"Cancer Alley" is home to hundreds of chemical plants and refineries — and their industrial waste has created a health crisis for the majority-Black residents living nearby.

Jim West / Alamy Stock PhotoA Dow Chemical plant in Hahnville, Louisiana.

Along the twisting length of the Mississippi River, there’s a stretch of 85 miles known as “Cancer Alley.” There, the region’s majority-Black residents have long complained of high rates of cancer, miscarriages, and other ailments. And they say they know the cause: the hundreds of chemical plants that operate cheek-to-jowl with their homes and schools.

Though both plant operators and public officials have often pushed back against the moniker, recent studies suggest that the residents of Cancer Alley have a point. The tens of thousands of locals face an “elevated risk” of cancer, respiratory ailments, and reproductive health problems.

To longtime residents, this is hardly a surprise. Over the past several decades they’ve seen their pets lose their fur and watched as their flowers failed to grow and fruits came in deformed. Worse — much worse — they’ve watched as their loved ones died, or as women in their small towns suffered from high rates of miscarriages.

So how did Cancer Alley develop in the first place?

From Plantations To Chemical Plants

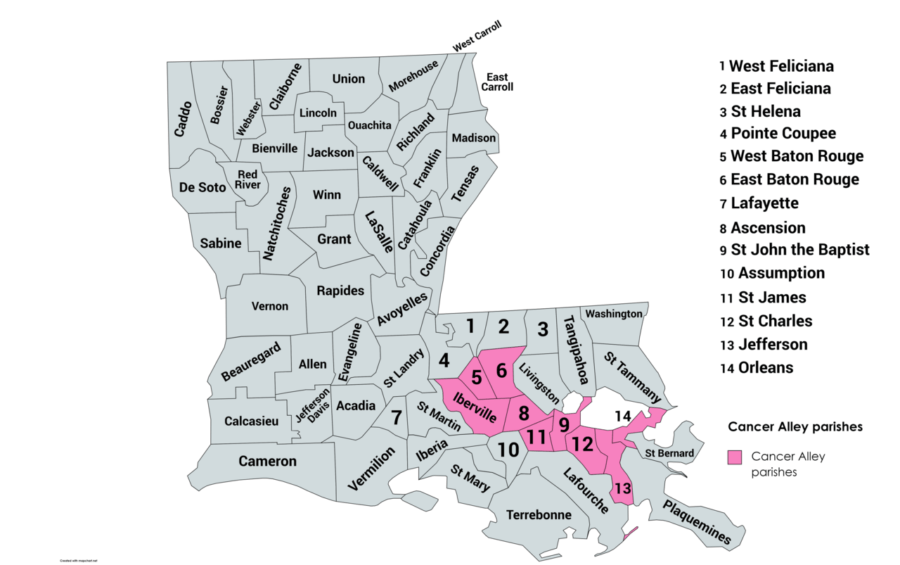

Patapsco913/Wikimedia CommonsParishes in “Cancer Alley.”

The history of Cancer Alley really begins more than two hundred years ago, when much of the land along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans was used by plantations. When slavery ended, many Black residents remained near the plantations as sharecroppers.

They watched as the countryside changed, first with the construction of oil refineries at the beginning of the 20th century and then with petrochemical plants along the Mississippi River in the 1960s.

“These giant plots of land owned by plantations were the perfect sites to build these big oil refineries and petrochemical plants near the river,” Halle Parker, co-host of WWNO and WRKF’s podcast “Sea Change,” which covered the EPA’s investigation into whether Louisiana had discriminated against Black communities in Cancer Alley, explained to NPR.

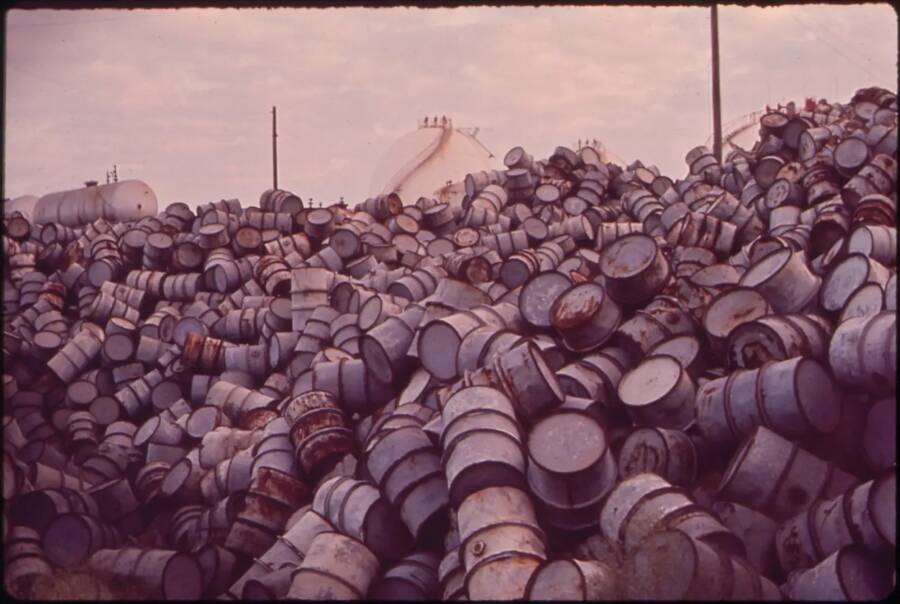

U.S. National Archives and Records AdministrationA mountain of oil drums near the Baton Rouge Exxon Mobil Refinery along the Mississippi River. December 1972.

