When an aristocratic Englishman came to New York to perform Shakespeare's Macbeth in 1849, anti-English and anti-elite rioters clashed with militia, leaving 22 dead.

In 1849, one of the deadliest riots in American history left 22 dead and more than 120 injured in what became known as the Astor Place Riot. The cause was ostensibly a fan rivalry over their favorite Shakespearean actors, but there were deeper elements at play.

A Time Of Upheaval

Mid-19th-century New York City — also known as the antebellum period — was in the throes of accelerated change. The city had swelled in importance with the opening of the Erie Canal, in 1821 which linked it with the vast interiors of North America. From a population of just over 60,000 in 1800, by 1850 there were 515,000 people inhabiting the city.

Many of these were newly come Irish immigrants who, starting in 1845, fled their country in droves to escape the Irish Potato Famine. By 1850, a quarter of New York’s population was Irish.

Wikimedia CommonsA bird’s eye view of New York City in 1873. When the Astor Place Riot happened in 1849, the Brooklyn Bridge (right) hadn’t even begun construction.

Many Irish blamed (with some justification), the British government and its policies for the Great Famine, leading to resentment of those immigrants against the English. At the same time, boundary disputes and economic tensions between Britain and the United States led to a streak of Anglophobic sentiment in America at large.

This was coupled with a developing nativist streak among the white, native-born working class who viewed the English as aristocratic and anti-American. As a result, the English as a group were resented by large swaths of the population.

Dramatis Personae

Into this maelstrom of class tension and xenophobic sentiment stepped the English actor William Charles Macready. Born in London in 1793, Macready had become a very famous Shakespeare actor by 1849. At that time, Shakespeare performances cut across all class lines and were popular entertainment.

Macready was known for giving subdued, genteel, and refined performances in an attempt to elevate the art of theatre, to make it more in line with high culture.

He agreed to stage a series of performances at the recently opened Astor Opera House, whose owners wished to cater to the upper classes of New York society. Little did Macready know that he would become the focus of class and nationalistic rage.

Wikimedia Commons>English thespian William Charles Macready had successfully toured the United States in the 1840s, prior to the Astor Place Riot.

Macready’s rival was the American Shakespearean actor Edwin Forrest. Thirteen years younger than Macready, Forrest gave forceful, histrionic, and masculine performances that catered more to the lower classes, with which he was wildly popular.

Forrest had visited England, watched Macready perform, and hissed at him. Macready had said that Forrest lacked taste.

The rivalry escalated, in part due to overzealous reporters hungry for a sexy story. Probably to irritate his rival, Forrest starred in Shakespearean productions during Macready’s American tour.

Act One: Performance, Interrupted

On May 7, 1849 Macready opened Macbeth at the Astor Place Opera House, while Forrest performed the exact same play at the more downscale but much larger Broadway Theater just a few blocks away.

Macready found that a good portion of the audience were Forrest fans who had come to hiss and heckle him.

According to historian J.T. Headley, “Macready had hardly uttered a single sentence before his voice was totally drowned in the uproar… He then attempted to go on and out bellow, if possible, the audience. But it was like shouting amid the roar of breakers.”

Wikimedia CommonsA Philadelphia native, Edwin Forrest had a macho style that American audiences adored.

Some Macready supporters in attendance shouted, “Shame, shame!” But the crowd shouted back. “Go off the stage, you English fool!” they yelled. “Hoo! Three cheers for Ned Forrest!… Down with the codfish aristocracy!”

Hecklers threw apples, potatoes, lemons, and small change were thrown at Macready — and a couple of them even threw chairs at his head, which luckily missed.

Once Macready seriously feared for his safety, he left the stage threw a back door and was whisked away by a stagecoach. He announced that he would return to England, cancelling the rest of his stateside performances.

Act Two: The Show Must Go On

Forty-six of the city’s elite, including writers Washington Irving and Herman Melville, sent an appeal to Macready admonishing the incident, and urged him to go on with the show.

Part of the note assured the English actor “that the good sense and respect for order prevailing in this community will sustain you on the subsequent nights of your performance.”

