Source: NY Post

Humans are designed to compartmentalize objects, ideas, and experiences. It’s how we survive. Our early ancestors’ ability to instantaneously decide a whether a situation was safe or dangerous was imperative if they wanted to keep their weak, hairless little bodies alive long enough to pass along their genes.

As societies developed, understanding our place within that structure, as well as everyone else’s, became just as important. We wanted to look at somebody and immediately know certain things about them (namely, were they trying to have sex with us, and were we trying to have sex with them). We would use visual cues to gather information about a person and tailor our behavior accordingly.

That is one of the reasons why crossdressing, and those who crossdress, are often met with derision, distrust, and even distaste. Crossdressers disrupt our ability to separate people into neat categories and force us to confront the reality that gender groupings, and consequently gender itself, are largely imaginary.

This article features a sampling of crossdressers–famous, infamous, and unknown–from around the world and across time. We hope it sheds some light onto this often misunderstood group.

Crossdressing History: Ancient Scandinavia

Source: Pinterest

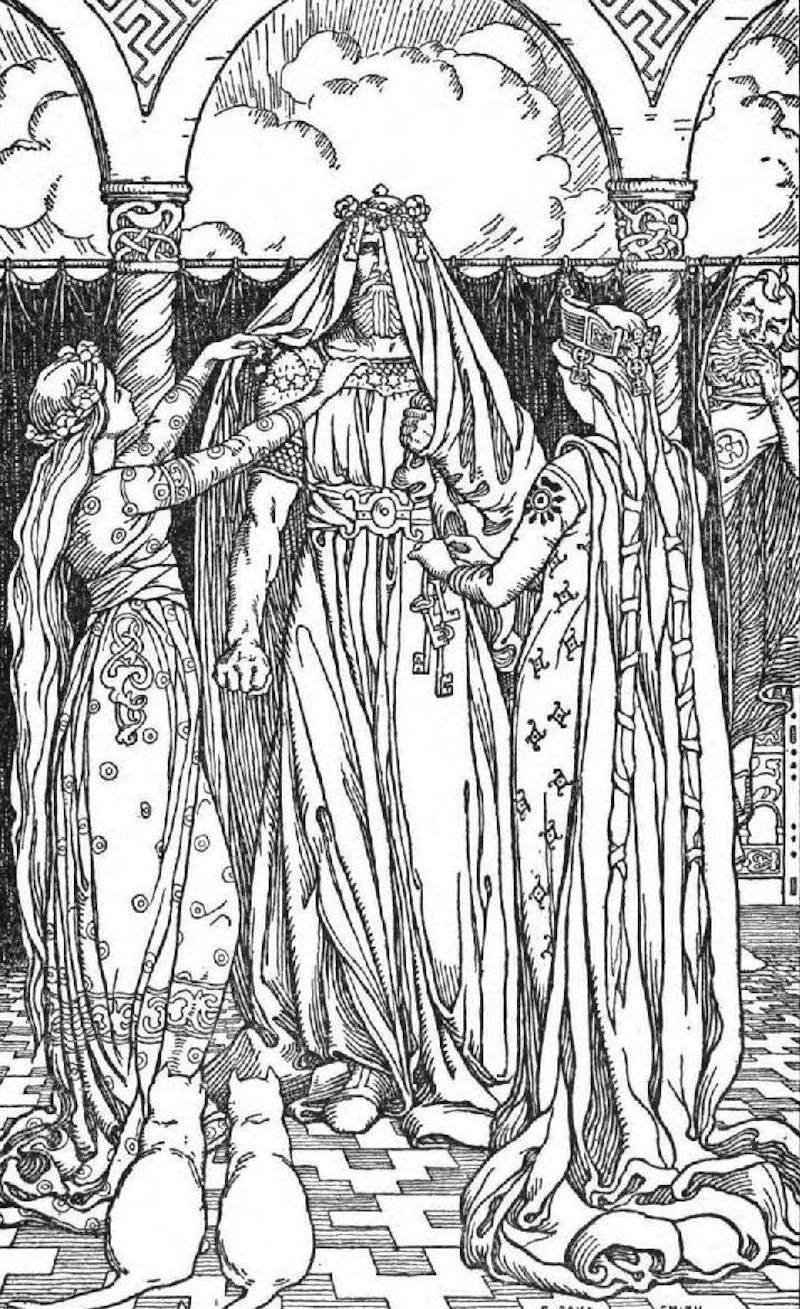

According to Norse mythology, Thor and Loki were two of the earliest crossdressers known to man. Nobody knows the exact year that Icelandic people began telling this story. It wasn’t written down until the 11th century CE, but its oral equivalent had likely existed for hundreds–even thousands–of years.

The story goes like this: Thor wakes up one morning to find that Mjölnir (his hammer) has been stolen by Thrymr the Giant. Thrymr is willing to trade Mjölnir back to the gods, but in exchange he wants a wife.

Specifically he wants Freyja, the Norse Goddess of love, sexuality, beauty, fertility, gold, war, and death. Thor and Loki tell Freyja to go put on a white dress and marry Thrymr The Giant. She tells them she will do no such thing, and then she drives away in her chariot pulled by two giant cats. So Thor and Loki decide to just do it themselves. With the help of the other gods they dress up as women–Thor as Freyja, and Loki as her handmaid–and off they go to the wedding.

When they arrive, Thrymr is shocked to see his bride “eat enough for thirty men.” Loki tells Thrymr that “Freyja” is simply so excited to be married that she has not eaten in over a week. When the giants place Mjölnir in “Freyja’s” lap as a part of the wedding ceremony, Thor rips off his veil and slaughters every single giant in the hall.

Late Sui–Early Tang Dynasties, China

