The Cultural Revolution was one of the bloodiest eras in China's history in which 1.5 million people died — and it lasted but 10 years.

"The Cultural Revolution," the Chinese Communist party wrote just five years after Communist leader Mao Zedong's reign had ended, "was responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the party, the state and the people since the founding of the People's Republic."

In the decade between 1966 and 1976, China was in the throes of a passionate cultural upheaval. Under the guise of purging the Communist party of bourgeois attitudes and complacency, Chairman Mao Zedong mobilized the youth to reassert his power in China.

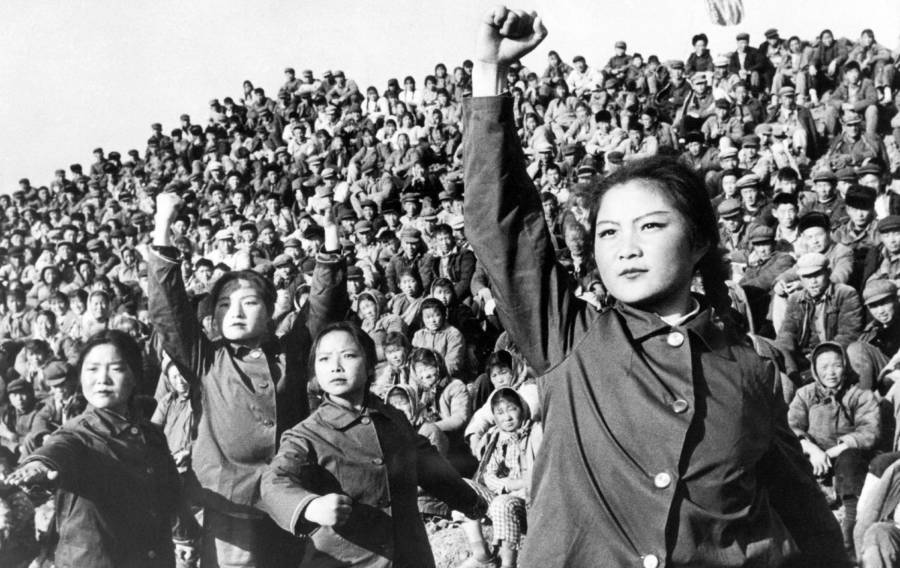

His plan worked. Young people in military uniforms and red armbands dragged their teachers and their neighbors into the streets and publicly beat and humiliated them in an attempt to eradicate the country of traitors to the party. The youths went into ancient temples and smashed sacred relics in order to bring China into a new age free of old ideas. They waged a war against what they believed was the creeping presence of the bourgeoisie — all in the name of Mao.