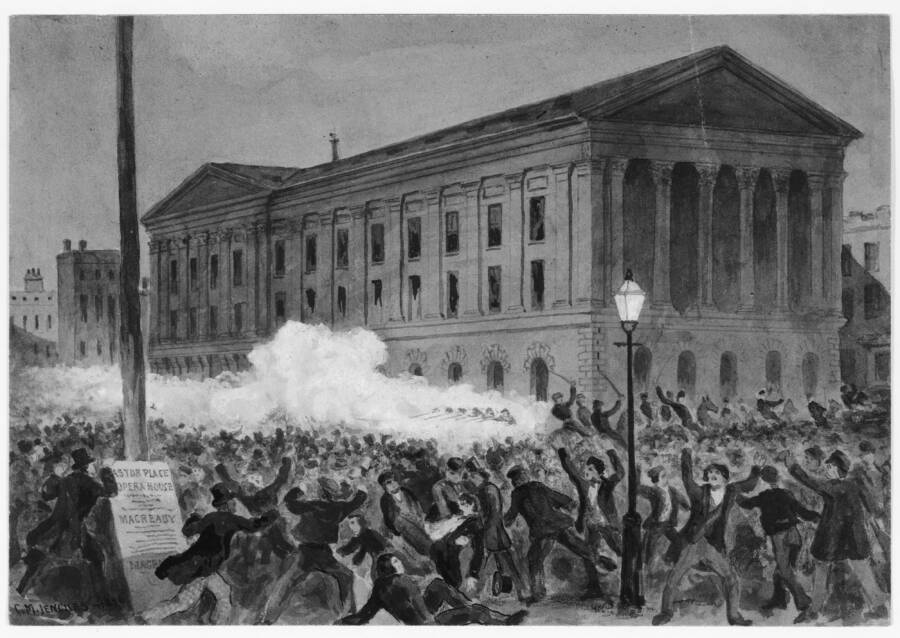

Wikimedia CommonsThe Astor Opera House, also known as the Astor Place Opera House, was demolished about 50 years after the Astor Place Riot of 1849.

Macready agreed that the show would go on; he would appear at the Astor Place Opera House on the 10th of May.

Act Three: Who Shall Rule the City?

After Macready’s performance was announced, anti-Macready forces sped to action.

Isaiah Rynders, a political operator and gang leader, was a fervent supporter of Forrest and the main agitator of the anti-Macready crowd. It was he who obtained 500 tickets for Macready’s first performance and handed them out to his “b’hoys”, which resulted in the disruption.

Rynders had also approached Forrest, asking him whether he approved of the anti-Macready uprising. “Two wrongs do not make a right,” he said. But he also added, “let the people do as they please.”

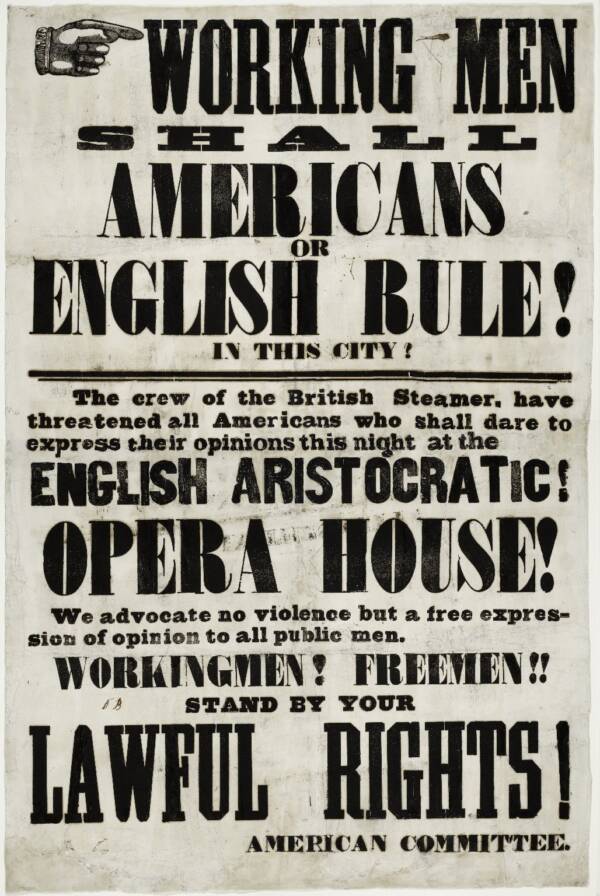

Wikimedia CommonsPosters like this one helped instigate the Astor Place Riot.

