"I knew [Clotilda] was out there... It was like you could feel the souls of those people."

Mark Thiessen/National GeographicNails, spikes, and bolts used to secure the beams and planking of the Clotilda that were recently uncovered by archaeologists.

Decades after the importing of slaves from outside the U.S. had been outlawed, the transatlantic trade continued illegally right into the 1860s. It was then that a schooner ship known as Clotilda was the last ship to bring enslaved Africans to America’s shores.

Now, a group of researchers has announced that they have discovered the wreckage from the Clotilda — long thought to have disappeared after it was deliberately destroyed to conceal evidence of its illegal activity — in Alabama’s Mobile River.

According to National Geographic, the captives who arrived in America aboard Clotilda were believed to be the last of an estimated 389,000 Africans who were kidnapped, abused, and sold into slavery from the early 1600s to 1860.

Mark Thiessen/National GeographicA researcher examines wood from the Clotilda in hopes of recovering remnants of captives’ blood.

The discovery is significant for a number of reasons, but namely as the recovery of an important and yet often glossed-over piece of American history. The discovery of the Clotilda has been an anticipated moment by the residents of Africatown, a community of African-Americans who largely descended from the enslaved men and women aboard that ship.

After the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, the Africans, unable to return to their homeland, managed to buy small plots of land north of Mobile, which would eventually be known as Africatown.

The community was built based on the structures that existed in the communities in Africa — they had a chief, schools, laws, and churches. Many of the descendants of the original residents that built Africatown still live in the community today and grew up listening to stories of the slave ship that brought their ancestors to Alabama.

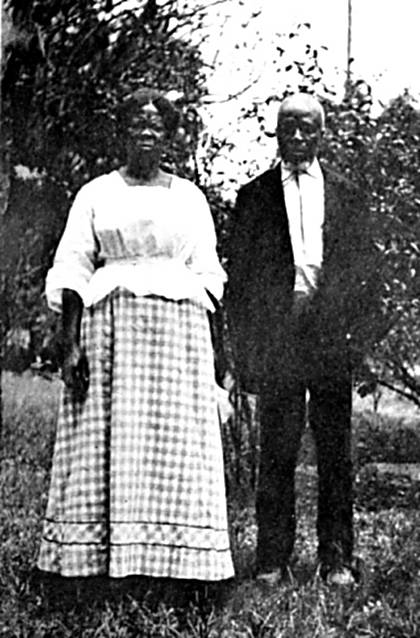

Wikimedia CommonsCudjo Lewis with Abache, another survivor of the Clotilda.

In fact, Cudjo Lewis, the last surviving ex-slave that had been brought from Africa to America was among the thousands of slaves aboard the Clotilda. He later married another survivor from the ship and settled into a farm life existence in Africatown. He died at age 95.

“So many people along the way didn’t think that happened because we didn’t have proof,” 70-year-old Lorna Gail Woods, who learned the story of Clotilda from her mother, told Smithsonian.

“No matter what you take away from us now, this is proof for the people who lived and died and didn’t know it would ever be found.”

Efforts to find the long-lost slave ship by researchers had taken years and involved a massive operation that was only made possible due to the combined efforts of several groups. Authentication and confirmation of the ship’s wreckage were spearheaded by the Alabama Historical Commission and SEARCH Inc., a group of marine archaeologists and divers who specialize in historic shipwrecks.

Also involved were Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Slave Wrecks Project (SWP, which got the residents of Africatown involved in the process.

“This was a search not only for a ship. This was a search to find our history and this was a search for identity, and this was a search for justice,” SWP Co-Director Paul Gardullo explained.

“This is a way of restoring truth to a story that is too often papered over. Africatown is a community that is economically blighted and there are reasons for that. Justice can involve recognition. Justice can involve things like hard, truthful talk about repair and reconciliation.”

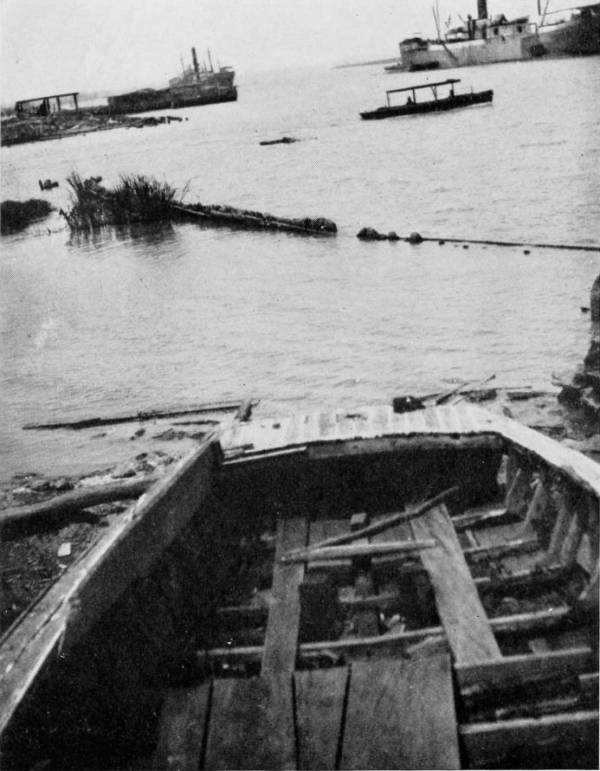

Wikimedia CommonsWreckage of the Clotilda. 1914.

Shipwrecks that were thought to be the remains of the Clotilda have surfaced before. The most recent discovery was by an Alabama reporter last year when extreme low tides in the delta had exposed a previously undiscovered shipwreck.

The fact that it was located right by the island where Captain William Foster, who steered the Clotilda to Africa and back, had burned and sank the ship to cover up the illegal slave run had many convinced that the missing ship was finally found. But after further examination by archaeologists, the wreckage was determined to be a different vessel that was too large to be the Clotilda.

This time, experts are certain that the ship has finally been found. Not only is the discovery of the Clotilda a monumental historical finding, it could very well revitalize Africatown’s dissipating community which has largely been affected by industrial development.

“This is so huge. This could be one of the top tourist attractions in the world once everything is developed in that community,” Alabama State Senator Vivian Davis Figures said of the economic potential for the community.

Figures, who had made trips into the delta with researchers hunting for the vessel before, said that she had held out hope for the discovery to happen.

“I knew [Clotilda] was out there,” she said. “It was like you could feel the souls of those people.”

Now that you’ve read about the recovery of the Clotilda, learn about Sally “Redoshi” Smith, the last known survivor of the Transatlantic slave trade. Then, read about the British Navy’s West Africa Squadron that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade.