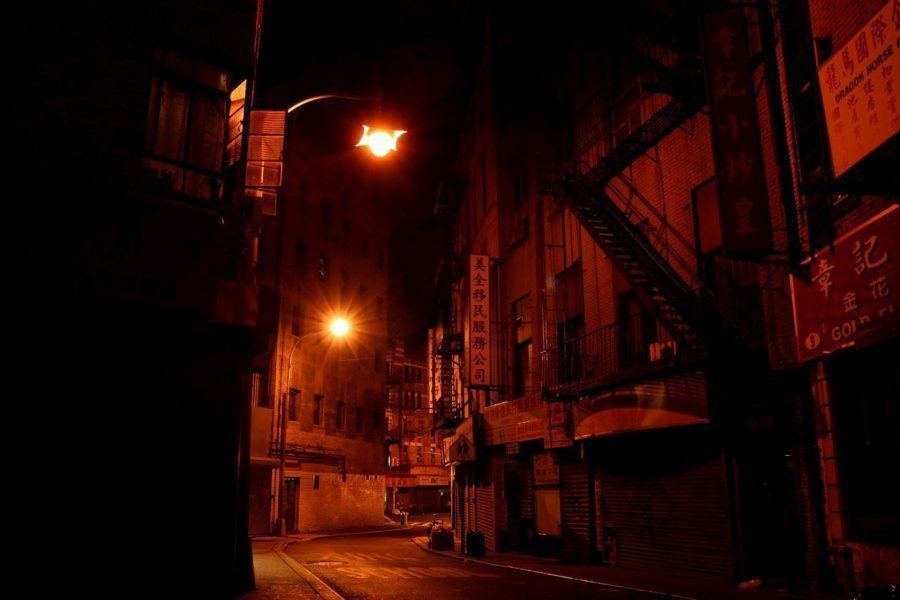

How New York City's Doyers Street became the deadliest street in American history, known forever as The Bloody Angle.

Image Source: Flickr

New York City has always been inextricably linked with its gangs. In simply reading that sentence, you’re likely already remembering images from Gangs of New York, The Godfather, The Warriors and on and on.

But what you’re probably not picturing is a strange little 200-yard stretch called Doyers Street, one of the few streets in Manhattan bent at a nearly 90-degree angle — and one of the bloodiest streets in American history.

On Doyers Street, the history of the immigrants who built America is clear, and it’s filled with violence, racism, xenophobia and segregation. This forgotten cranny, buried deep in the heart of Chinatown, has seen the most gang violence in the history of the city, and, by some estimations, the country.

Whether it was because of bullets or hatchets, Doyers Street was literally stained red during its most violent years, earning the street its immortal nickname: “The Bloody Angle.” Exactly how it became so bloody, and what’s become of it since, is quite a tale.

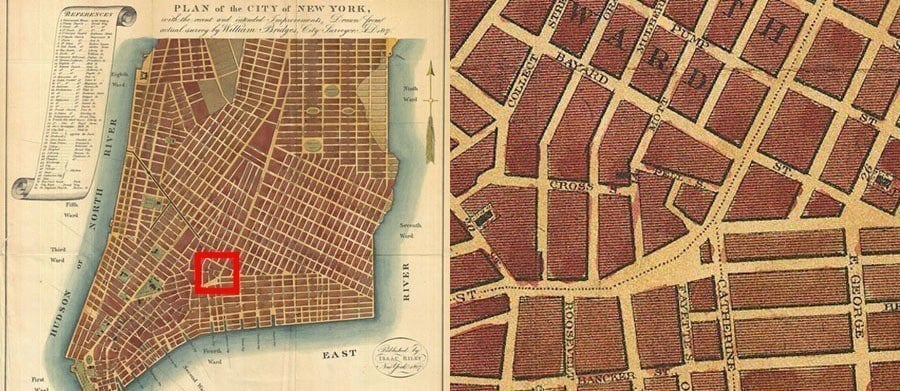

Doyers Street on an 1807 Manhattan map. Left: close up of area squared in red. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

The amorphous and growing area of lower Manhattan known today as Chinatown wasn’t always so large. Manhattan’s Lower East Side was home to Irish, Jewish, and Italian immigrants long before the Chinese, and tight immigration laws kept the Chinese population at a minimum until after World War II.

But by the 1880s, enough Chinese immigrants had put down roots such that Mott, Pell, and Bayard streets had transformed into the lean corridors of Chinatown. Doyers Street became a small, yet culturally significant, shortcut through those streets.

All along Doyers Street, tall, lanky tenement buildings were pocketed with fan-tan gambling houses and opium dens (perfectly legal at the time). Upper-floor rooms and pool hall bars were filled with prostitutes.

