"The most sublime letter ever penned by the hand of man" wasn't written by the person you think.

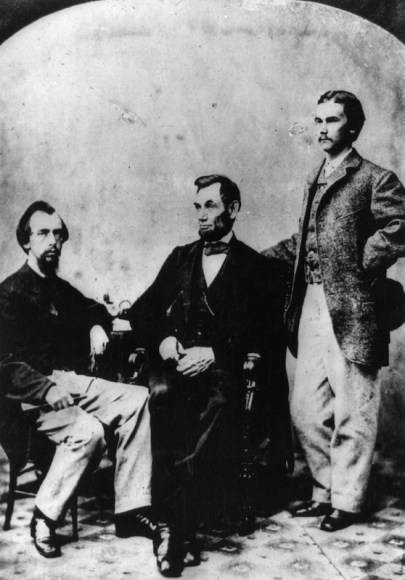

Photo12/UIG via Getty ImagesPresident Arbraham Lincoln with Secretaries John Hay and John Nicolay. Alexander Gardner, 1863.

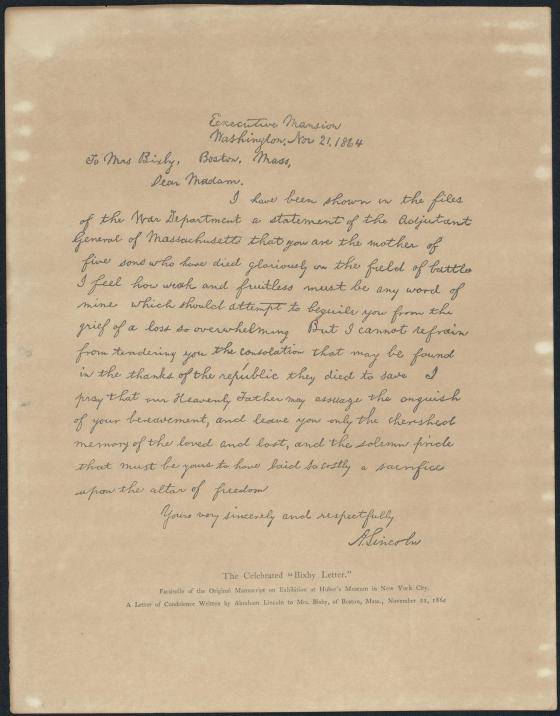

In 1864, Lydia Bixby received a letter signed by President Abraham Lincoln, a copy of which was also published in the Boston Evening Telgraph.

The words were meant to comfort Bixby, who had supposedly lost five sons in the Civil War. They went down in history as one of the great masterpieces of American writing, with journalist Henry Watterson calling the piece “the most sublime letter ever penned by the hand of man.” The letter even made an appearance in 1998’s Saving Private Ryan.

Soon after it was published, though, controversy began to swirl: did Lincoln really write the letter? Did Bixby really lose her sons?

Now, more than 150 years later, linguists think they finally have the full story.

Bixby’s sad story reached the White House after a Massachusetts general viewed documents that seemingly indicated that the widow had lost five sons who served in the Union Army. The general lauded Bixby as “the best specimen of a true-hearted Union woman I have yet seen.”

He shared her story with Governor John Andrew, who then shared the case with Washington officials.

On November 21, 1864, a letter arrived at Bixby’s Boston address.

The text, which is oddly short for such a large reputation, reads as follows:

Executive Mansion,

Washington, 21st November, 1864.Dear Madam,

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering to you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of Freedom.

Yours, very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln.

Most Union mothers would have been thrilled. Mrs. Bixby, apparently, was not.

“Mrs. Bixby, an ardent Southern sympathizer, originally from Richmond, Virginia, destroyed (the letter) shortly after receipt without realizing its value,” her great-grandson later recounted.

And according to her granddaughter, the widow “was secretly in sympathy with the Southern cause…and had ‘little good to say of President Lincoln.”