Rynders was also an ally and operative for the Irish-affiliated Democratic political machine, Tammany Hall, and saw an opportunity to embarrass the newly elected Whig Mayor, Caleb S. Woodhull.

Theaters were more than performance in the early 19th century. They were seen as public platforms where citizens could air their grievances.

Rynders arranged to have incendiary posters posted throughout the city reading in part: “WORKING MEN, SHALL AMERICANS OR ENGLISH RULE IN THIS CITY?” It urged citizens to go to the “English Aristocratic Opera House” to exercise their “free expression.”

Act Four: The Gathering Storm

As word spread of the potential riot at the Astor Place Opera House, 300 police mobilized under Chief George Matsell. But the chief informed the mayor that his force was insufficient to suppress mob violence.

Mayor Woodhull feared a riot — so early in his tenure — and so he brought in reinforcements. He contacted Major-General Charles Sandford, the head of New York’s Seventh Regiment of the state militia, who mobilized two divisions to Washington Square Park.

When the evening of the performance arrived, police were stationed inside and outside the Opera House. Meanwhile, a very large crowd of 10,000 assembled outside, a mix of both native-born Americans and Irish immigrants. Both groups had common cause in anti-English and anti-aristocratic sentiment.

The police made sure that only ticket-holders were allowed inside, and the theatre had already worked to sort out legitimate patrons from potential rioters. They locked the doors and even barricaded the windows to keep people from charging inside — but forgot one window.

And the rioters came with stones.

Act Four: The Astor Place Riot

Macready’s Macbeth started promptly at 7:30 p.m., and a small group of anti-Macready attendees who had managed to make it past the police checkpoint immediately tried to disrupt it.

All together, they made a run for the stage to seize Macready, but the undercover policemen grabbed them and locked them inside a makeshift prison in the building. But, according to the New York Herald, the prisoners gathered some wood shavings, held them up to a gaslight, and set their cell on fire.

Meanwhile, the crowd outside threw bricks and stones through the unprotected window. When the police beat them for trying to force open the front door, rioters destroyed nearby street lamps, breaking them to pieces and putting out the lights.

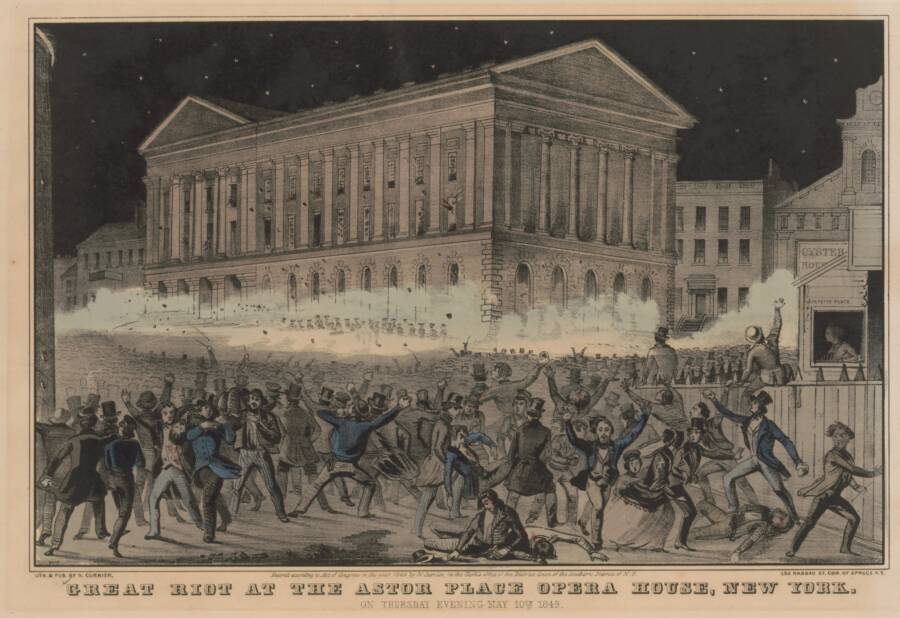

Wikimedia CommonsA scene of the Astor Place Riot.

Somehow, the show went on, although according to Headley it was “a spiritless affair.” The audience wasn’t focused on the action onstage, but rather the action in the audience and outside the theatre. “Every ear was turned to hear the muffled roar of the voices outside, which every moment increased in power as the mighty multitude kept swelling in numbers.”