At the time, the Chinese population in America was a bachelor society of men who had worked the cross-country railroads and California gold mines. Chinese women never even had a chance to make it to the states, due to policymakers who had started to fear the influx of male Chinese immigrants and enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. With the resulting abnormally high male-to-female ratio, Chinatown became known as a hotbed of masculine vice.

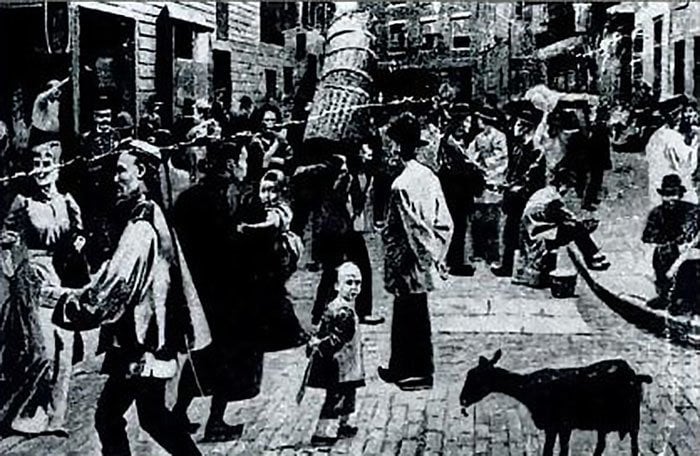

Doyers Street as depicted on a postcard in 1898.

Soon — in the larger context of white America’s pervasive racism and xenophobia — Chinatown was labeled, even in the mainstream press, as a hopeless opium-and-prostitute-ridden slum. As The New York Times wrote about Chinatown in 1880: “There are some streets in New-York that begin with a very fair outlook, but grow so much worse with every block, as you walk through them, that there is no telling what they might come to if they were long enough.”

While those words paint an ominous picture of New York City’s minority populations and the streets they inhabited, Doyers Street was, at the time, mostly peaceful. The sharp bend was an important cultural meeting point for Chinatown residents, and the local Tong (gang) members even declared the street’s Chinese Theater safe and neutral ground.

But on the night of August 7, 1905, that all changed — and Doyers Street started to become The Bloody Angle.

For those in charge, the act passed to keep more Chinese people from emigrating to the United States wasn’t enough. Fear of the Chinese population taking white middle class jobs caused those who had made it to the USA to be relegated to laundries and restaurants. For men not interested in either of those professions, there weren’t many other options besides gang life.

In the early 1900s, two major factions were battling for control of vice in Chinatown: the Hip Sing Tong (along with their allies the Four Brothers) and the On Leong Tong. These gangs ran everything from the opium dens to the entertainment centers to the prostitution rings, largely without threat from law enforcement, allowing the gangs to leave unchecked violence in their wake.

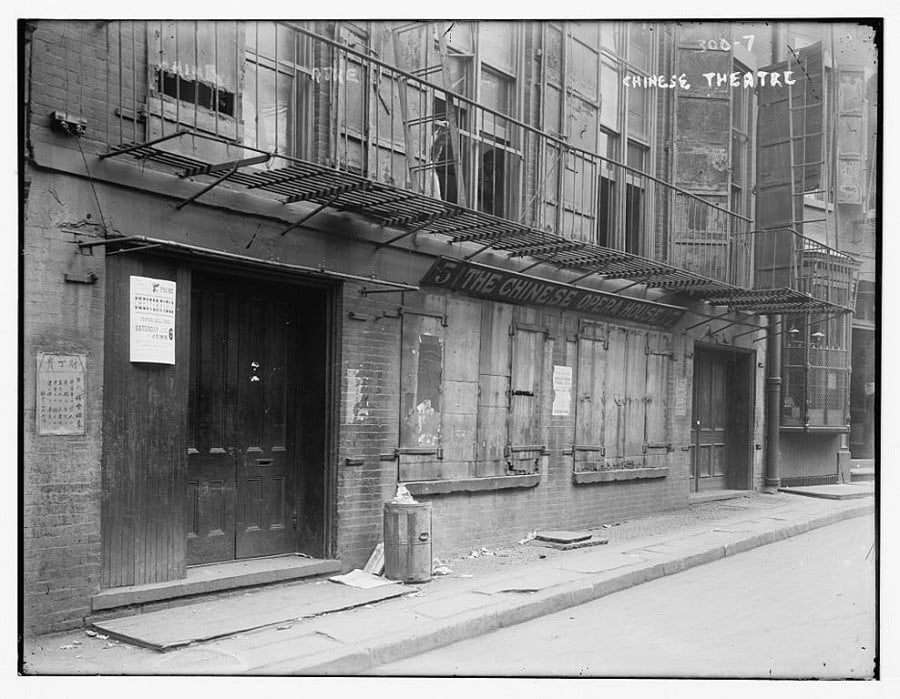

But inside Doyers Street’s Chinese Theater, there was usually peace, as members of the rival gangs sat calmly on opposite sides of the theater and avoided conversation as adamantly as Republicans and Democrats listening to a State of the Union address.