Bixby had also only lost two sons in the war. The other three had deserted to the enemy or been honorably discharged.

Regardless of the context, though, scholars maintained that the letter was one of “Lincoln’s three greatest writings” — the others being the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural Address — “upon which assessment of his literary achievement must ultimately be based.”

Unless, that is, Lincoln didn’t write it.

The rumor that Lincoln hadn’t written the Bixby letter was apparently started by the man who claimed to be the true author: Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay.

In 1904 — nearly four decades after Lincoln’s assassination — British politician John Morley had been visiting President Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt was a big fan of the Bixby letter and Morley noticed it hanging in the guest room where he was staying.

By this point in time (10 presidents later!) Hay had risen to the role of Secretary of State.

When the two men met over the course of the trip, Morley mentioned the letter.

“Morley expressed to Hay his great admiration for the Bixby letter, to which Hay listened with a quizzical look upon his face,” Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler wrote in his 1939 autobiography. “After a brief silence, John Hay told Morley that he had himself written the Bixby letter…Hay asked Morley to treat this information as strictly confidential until after his [Hay’s] death.”

“Morley did so, and told me that he had never repeated it to any one until he told it to me during a quiet talk in London at the Athenaeum on July 9, 1912,” Butler went on. “He then asked me, in my turn, to preserve the confidence of his until he, Morley, should be no longer living.”

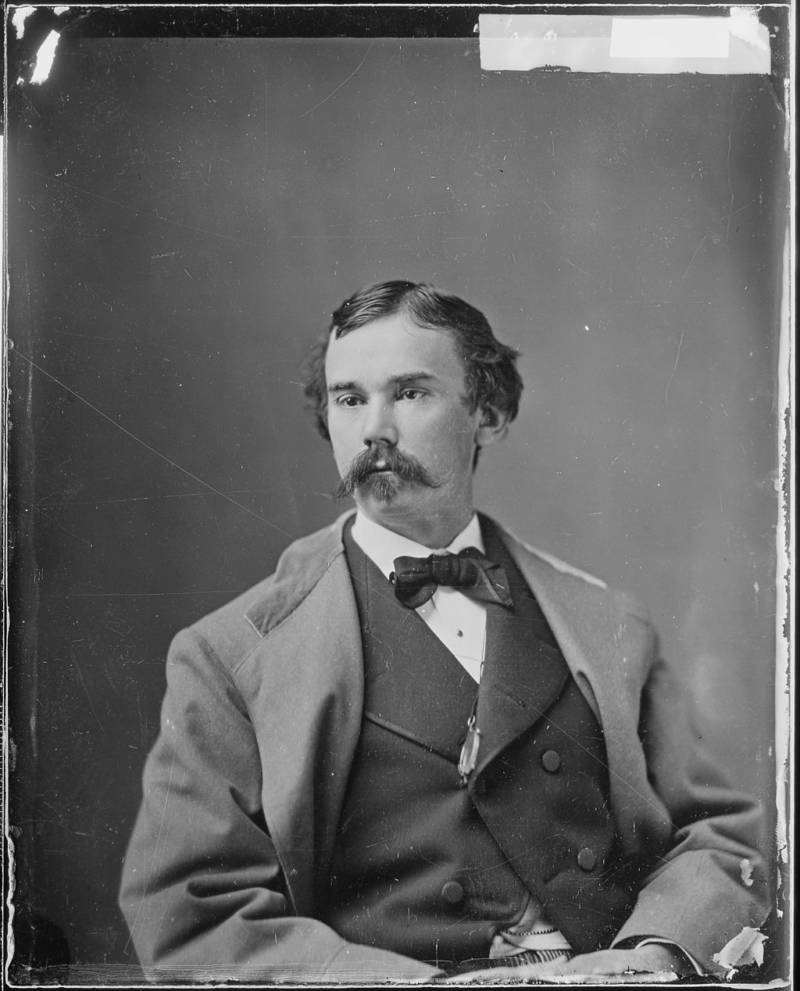

Wikimedia CommonsA young John Hay

While many have met this revelation with skepticism, several bits of evidence support it.

