When C.P. Ellis was tasked with working with Ann Atwater to desegregate Durham, North Carolina schools, he was an "Exalted Cyclops" of the KKK. Ten days later, he was a strong supporter of the civil rights movement.

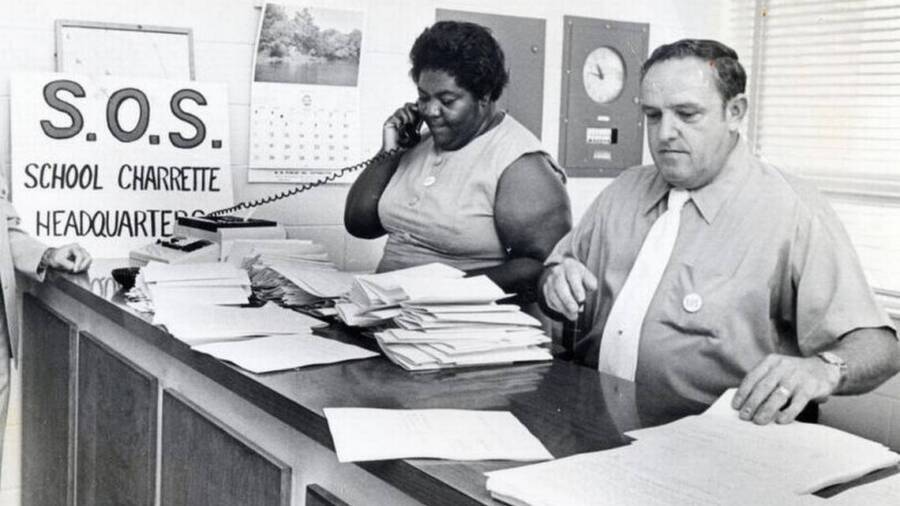

Jim Thornton/The Herald Sun Collections/University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill LibrariesC.P. Ellis, a former Ku Klux Klan leader, with civil rights activist Ann Atwater in 1971.

In 1971, the schools in Durham City, North Carolina, were still segregated. But in an effort to desegregate them, the school district put two bitter enemies in charge of running a 10-day community meeting.

They were Ann Atwater, a Black leader in the city’s civil rights movement, and local Ku Klux Klan leader C.P. Ellis, who found himself on the end of Atwater’s pocket knife one day when he suggested banning Black people from the sidewalks. C.P. Ellis responded by showing up for the community meetings with a machine gun.

But then, something unexpected happened. Ellis not only listened to Atwater, but he began to question his lifetime of racist beliefs. By the end of the meeting, Atwater had convinced Ellis to give up his membership to the KKK — and he became a civil rights advocate.

How C.P. Ellis Became An ‘Exalted Cyclops’

Born the son of a millworker on January 8, 1927, Claiborne Paul Ellis left school after eighth grade to find work to support his family. At 17, he married and went on to have three children who he struggled to feed, working two jobs but barely covering his family’s bills.

“I worked my butt off and never seemed to break even. They say abide by the law, go to church, do right and live for the Lord and everything will work out. It didn’t work out. It kept gettin’ worse and worse. I began to get bitter,” Ellis said in a 1980 interview with Studs Terkel.

That bitterness drove C.P. Ellis to join the Ku Klux Klan, where he believed his frustrations with destitution were heard and understood. But beyond a sense of belonging, the Klan gave Ellis someone to blame for his problems.

“I didn’t know who to blame. I tried to find somebody. I began to blame it on Black people. I had to hate somebody.” Ellis said. “Here are white people who are supposed to be superior to them, and we’re shut out.”

Ellis became a vocal voice for similarly disenfranchised white people in his segregated neighborhood. He quickly became a leader in the Durham chapter of the Klan with a position known as the Exalted Cyclops.

He also became a constant fixture in the civil rights clashes taking place across the country. “I wanted to make them angry,” Ellis recalled of civil rights advocates. “I didn’t like them. I didn’t like integration. I didn’t like the demonstrations downtown.”

And one person, in particular, became the target of C.P. Ellis’s anger. Activist Ann Atwater led boycotts and protests. “She was making progress,” Ellis said. “I hated her guts.”

But Atwater was struggling with many of the same financial difficulties as Ellis and his neighbors. “Mr. Ellis has the same problems with the schools and his children as I do with mine and we now have a chance to do something for them,” Atwater said.

They both considered themselves voices for their communities, and Atwater recognized that if Ellis could see her as someone living with the same struggle, then together they could make a difference.

C.P. Ellis And Ann Atwater Clash

Even though the upshot of the supreme court case Brown v. Board of Education ruled that schools were to desegregate in 1954, by the 1970s, many major school districts still resisted racial integration. Durham was among them.

Nonetheless, in 1971, C.P. Ellis agreed to co-chair a committee on desegregation with Ann Atwater. Wary of his rival, Ellis showed up with a machine gun in his trunk. Ann Atwater also came prepared. “I had my white Bible in my hand,” she said in an interview with NPR. “I always said if they’d said something to me, I was going to knock the hell out of them with my Bible.”

But the rivals soon became unlikely friends.

The shift started almost immediately. During the first few days, the committee listened to a gospel choir. Atwater noticed that Ellis was clapping along. “And he wasn’t clapping his hands even along with us; he would clap an odd beat.”

So Atwater grabbed Ellis’s hand. She “show[ed] him how to clap along with us at the same time till we learned him how to clap.”

Later during the meetings, young people from Durham spoke about their experience. “We talked to the youth, and we found out that the children was the ones suffering,” Atwater recalled.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesIn the 1970s, several school districts resisted desegregation. White parents overturned busses bringing Black children to schools in Lamar, South Carolina, in 1970.

“Me and him was over there mad with each other, but we wasn’t getting anything done that the children wanted.”

It was then that Ellis and Atwater bonded over their shared problems. “Me and him cried at that time,” Atwater said, “and we began to melt down towards one another.”

C.P. Ellis admitted that the experience changed his perspective. “During those days it became clear to me that she had some of the identical problems that I had and that I’d suffered like she had and what in the hell had I spent all my life fighting people like Ann for?”

The Ex Klansmen Becomes A Civil Rights Activist

By the end of the 10-day meeting, C.P. Ellis was ready to renounce his position in the Klan. As he explained,”I found out they’re people just like me. They cried, they cussed, they prayed, they had desires. Just like myself. Thank God, I got to the point where I can look past labels.”

Ellis left the Klan and went back to school. He earned a high school diploma and became a union organizer. By 1980, Ellis was the manager of the International Union of Operating Engineers in Durham, a predominately Black union.

Abandoning the Klan to become an advocate of civil rights saw Ellis ostracized from his friends. He considered suicide, but he stuck to his advocacy.

“I tell people there’s a tremendous possibility in this country to stop wars, the battles, the struggles, the fights between people,” Ellis said in 1980.

“People say: ‘That’s an impossible dream. You sound like Martin Luther King.’ An ex-Klansman who sounds like Martin Luther King. I don’t think it’s an impossible dream. It’s happened in my life. It’s happened in other people’s lives in America.”

C.P. Ellis and Ann Atwater remained friends for decades, and according to Atwater, they “looked after each other.” When Ellis died in 2005 from Alzheimer’s disease, Atwater delivered his eulogy.

After this look at the galvanizing friendship of Ann Atwater and C.P. Ellis, learn about nine unsung leaders of the civil rights movement. Then, discover the story of Ella Baker, the “mother” of the civil rights movement.