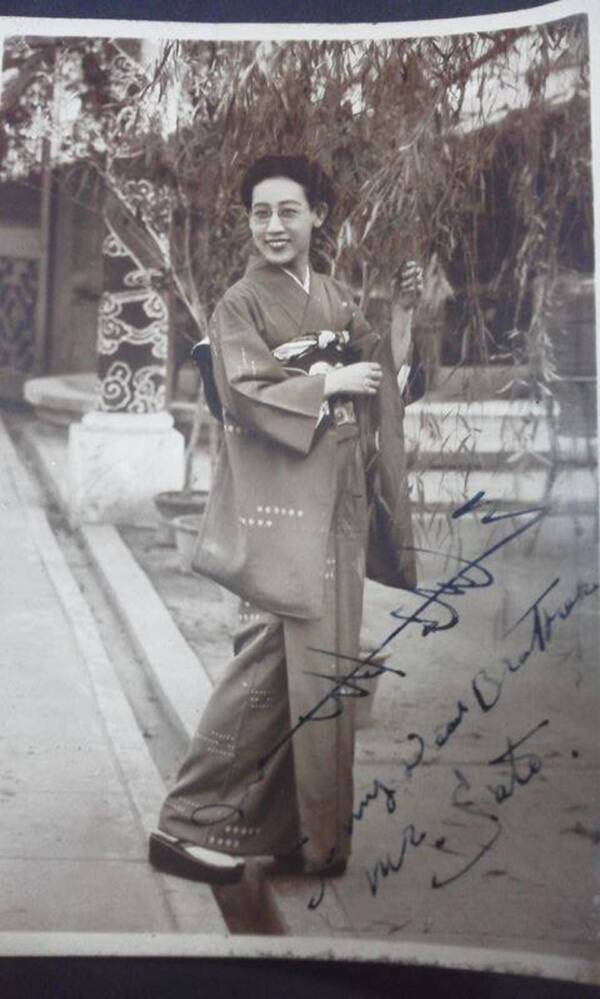

Wikimedia CommonsKawashima wore men’s clothes and rode a horse which she claimed was descended from one of Napoleon’s.

Yoshiko Kawashima, a princess-in-exile, made it clear that she was anything but conventional. She rode a horse to school, took to wearing men’s clothing, and cut her hair first into a stylish bob and then into a buzz-cut, a shocking decision to polite Japanese society.

“I decided to cease being a woman forever,” Kawashima said and suggested that she desired to embody a “third gender”. Such measures were possibly Kawashima’s attempt to escape the suitors that her adoptive father kept close.

She didn’t want to be a bride. Kawashima wanted to be like Joan of Arc — a warrior. The famous French heroine stirred something in Kawashima, who, as a child in school, told her classmates: “If I had three thousand soldiers, I’d take China.”

Her adopted father noted this as well. Although he encouraged Kawashima’s desire to return to China and restore her family’s power, he noted that she “aspires to be like that mannish Joan of Arc.”

In her late teenage years, Kawashima also discovered an enthusiasm for sex, carrying on a string of affairs. These relationships, as well as her scandalous public image — a Chinese princess living in Japan would never escape the attention of the media — led Naniwa to arrange for her marriage to the Mongol prince Ganjuurjab, the son of a rebel leader who’d enjoyed the support of Prince Shanqi.

Kawashima, however, refused to be constrained by marriage. She soon took off for the nightlife of Tokyo before heading to Shanghai, then called “The Paris of the East and the New York of the West”.

By 1931, the 24-year old rebel was without contacts, family, money, or prospects, drifting from dance halls to bars to casinos. With no employment, she had to think of some way to earn her keep.

That’s when she got a call from the Japanese Kwantung Army.

Yoshiko Kawashima’s Path To Becoming A Spy For Japan

Wikimedia CommonsJapanese troops marching into Manchuria in November 1931.

Japan’s Kwantung Army had long had its eyes on Manchuria, viewing the region, which lies next to Korea, as the rightful possession of the Japanese Empire. In 1931, Japanese officers planted a weak bomb under train tracks outside of the city of Shenyang, accusing Chinese saboteurs as a pretext for their invasion of the whole of northeastern China.

Now the Japanese had control of Manchuria — but they needed it to appear legitimate.