For one, Hay was known for frequently using the word “beguile,” which appears in the letter. It was also well-known that Lincoln wrote very few letters, and that Hay had said that he himself authored most letters the 16th president sent.

Further, Hay kept copies of the Bixby letter in scrapbooks full of his own writings and had reportedly told several other people that he was the text’s true author.

Despite this evidence, most specialists stuck by Lincoln — calling the rumor a “matter of British tea-table gossip.”

It’s fishy, they reasoned, that the story had never circulated until all the main characters died.

Plus, the letter was only 139 words. It would be impossible to conclusively deduce its author off such a small sample.

That’s where they were wrong, though.

In a paper that will be presented next week, a team of forensic linguists argues they’ve officially found the letter’s true author.

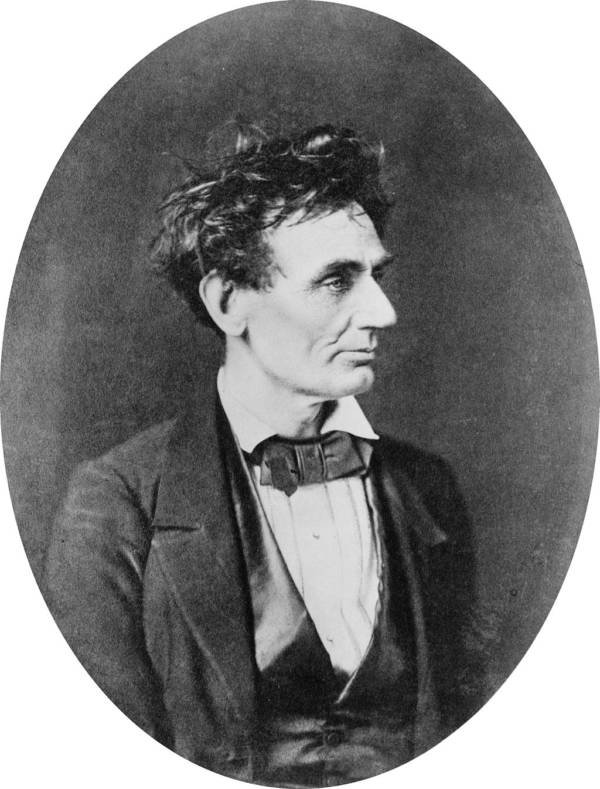

Library of CongressLincoln in 1857, seven years before the Bixby letter was written.

The Bixby letter, the numbers apparently show, was written by John Hay.

“We’d never heard of Hay but we’d heard of Lincoln, obviously, and there’s loads of data,” Jack Grieve, one of the researchers who published the study in the Digital Scholarship in the Humanities journal, told Time.

They reasoned that speech patterns can be analyzed at a smaller level than words. It’s a method they developed themselves called n-gram tracing.

An n-gram is a “sequence of one or more linguistic forms.”

Every sentence is made up of various word sequences and every word is made up of letter sequences. All of these individual patterns can be broken down.

When imported large samples of both Lincoln and Hay’s other documents into a computer model focused on finding n-grams, the results were conclusive: the tracing method identified Hay as the Bixby letter’s author 90 percent of the time.

The other 10 percent of the time, the results came back inconclusive.

This might be a bummer for some Lincoln fans. But, we’ll always have Gettysburg.

Either way, it may be best to think of this discovery the same way one prescient journalist did all the way back in 1925:

“If under the merciless hand of investigation it should be shown that this remarkable document was not only based upon misinformation but was not the composition of Lincoln himself, the letter to Mrs. Bixby would still remain…One of the finest specimens of pure English extant.”

Next, check out these 33 fascinating facts you never knew about Abraham Lincoln and see why some people suspect that Honest Abe was gay. Then, see some letters written by a Civil War soldier that reveal what the conflict was really like for those fighting it on the ground.