Zheng He's fleet of 317, 400-foot-long ships went from Southeast Asia to Indonesia and Africa and back again nearly a century before Europeans connected the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

China Photos/Getty ImagesPreparation for a 600th anniversary exhibition on Zheng He’s voyages in Shanghai. July 2005.

If you had been living near the coast of the island once called Ceylon in the beginning of the 15th century, you might have witnessed the slow unfolding of a waking dream.

The island, near the southern tip of India and along a busy trade route, saw plenty of ships, but never this many at the same time, and never this big; the largest of the vessels had nine towering masts. It would have appeared as though an entire navy was on its way to attack your country.

But this was not an invasion. These floating islands were the China’s treasure ships. They were there to share their empire’s bounty, collect new riches, and to inspire awe.

The man who commanded the largest fleet the world had ever seen was born far from the sea, near Kunming in southwestern China.

In early life, he was called Ma He, Ma being short for Muhammad, for he was a Chinese Muslim. His father and grandfather both bore the title of Hajj, designating one who has made the pilgrimage to Mecca.

Knowledge of Muslim culture and, possibly would prove invaluable in Ma’s later life. But Yunnan was still under Mongol control in his early childhood, and the emperor of the new Ming Dynasty was ready to oust the remnant from the holdout region.

Ma He would become Zheng He, a legendary seaman, navigator, and beloved emissary of 15th-century China.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Yongle Emperor, Zheng He’s patron.

Captured By The Ming

Ma He’s father may or may not have been loyal to the Yuan Dynasty, but he was caught in the fighting, and died at the hands of the Ming army.

The policy was to take the male children from such families into captivity. Ma He’s brother was released, but a general recognized Ma He as brave and intelligent, and so he was selected to serve the empire.

But in China, court administrators had to be eunuchs, and so at age 10 Ma He underwent full castration. The mortality rate for the horribly painful surgery was 20 percent.

But Ma He did not bleed out or succumb to infection, and he was assigned to serve Zhu Di, the fourth son of the dynasty’s founder. Zhu Di was stationed close to the northern frontier at Beiping, or Beijing.

The prince’s new attendant, who received an excellent education at Beiping, proved himself as a fighter in battles with the Mongols, and the two developed a friendship. As an honor, Zhu Di bestowed upon his trusted servant the name Zheng.

The newly minted Zheng He would also fight beside Zhu Di in his most important war, a coup to depose his nephew. They succeeded, and Zhu Di became the emperor known to history as Yongle, “eternal happiness.”

The Yongle Emperor would spend his entire reign working to prove his legitimacy. His father had declared a policy against foreign trade, but the new emperor ignored this injunction. In 1403, he set about on a campaign to win foreign support for his rule.

Zheng He would be central to the effort.

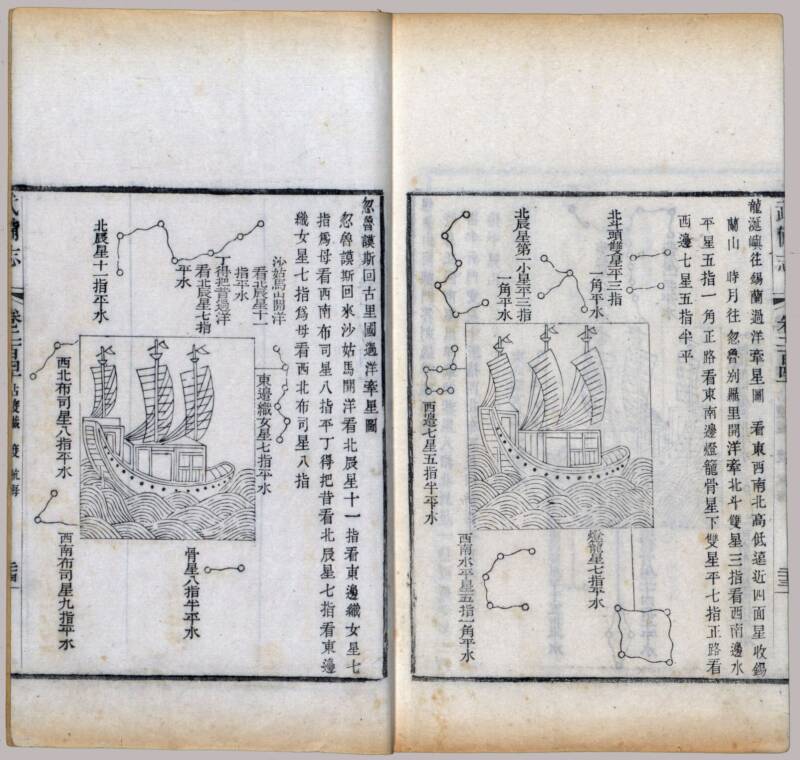

Library of CongressShips similar to the fleet of Zheng He, from a 17th-century map of his journeys. Stars used for navigation surround the main images. From the book Wu Bei Zhi, by Yuanyi Mao.

