Given the time and place from which they hailed, it’s not too surprising that many of the best blues musicians were blind. As it happens, blindness was just the beginning of their problems.

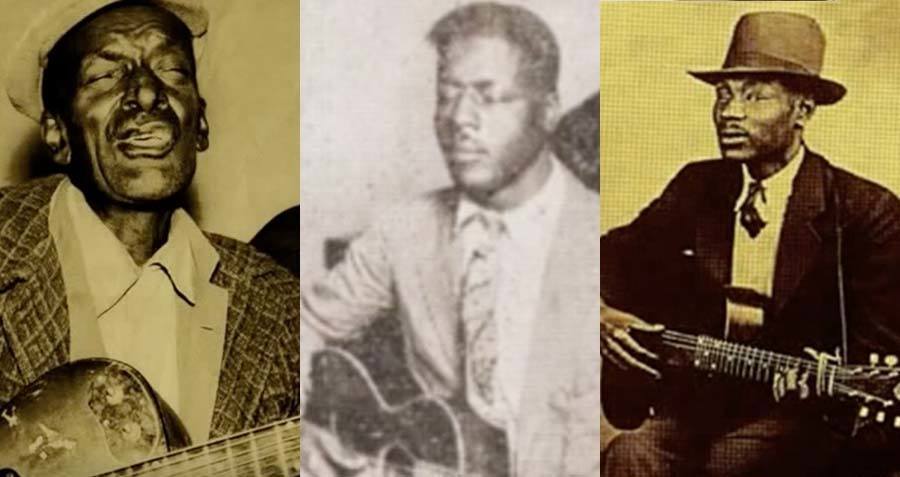

YouTube/ATI Composite

Racism, hunger, oppression, random bouts of syphilis — the life of a typical 1920s blues guitarist was not exactly a barrel of laughs. So just imagine how much worse it was being blind. Back then, a great many of them were: Blind Willie Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Lemon Jefferson…in fact, just scroll down the Blues Hall of Fame list and every third musician seems to be preceded with the word “blind.”

In the jazz and soul worlds, there wasn’t anywhere near as many blind musicians. So why the disproportionate amount of unsighted bluesmen?

“Well, there were far more blind people back at the turn of the century when these blues artists were born,” says Brett Bonner, editor of Living Blues magazine. “Several diseases that were common — and often incurable — back then caused blindness: meningitis, measles, scarlet fever, smallpox, high blood pressure, venereal disease. If the diseases were treatable, many rural poor simply couldn’t afford the doctor.”

Beyond disease, hard labor could be a common cause of blindness, too. With rural America so agrarian, the chances of accident were significantly high, and thus workers would sometimes meet with an unpleasant optical fate.

Outside of the farmland, distilling spirits could also lead to blindness. If not performed correctly, the process could result in the production of methanol, rather than ethanol; and consumed in large qualities, it could shred the optic nerves.

Given how commonplace blindness was then, perhaps a better question to ask is — why did so many of these blind people become bluesmen?

“When you were a blind child in a poor family in the rural south,” says Bonner, “you were a burden to the family because you couldn’t work on the farm like everyone else. Playing music was something a blind child could learn to do and could, as he aged, perhaps make a living doing it. Since they had to earn their keep and there were so few other possibilities available, they simply became a bluesmen out of necessity.”

Some of the bluesmen which Bonner cites were the lucky ones, who despite their affliction, were able to forge successful recording careers. Blind Lemon Jefferson, for example, became the blues darling of Paramount Records; Blind John Davis gained a big European following after touring with Big Bill Bronzy, and Sonny Terry, a blind blues-cum-country singer, went on to star in Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple.

But for the great many, day-to-day existence was tough, jostling to earn a nickel on filthy street corners, heckled and abused by a hostile, sectarian society and fighting a raging battle against disease and addiction. Every blind bluesman certainly had a tale to tell. To acquaint yourself with the most troublesome and intriguing, look no further than these five cases.