Source: House Of Geekery

Disney didn’t invent the story of Hua Mulan, the devoted daughter who joined the army to defeat the Huns in her elderly father’s place. It’s existed since the 6th Century CE when a poem titled The Ballad Of Mulan was written.

While the poem would seem to support the idea of gender equality and fluidity, most scholars agree that the main theme is war’s effects on society, and Mulan’s crossdressing is simply a manifestation of that chaos.

By the end of the ballad, the war is over, and life is good again. Mulan returns home and reasserts her feminine gender identity. She re-applies her makeup, arranges her “cloud-like hair,” dresses in women’s clothing again, and society returns to “normal”.

While the poem may not work towards dismantling gender constructs, many of the musical numbers in Disney’s Mulan pose a few interesting questions: what does it mean to be a man? What does it mean to be a woman? Are these two categories inherently distinct?

Elizabethan England

Source: Penny Arcade

Only thirty-eight of Shakespeare’s original plays survive today. Out of those thirty-eight plays, seven feature crossdressed characters: The Merchant Of Venice, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Cymbeline, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Taming of the Shrew, and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Most often it’s a female character adopting male clothing and mannerisms, and she usually crossdresses for protection, since it wasn’t safe for a woman to travel alone in Shakespeare’s day. These characters tend to exist in a type of third gender category between male and female.

In Twelfth Night, Viola (crossdressed as her brother, Sebastian) becomes the object of desire for both Olivia (a woman) and Duke Orsino (a man), because she is more sensitive, intuitive, and understanding than the average man. Similarly, male-to-female crossdressed protagonists are often viewed as “ideal women” because they are thought to be tougher, stronger, and more decisive than the average woman.

To add another layer of confusion to the whole thing, women were not allowed to perform on stage in Elizabethan England. Men played every role. So if you think about it, each of these crossdressed characters would’ve been a man, pretending to be a woman, pretending to be a man.

Source: Wikipedia

A hundred or so years later, molly-houses would become an important part of the homosexual subculture in England. “Molly” referred to an effeminate, usually homosexual, male, and molly-houses were male brothels. Many employees and patrons of these establishments engaged in crossdressing, even though they were severely persecuted for it.