The World’s Greatest Fleet

Shipbuilders set to the task of building the outsized versions of standard junk ships. More came to work at a dry dock in the capital city of Nanjing.

Timber came in from the forests. Manufacturing of porcelain and silks, among other trade goods, was stepped up to supply the enormous fleet with as much as it could carry. Luxury goods would be presents for foreign heads of state, the rest would be exchanged for local wares.

The largest of the ships carried the treasure, while smaller boats were allocated for herds of horses, troop transport, and food. Entire vessels were filled with fresh drinking water.

Historians debate exactly how big the ships were. Some claim the official statistics, with the largest ships stretching well over 400 feet, just wouldn’t hold up on the high seas. But even if they were a more modest 300 feet, they were still bigger than anything that came before. Still, archaeological evidence has indicated the ships were as long as 500 feet — the length of three Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Had they met, the ships would have towered over of the Spanish and Portuguese ships of the following century, boasting a crew of 27,000 on 317 vessels. The flotilla that set out from Nanjing in late 1405 — 90 years before the Europeans first opened a trade route between the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean — would remain history’s largest fleet until World War I.

The First Voyage

Zheng He remained a Muslim, but he was broad-minded in religious practice. At the last Chinese port the fleet visited before departing, he paid tribute to Buddha and Tianfei, the patron goddess of sailors. And whether through her graces or not, the voyage was a success.

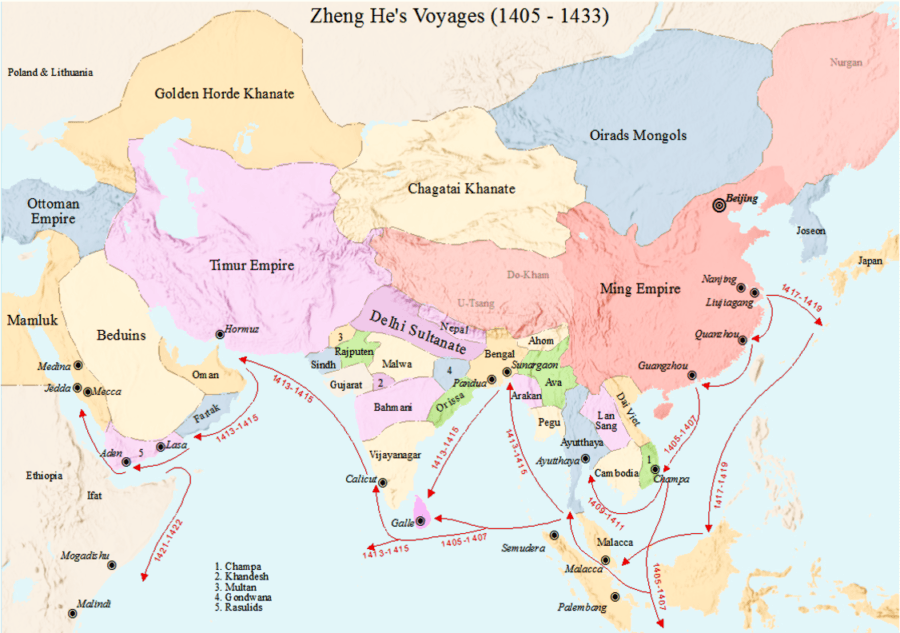

The first overseas stop was in the country then called Champa, in what’s now central Vietnam, for trade in wood and ivory. From there, the mission sailed to Siam (modern-day Thailand) and then to Java, where they met a diverse population, including Chinese migrants.

They then stopped at several ports on the island of Sumatra, including the city of Palembang, where Zheng He defeated Chinese pirate Chen Zuyi.

At Ceylon — the old name for Sri Lanka — things didn’t go so well. Zheng He was perceived as showing insufficient respect to the kingdom’s shrines. He decided their mission was best served by leaving.

Wikimedia CommonsThe continent-hopping voyages of Chinese explorer and diplomat Zheng He.

The journey’s ultimate destination was the city of Calicut, India. This entrepôt offered the greatest opportunity materially, and the fleet remained there to trade for some time, bringing loads of spices back to China.

Building on Success

The admiral himself was absent for most of the second voyage, which began almost immediately upon the fleet’s return in 1407.

Zheng He felt it important to return to China and give proper thanks to Tianfei, who had watched over them on their wildly successful first trip. He oversaw the construction of a temple in her honor on China’s southern coast.

Later trips built on the itinerary of the first, adding a second stop in India; the Arab-Persian city of Hormuz; the ancient trading center of Aden in southern Arabia; and eventually the African ports of Mogadishu, Malindi, and Zanzibar.

As in several other ports, ambassadors to China joined Zheng He in Africa, but the reception by the African leaders was much warier than that of their Asian counterparts. As with Sri Lanka, there was a concern that the Chinese fleet was there on a mission of conquest.