On the night of August 7, 1905, members of both gangs packed into the Chinese Theater to watch a play entitled The King’s Daughter. As one New York newspaper, The Sun, estimated, “There were probably 500 Chinamen in the house and they came from most of the laundries in Manhattan, The Bronx and Jersey City.”

The Chinese Theater, sometime between 1893 and 1911.

Suddenly, a Hip Sing gangster lit a string of firecrackers and threw them onto the stage. This drew the attention of the unsuspecting audience, and allowed 10 other Hip Sing members who were in on the plan to pull pistols out of their pockets and sleeves, and spray bullets toward four off-guard On Leong Tong members.

“Four men went down at the first volley and lay on the floor of the theater, trampled on by the yellow men that were doing their best to get out of the house,” The Sun‘s account reads. “The assassins kept on firing, and the only wonder is that a dozen weren’t ready for the hospital when they quit.”

Sailors, marines, policemen, and rubberneckers rushed to the Chinese Theater to get a glimpse of the aftermath, witnessing crime in real life being the reality TV of the early 1900s, the “true crime” craze of recent years magnified tenfold.

The killers likely slipped away using one of the many underground tunnels that branched out from Doyers Street. No one involved in the massacre was ever charged for the crimes.

But the massacre did have one long-lasting effect: it kicked off a years-long Tong war all centered around the very spot it had begun — the bend on Doyers Street.

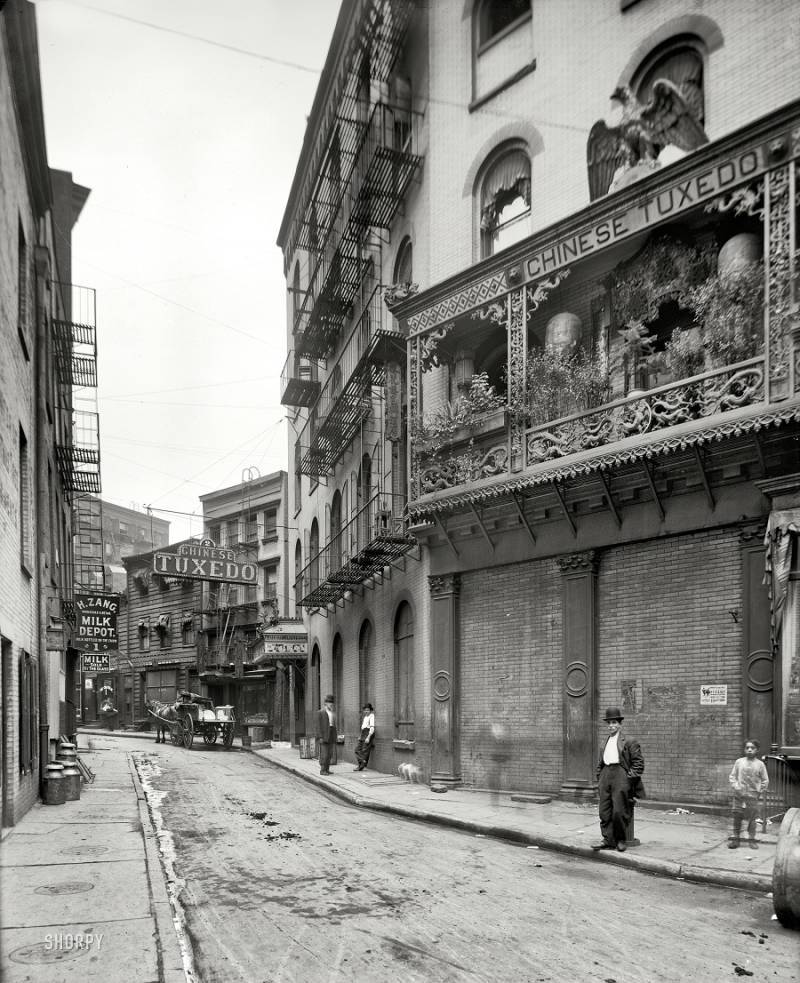

The Chinese Tuxedo restaurant at 2 Doyers Street in 1901. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

By 1909, four years after the massacre, tensions between the Hip Sings and On Leongs had escalated to an alarming level. Like so many great struggles, from the Trojan War to West Side Story, this climax of the Tong Wars began with a fight over a woman. In this case, it was the murder of a sex slave named Bow Kum.