She continued: “It came with all of these perks, perks like only having to deal with one landowner and easy access to the river for transport and export of their goods. But the land near those plantations is also where the people who used to be enslaved settled. So when the plants came to town, it also put those Black communities right up against the fence line.”

By the 1970s, dozens of refineries and chemical plants had sprung up in the region. The plants were largely unregulated in the years before the creation Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 and — despite a promise to create jobs — very rarely hired locals.

Then the locals started to get sick.

Asthma, Miscarriages, And Death: Life Inside Cancer Alley

Eli Reed for Human Rights WatchThe Louisiana skyline in Cancer Alley, smeared by smoke or steam.

As the decades passed, many living in Cancer Alley sensed that something had gone wrong. ProPublica reports that a golden mist — nighttime chemical releases — floated over the small towns near chemical plants, and that residents often found dead birds in their lawns.

Lightning bugs vanished from some places, as did dragonflies and river shrimp. Trees grew deformed fruit, and flowers struggled to bloom.

In 1988, the Los Angeles Times reported that Etta Lee Gulotta, a resident of Plaquemine, started noticing the high rates of cancer deaths around her after her husband Tiger Joe — a non-smoker — suddenly died of lung cancer.

On her street, Gulotta found seven more cases of cancer. When she expanded her search to a five block radius, she found 40 more cases.

“Everywhere you turn, you find somebody’s got cancer,” she said.

About 40 minutes away, a pharmacist named Kay Gaudet in the town of St. Gabriel (population: 2,100) also began noticing an alarmingly high rate of miscarriages. First it was her sister. Then it was more than 60 other women in the span of just a year.

Alizada Studios / Alamy Stock PhotoSmoke billows from an oil refinery in Louisiana.

Increased Awareness Sparks Little Change

Human Rights Watch reports that these occurrences did not go unnoticed on a national level. In 1987, the Washington Post became the first known publication to call the area “Cancer Alley” and reported that the “air, ground, and water along this corridor are… full of carcinogens, mutagens, and embryotoxins.”

A physician told the publication that there was a “positive correlation” between high cancer rates and pollution in the area. Thirty years later, in 2019, the EPA determined that residents in certain parts of Cancer Alley were 50 times more at risk of developing cancer caused by air pollution than the national average.

But despite alarming reports like these, nothing much changed. Few studies provided conclusive answers, and state and corporate officials have long portrayed the risks in the area as “overblown.”

In response to Gaudet’s informal survey, for example, Fred Loy of the Louisiana Chemical Association told the Los Angeles Times: “They say the chemical plants are causing the miscarriages, but they have no proof. I could say they [make love] too much, and that’s the cause of the miscarriages. But then I would have no way to prove that.”

Residents, however, have long felt that they had sufficient evidence.

Matt Roth for Earthjustice/University Network for Human RightsCancer Alley residents Mary Hampton and Robert Taylor help lead the Concerned Citizens of St. John Parish group.

“Almost every household has somebody that died with cancer or that’s battling cancer,” Mary Hampton, a resident of Reserve, Louisiana who lost multiple loved ones to cancer, told The Guardian in 2019. “It’s the worst thing you’d ever want to see: a loved one, laying in that bed, pining away, dying. Just to sit and look at them, and know you can’t do anything about it.”

In 2024, Human Rights Watch agreed. They published a report in January which found that the approximately 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical plants in Cancer Alley have “devastated the health, lives, and environment of residents.”

‘We’re Dying’: Cancer Alley Today

On Jan. 24, 2024, Human Rights Watch published a 98-page report on Cancer Alley. It declared that the majority-Black residents of Cancer Alley “are the victims of deadly environmental pollution from the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry” and that they “face severe health harms including elevated burdens and risks of cancer, reproductive, maternal, and newborn health harms, and respiratory ailments.”

StoryCenter / YoutubeA protest against Cancer Alley.

From September 2022 until January 2024, Human Rights Watch traveled across Cancer Alley to interview dozens of its inhabitants. Residents shared stories of their “miscarriages, high-risk pregnancies, infertility, the poor health of newborns, respiratory ailments, and cancer” as well as the heartbreaking deaths of friends and family.

The report, which included a study under peer review from Environmental Research: Health, found that people living in areas with bad air pollution had rates of low birth weight more than triple the U.S. average and rates of preterm births almost two-and-a-half times the U.S. average.

People in Cancer Alley also suffered from high rates of “chronic asthma, bronchitis and coughs, childhood asthma, and persistent sinus infections.” Not only that, but their illnesses frequently kept them from work or school and heaped stress onto already high-risk pregnancies.

Human Rights Watch has demanded that the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality increase regulations and enforcement, and that the EPA shut down plants that pose a danger to human health.

But for many people living in Cancer Alley, such a change is already too late. Residents have long suffered from illness and watched loved ones die.

WorldFoto / Alamy Stock PhotoA petrochemical plant near Baton Rouge, Louisiana illuminates the night sky at dusk from behind a local cemetery.

“We’re dying from inhaling the industries’ pollution,” 71-year-old Sharon Lavigne of Saint James Parish said. “I feel like it’s a death sentence. Like we are getting cremated, but not getting burnt.”

After reading about Cancer Alley, see how the Great Smog of London killed 12,000 people in 1952. Or look through these shocking photos of pollution in China’s Yangtze River.