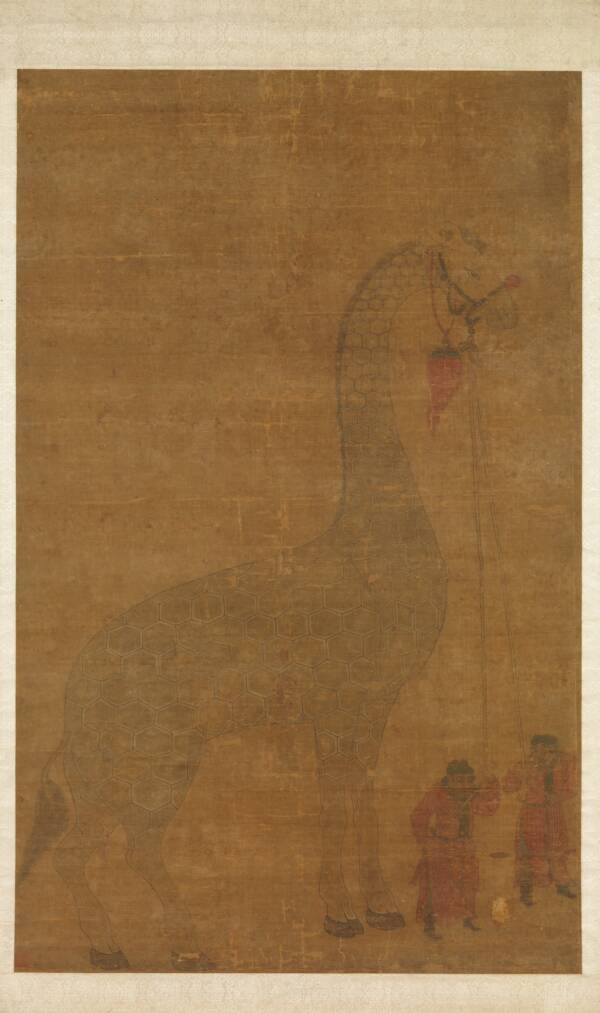

Metropolitan Museum of ArtQing Dynasty (1644-1911) copy from a 14th century painting by Shen Du, showing a giraffe from the Zheng He’s treasure ship voyages.

On one trip, a contingent split off for the Indian kingdom of Bengal. There, one of Zheng He’s captains received a giraffe.

The Chinese recipients, who had never seen giraffes before, identified the creature as the mythical qilin, a peaceful, unicorn-like beast that only showed itself in times of great peace and harmony.

The emperor was delighted. More giraffes would follow, as well as zebras, peacocks, and rhinoceroses.

Among the tribute, the Yongle Emperor especially esteemed a single, handheld reading lens. The emperor was extremely nearsighted, and the glass was a godsend.

China’s Age of Exploration Ends

Zheng He’s patron predeceased him by a decade, and the successors to the Yongle Emperor would never again show the enthusiasm for such enormous voyages.

Zheng He took on domestic projects, including the building of a giant ceramic pagoda, considered one of the wonders of its time. Late in life, Zheng He was honored with the name Sanbao Taijian, combining his nickname (Sanbao, meaning “Three Treasures”) with the word for “Grand Director.”

Zheng He would take one last journey, his seventh, in 1431. The fleet took the usual itinerary through the Arabian Peninsula. But in 1433, on the way home, Zheng He died and was buried at sea.

For some years, tributes poured in from China’s allies, but the ties eventually weakened. The most pressing matter for the Ming was a persistent threat from the Mongols.

Confucian leaders held that not only were the voyages a fiscal drain, they were misguided. Oceangoing vessels were dismantled. Foreign trade fell to pirates. And, except for descendants of Zheng He’s family, his memory fell into obscurity in his homeland.

Arterra/Universal Images Group/Getty Images Statue of Zheng He at a Chinese Taoist Temple in Java, Indonesia. 2016.

Not so among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, however. Zheng He’s memory endured among Chinese communities in what are now Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and elsewhere. Temples went up in his honor, and people recounted stories of the visits from the Chinese admiral.

History Recovered

Zheng He himself provided for his legacy by erecting monuments, both in China and abroad.

One stone tablet erected in Sri Lanka 1409, called the Galle Trilingual Inscription, bears inscriptions in Chinese, Tamil, and Persian, with messages of religious thanksgiving in all three languages. But in Chinese, the respect is paid to Buddha; the Tamil inscription honor Shiva; and the Persian text praises Allah.

China Photos/Getty ImagesReplica of a ship from Zheng He’s fleet in Nanjing. 2006.

In the run-up to the 600th anniversary of his voyages, China made up for its long-muted honoring of Zheng He. The outward-looking, forward-thinking missions offered a historic parallel to the modern country’s tremendous push into the global economy, and in particular its investment in Africa.

According to oral tradition, some people on Kenya’s Lamu Island claim Chinese sailors as their distant ancestors, and they point to some of their physical features as evidence of Asian bloodlines.

At least one DNA test corroborates the belief. If correct, the people of Lamu Island represent living symbols of the incredible reach and influence of China’s greatest ocean explorer.

After reading about the Chinese explorer Zheng He, check out China’s spellbinding stone forest. Then, these 33 China facts will blow your mind.