The play ended early, and Macready fled the Opera House to his hotel in disguise.

Outside, the crowd massed in order to ram in to doors of the Opera House. As the Herald described, “In the front and rear the fierce assaults of the mob, as they thundered at the doors, resounded all over the theatre, whilst the shouts and yells of the assailants were terrific.”

Being out of his depth, Chief Matsell called for the militia stationed at City Hall, about a mile and a half away. A troop of horses arrived at 9:15 p.m., but the mob was hardly intimidated.

They rushed for a pile of paving stones (the city was constructing a sewer in the neighborhood) and began pelting the militia, injuring several including a commanding officer.

Cries of “Burn the damned den of aristocracy!” were heard. Warnings to disperse were not heeded. One rioter bared his chest and said, “Fire if you dare — take the life of a freeborn American for a bloody British actor!”

Act Five: The Storm Breaks

The Seventh Regiment fired.

The first volley was over the mob’s heads, so as to not let the scene devolve into bloody murder. But this only egged on the crowd — “Come on, boys!” they shouted. “They have blank cartridges and leather flints!”

Disgusted by the prospect of being pelted to death, a general ordered the men to fire, point blank. According to some sources, he ordered the troops to aim low in order to wound — not kill.

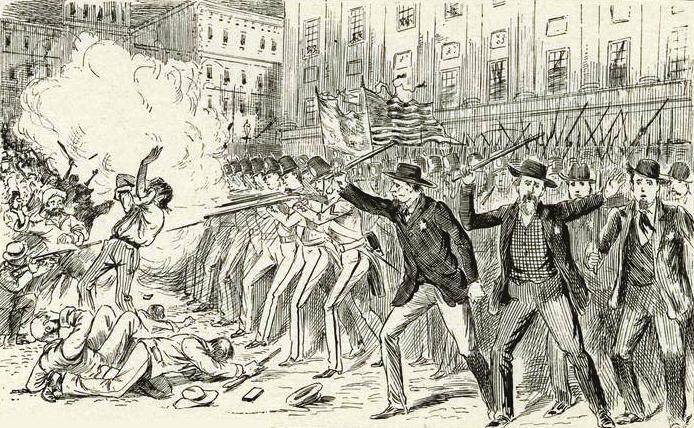

Wikimedia CommonsSoldiers met the rioters’ stones with bullets.

Even with the threat of deadly ammunition, the rioters continued to seize and throw stones, but a second volley scattered the crowd in panic.

The Seventh Regiment then lined up in front of the Opera House. It took two more volleys for the rioters to retire into the night.

By the time the militia had cleared the streets, 18 lay dead and several more would die of wounds over the next week for a total death count of at least 22. Dozens were wounded and more than 100 rioters were arrested.

At that point, it was the deadliest riot in the city’s history.

Epilogue

The next day, the city became a police state. A thousand special deputies, 2,000 infantry, cavalry, and artillery prowled the streets.

That evening a protest was held at City Hall Park condemning the government for, as Isaiah Rynders put it, ending the “lives of inoffensive citizens – to please an aristocratic Englishman backed by a few sycophantic Americans.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe site of the Astor Place Opera House is now a Starbucks.

A worked-up crowd stormed out of the park and up to Astor Place and began throwing stones at troops from behind barricades. The militia wasn’t having any of it and charged the crowd with fixed bayonets, dispersing them easily.

The Astor Place Opera House never recovered, earning the nicknames “DisAstor Place” and the “Massacre Opera House.” The venue was eventually sold and, 50 years after the riots, it was demolished and replaced with a library called Clinton Hall, which still stands today (though now it’s a Starbucks).

Ten rioters were eventually convicted, fined, and put into prison the following September. Isaiah Rynders escaped conviction with the help of attorney John Van Buren, the ex-president’s son.

The most lasting effect of the Astor Place Riot was that it highlighted the growing class divide in society between rich and poor. This was but a foretaste of the deep divisions of American society and wealth gap found in the later part of the century during the so-called Gilded Age.

After learning about the deadly Astor Place Opera House riot of 1849, take a look at some even more violent episodes in New York City’s history, including the Dead Rabbits Riot of 1857 and the infamous New York City Draft Riots of 1863.