Kawashima’s Mongolian and Manchurian connections, as well as her adventurous spirit and skill for disguise, made her an attractive recruit for Japanese military intelligence. She started to work for General Kenji Doihara, known both as “Lawrence of Manchuria” in imitation of British officer T. E. Lawrence, and as the architect of Manchuria’s nightmarish opium industry.

Now that the Japanese plans to set up a Manchurian puppet state were near completion, a pliable imperial figurehead was all they needed. Kawashima persuaded the deposed Qing Emperor Puyi to become the ruler of Manchukuo. Through him, Kawashima achieved her goal — she’d restored the Qing Dynasty to a seat of power.

Manchukuo: Establishing A Japanese Puppet State

Wikimedia CommonsKawashima, left, sits beside Ryukichi Tanaka, right, a Japanese officer with whom she had an affair.

According to Ryukichi Tanaka, a Japanese officer with whom Kawashima carried on a years-long affair, her next exploit was in provoking violent unrest in Shanghai. In the winter of 1932, Tanaka claimed, Kawashima traveled around town paying workers to stage violent riots and brawls. This work gave Japanese troops yet another excuse to strengthen their position in China.

During this time, she also began to play the role of a dashing soldier in Manchukuo. Kawashima led a small army of several thousand irregular cavalry troopers to suppress Chinese resistance fighters.

Japanese officials were eager to use her as a public relations figurehead. By 1933, a popular novel, The Beauty in Men’s Clothing, was written about Kawashima. It presented a fictionalized, exotic account of her activities — creating a haze around the truth of Kawashima’s exploits. Returning on occasion to Japan, she appeared on radio shows and even released an album of Mongolian folk songs.

These activities, as well as her continued leadership of the “anti-bandit force” — about 5,000 soldiers which Kawashima led to protect Puyi — gained her widespread fame in Japan.

Still, Kawashima straddled both her identity as a Chinese princess and a hero in Japan. In one speech, she explained “As commander I have ventured out into the hail of gunfire a number of times, and indeed I have sustained three bullet wounds. But when I think about it, I see that, friend or foe, we are all brothers.”

The End Of Yoshiko Kawashima

Wikimedia CommonsBy 1945, Kawashima was sidelined by the Japanese and placed under house arrest.

By 1940, the romantic figure of the horse-riding Manchu princess was no more. The Japanese military was thoroughly sick of Kawashima, who was too visible to be useful as a spy and too opinionated to be trusted to keep quiet.

By now addicted to morphine and opium and suffering from syphilis, Yoshiki ran a blackmailing racket to extort money from wealthy Chinese citizens before she was placed under house arrest. At one point, General Hayao Tada, rumored to be another of her lovers, even attempted to have her killed, but ultimately transferred her to house arrest in Japan.

In 1941, Kawashima was exhausted, lonely, and adrift. With only her pet monkeys for company, she returned to Japanese-occupied Beijing, where she stayed until the end of World War II.

As Chinese forces slowly turned back the tide of Japanese expansion, Kawashima’s money trickled away, spent on supporting her drug habit and securing protection from the military through bribes. In August 1945, Soviet forces invaded Manchukuo, capturing Puyi and putting an end to the Japanese regime. On October 10, 1945, Chinese troops recaptured Beijing.

The next day, police officers arrested Yoshiko Kawashima, alias Jin Bihui, alias Eastern Jewel.

Charged with treason, Kawashima was labeled a hanjian, or “race traitor,” in a highly publicized trial. When her judges lacked evidence, they turned to the novel written about her or the many sensational news reports printed over the years. “My whole life has been formed by false gossip about me,” Kawashima said from prison, “and I will die because of false gossip against me.”

She was right. A Chinese public, furious at years of Japanese brutality, demanded the death penalty for “the Mata Hari of the East.”

On March 25, 1948, Yoshiko Kawashima was led to a frost-covered prison courtyard, and shot once in the back of the head.

Wikimedia CommonsThe highly-publicized photo of Yoshiko Kawashima’s body following her execution in 1948.

But her reputation for survival, charm, and ingenuity lingered after death, and rumors of a secret escape persisted for years. Despite the publication of an infamous photo showing her body, it was claimed that, even as late as 1978, she could be seen climbing trees in Changchun, once the capital of the puppet state she helped to make a reality.

Now that you’ve learned the sad story of Yoshiko Kawashima, find out more about John Rabe and Alexander von Falkenhausen, the Nazi expatriates who fought to protect the lives of innocent Chinese civilians from the Rape of Nanjing. Then, check out these 21 harrowing photos from the Chinese civil war.