Despite their immense contributions to the civil rights movement, these activists were largely ignored by the history books.

Who are the leaders of the civil rights movement? Certainly, names like Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks come to mind. But it took more than one brave stand to make the movement succeed. It took millions.

These are the unsung heroes of the civil rights movement. They may not have given grand speeches or led marches, but their efforts informed, inspired, and enabled the movement in other ways.

Legal theorists like Pauli Murray helped dismantle discrimination through legislation, and Fannie Lou Hamer, who spoke without notes on live television for 13 minutes to draw attention to the poison of racism.

Many of the civil rights heroes on this list were unknown for reasons that spoke to the cultural and societal flaws of their time. In the male-led civil rights movement, leaders like Dorothy Height were pushed to the side. Others, like Bayard Rustin, were kept out of the spotlight because of their sexuality and political beliefs.

In the end, though, it took people from all backgrounds to move the civil rights movement forward. These heroes may have stood on the sidelines, but their efforts contributed to the movement’s success nonetheless.

Claudette Colvin: The Brave Teenage Civil Rights Leader

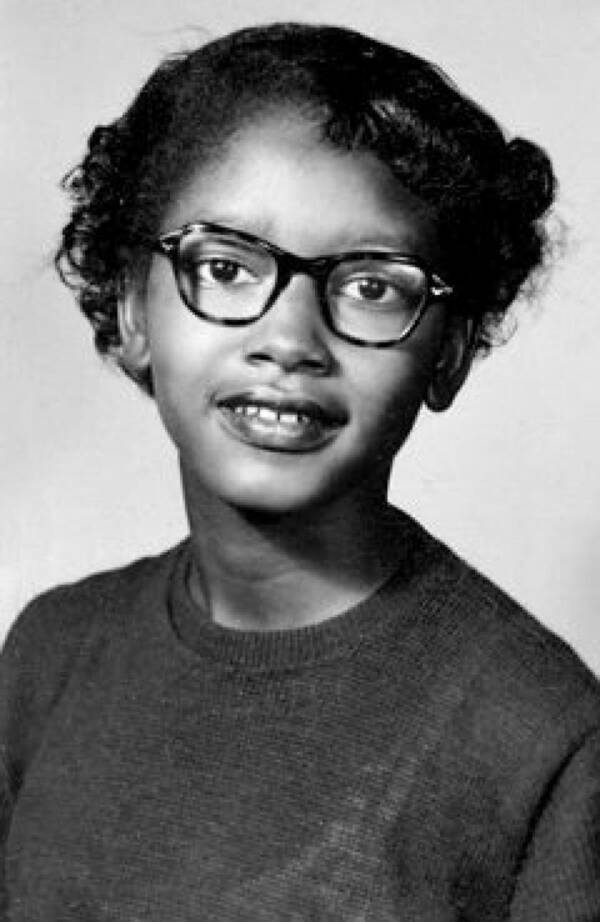

Wikimedia CommonsClaudette Colvin was just 15 years old when she refused to change seats on a segregated bus.

In Montgomery in 1955, a Black girl refused to move to the back of the bus. Sick of segregation, she informed the driver that it was her constitutional right to sit anywhere she pleased. But her name was not Rosa Parks — it was Claudette Colvin.

“History had me glued to the seat,” she later recalled. “It felt as if Harriet Tubman’s hand was pushing me down on the one shoulder, and Sojourner Truth’s hand was pushing me down on the other.”

Just 15 years old at the time, Colvin had spent her young life quietly observing segregation in Alabama. She witnessed powerful injustices, like the execution of her neighbor for allegedly raping a white woman, and smaller ones, like when she tried to buy shoes.

“[Black people] couldn’t try on clothes,” Colvin explained. “You had to take a brown paper bag and draw a diagram of your foot … and take it to the store. Can you imagine all of that in my mind?”

Dudley M. Brooks/The Washington Post via Getty ImagesCivil rights leader Claudette Colvin still vividly remembers her arrest, especially the fear she felt when the police threw her in a jail cell.

By the time Colvin climbed onto a public bus on March 2, 1955, she and her class had started studying influential Black leaders in American history. With their stories racing through her mind, Colvin refused to obey the white driver when he told her to move.

The driver called the police, who dragged Colvin off the bus.

“All I remember is that I was not going to walk off the bus voluntarily,” she continued. Her school books went flying everywhere, and Colvin repeatedly shouted “It’s my constitutional right!”

Despite her brave stand, Claudette Colvin didn’t spark protests like Rosa Parks did. She attributes this to her age, her dark skin tone, and the fact that she got pregnant a few months later.

“They didn’t think teenagers would be reliable,” Colvin recalled.

But Colvin got to have her say a few months later when she testified in Browder v. Gayle, the Supreme Court case that determined bus segregation was unconstitutional. On the stand, a lawyer asked her why she’d refused to move seats.

“Because,” Colvin, then 16, responded, “We were treated wrong, dirty, and nasty.”