A Four Brothers member named Low Hee Tong originally purchased Bow Kum for $3,000 in San Francisco, but when he was arrested and unable to produce a marriage license for her, Bow Kum was taken in by Christian missionaries. Eventually, an On Leong Tong member named Tchin Len married Bow Kum and took her to New York, taking with him what Low Hee Tong believed was his property and investment. Tchin Len disagreed.

Low Hee Tong gathered the Hip Sings and Four Brothers in New York to demand the On Leongs pay back what he believed he was owed. The On Leongs refused. This proved to be the final straw.

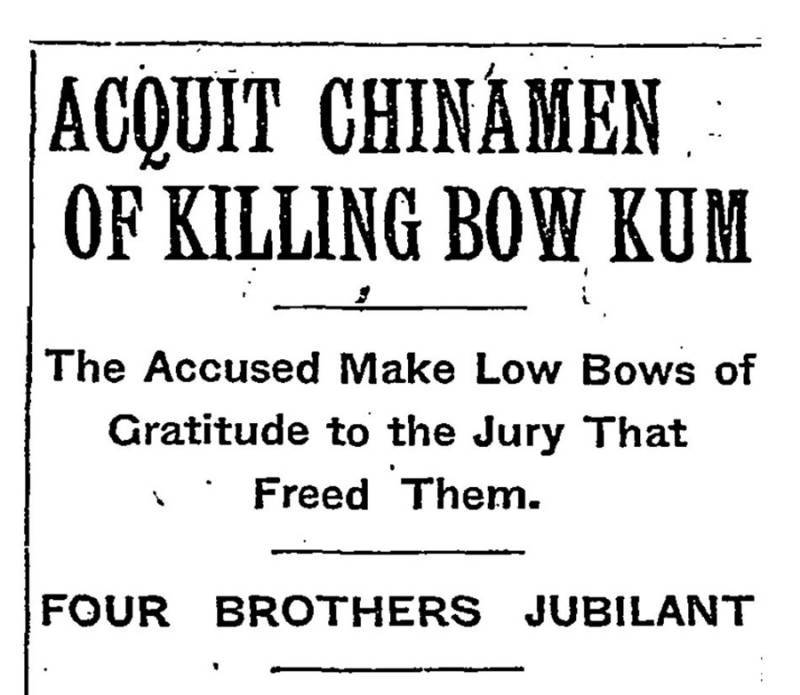

On the night of August 15, 1909, almost four years to the day after the massacre at the Chinese Theater, a Hip Sing-allied hitman snuck into Tchin Len’s home on Mott Street. He stabbed Bow Kum in the heart, slashed her body and cut off her fingers. In the ensuing trial, no one was found guilty.

The New York Times headline after Bow Kum’s alleged murderers were found not guilty. Image Source: ACQUIT CHINAMEN OF KILLING BOW KUM; The Accused Make Low Bows of Gratitude to the Jury That Freed Them.

From that point on, it was all-out war. Some 50 people soon died and Bow Kum was far from the only innocent to be caught in the crossfire.

According to one account, it was always possible to tell which gang was responsible for each murder — the On Leongs only used Smith & Wesson guns, while the Hip Sings used strictly Colts. It was another kind of weapon, however, that helped immortalize the 1909 Tong War, and The Bloody Angle in particular: the hatchet.

Gangsters carrying hatchets would wait around one side of the Bloody Angle until their victims blindly turned the corner. Then they would pounce, slash, and escape via the underground tunnels, leaving the cobblestone street soaking in the victim’s blood.

By some accounts, this is where the term “hatchet man” originated.

As a result of this violence, local Chinese businessmen were losing a lot of money — only the newspaper boys peddling the stories of war on the streets were profiting from the conflict. Even Hip Sing leader Mock Duck and the On Leong leader — and unofficial “Mayor of Chinatown” — Tom Lee were losing money — after all, it’s hard to promise extortion and draw in opium den customers when the streets can’t be crossed.

Time and again, various peace negotiations punctuated episodes of intense violence, but failed to broker a permanent peace. And when peace finally did come to the Bloody Angle in 1913, it didn’t last forever.

Bloody Angle In Modern History

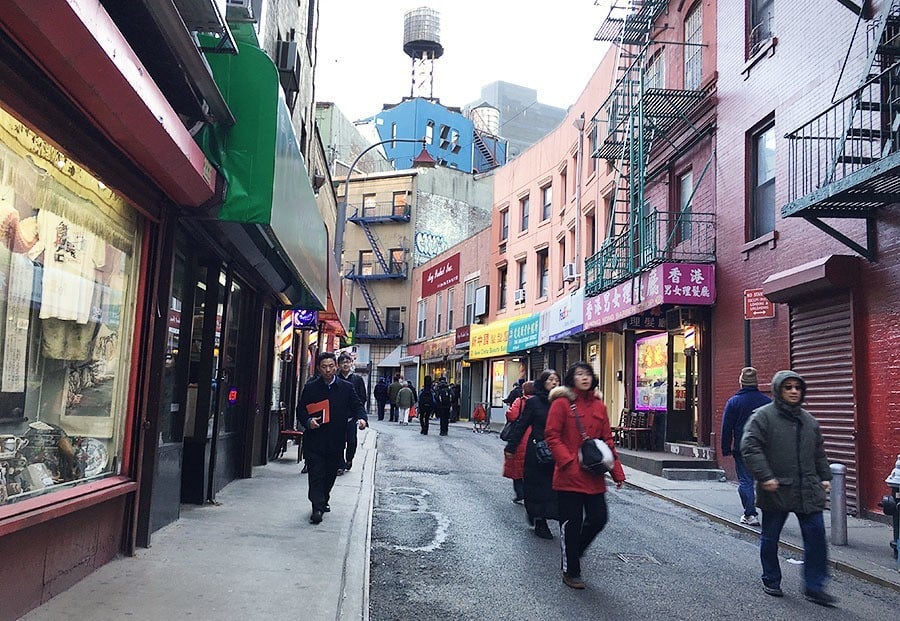

Doyers Street today. Image Source: Nickolaus Hines.

In 1989, near the end of New York City’s most violent decade, The Bloody Angle once again earned its name. This time, the fighting was between a Chinese gang called the Flying Dragons — a young gang that is largely controlled by members of the century-old Hip Sing Tong — and a Vietnamese gang called BTK (Born To Kill).

This time around, any sense of boundaries was gone. The BTKs were known for robberies, assaults, murders, and even attacks on police officers. In the summer of 1988, BTK members threw a bomb filled with .22-caliber bullets into a police car in Chinatown. The reason? The police had recently arrested several BTK members for selling counterfeit Rolex watches.

“The Vietnamese have suddenly become our biggest problem,” Nancy Ryan, chief of what was then known as Manhattan’s Oriental gang unit, told The New York Times in 1989. “Even the other Chinese gangs say they are wild and unpredictable and are afraid of them.”

The BTKs swelled their ranks with teenagers and young men from Vietnam. Most of the members had been relocated from Saigon during the Vietnam War, which is where their name came from: “Born To Kill” was allegedly often written on the helmets of U.S. airmen fighting against the Viet Cong. They were rootless, ruthless and not afraid to bring down the hierarchy of the city government or the established Chinese gangs through extortion and rival turf acquisition.

Members of the Green Dragons in 1994. The Green Dragons were an Asian-American gang that operated out of Flushing and Chinatown. Image Source: Gorilla Convict

It wasn’t until 1994 that Pell, Mott, Bayard, and Doyers streets had finally fallen quiet. Hip Sing leader and the “Godfather of Chinatown” Benny Ong’s health had declined. The illegal gambling dens had been run off by law enforcement, and rival gangs no longer had as many turf and business interests to fight over. Drunk wanderers now urinated where powerful gang members once held court.

Finally, after generations of infighting, The Bloody Angle was enjoying a kind of armistice. Its dark history, however, is never far behind.

“Law-enforcement officials say more people have died violently at Bloody Angle, the crook at Doyer Street near Pell,” Jane Lii wrote in The New York Times in 1994, “than at any other intersection in America.”

Present day Doyers Street is filled with tourists searching for an authentic Chinatown feel. Image Source: Nickolaus Hines.

The people walking on the asphalt of Doyers Street today are likely oblivious to the carnage of the past. Tour groups filled with people from middle America pass through on a schedule. Hair salons and tourist shops line both sides of the street.

The tunnels that were once crucial methods of escape have been taken over by job placement businesses for new immigrants, while Hendrick Doyer’s brewery has been turned into what is arguably the ugliest United States Post Office in the city.

Nextdoor to where the Chinese Theater once sat is a sign of ever-encroaching gentrification: a bar called Apotheke that sells premium cocktails designed by a mixologist for $16 each.

Image Source: Flickr

Yet if you look hard enough though, the true history of the street and the secrets most people will never know lie just inside the next shop and around the bend.