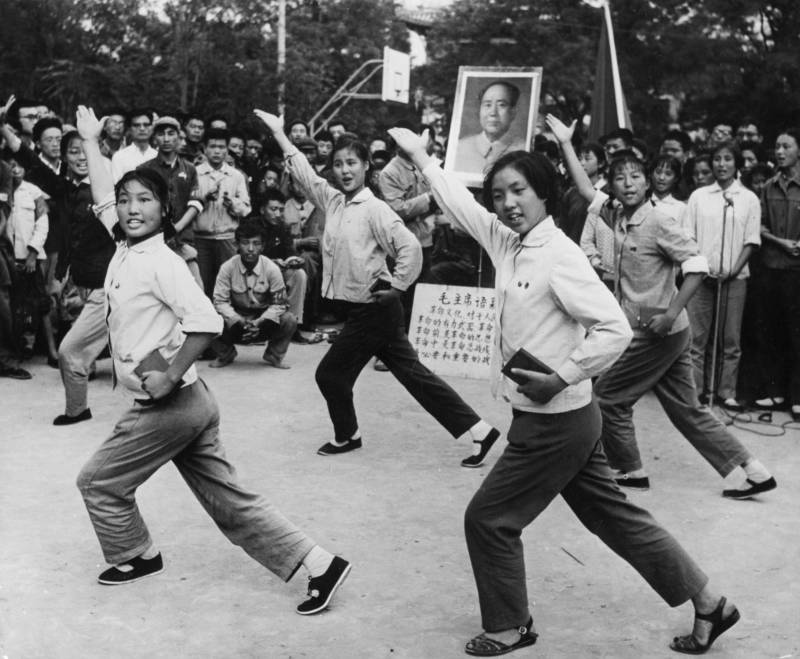

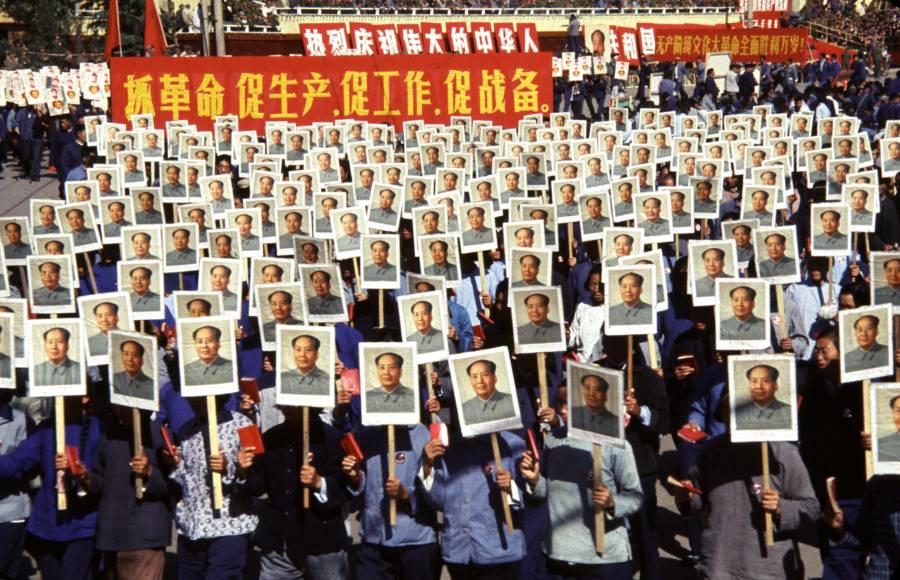

"We all shared the belief that we would die to protect Chairman Mao," 64-year-old Yu Xiangzhen recalled to the Guardian. "Even though it might be dangerous, that was absolutely what we had to do. Everything I had been taught told me that Chairman Mao was closer to us than our mums and dads. Without Chairman Mao, we would have nothing."

Such was the time of the Cultural Revolution in China - and it was one of the strangest and most dangerous times to be alive there.

Wikimedia CommonsRed guards at No. 23 Middle School wave the Little Red Book of the Quotations of Chairman Mao in a classroom revolution rally.

The Cultural Revolution Begins

From 1958 to 1962, Mao launched an economic campaign through which he hoped to turn China away from an agrarian-based society and into a more modern, industrial one. The campaign was known as the Great Leap Forward, and it was a great failure. As such, Mao's power in his party and in his country was greatly weakened.

In an attempt to again garner support, Mao called for a great reformation that would oust those who doubted him from power and reinstate his reign. On May 16, 1966, Mao Zedong released what would come to be known as the May 16 Notification, and it was on that day that the Cultural Revolution began.

The bourgeoisie, Mao warned the people of China, had snuck into the Communist party. "Once conditions are ripe," he wrote, "they will seize power and turn the dictatorship of the proletariat into a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie."

The People’s Republic was under attack, Mao claimed, by revisionist Communists. In essence, the message warned that Chinese politics had been corrupted by insufficiently revolutionary individuals. The party could not trust anyone, even those within it. The only way forward, Mao urged, was to find those traitorous individuals who did not adhere to Maoist Thought. What ensued would be a bloody class struggle.

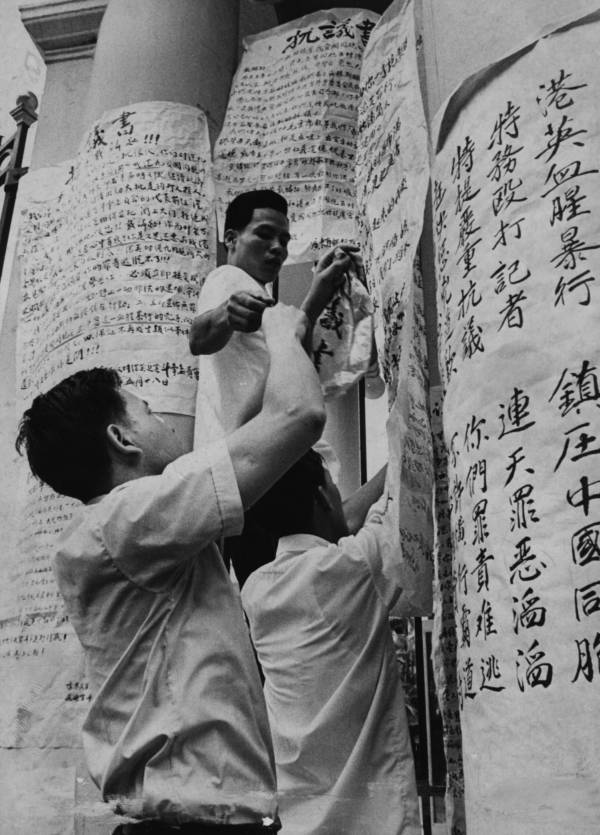

The youth of China answered his call. Within days, the first Red Guards — or paramilitary groups — were formed. They were students at Tsinghua University High School who set up massive posters, publicly accusing their school’s administration of elitism and bourgeois tendencies.

Mao was pleased. He had their manifesto read on the airwaves, publicly went out wearing their red armband, and ordered his police not to interfere with any of their activities no matter how violent they became.

The students turned violent indeed. The Red Guard went out chanting slogans like: "Swear to fight to the last drop of our blood to defend Chairman Mao’s revolutionary line" and "Those who are against Chairman Mao will have their dog skulls smashed into pieces."

Their teachers were brutally beaten in the name of Mao's revolution. "I believed it," Yu said of the Chairman's harsh mission, "I thought Mao Zedong was great and that his words were great."

But Yu, who served in the Red Guards as a youth, also recalled the terror of her teachers being brutalized.

"Each time we fell asleep the screams woke us up. The screaming never stopped."

Yu's teacher was only one of many to suffer that fate. Between August and September 1966 alone, 1,722 people were murdered by the Red Guards in the city of Beijing.

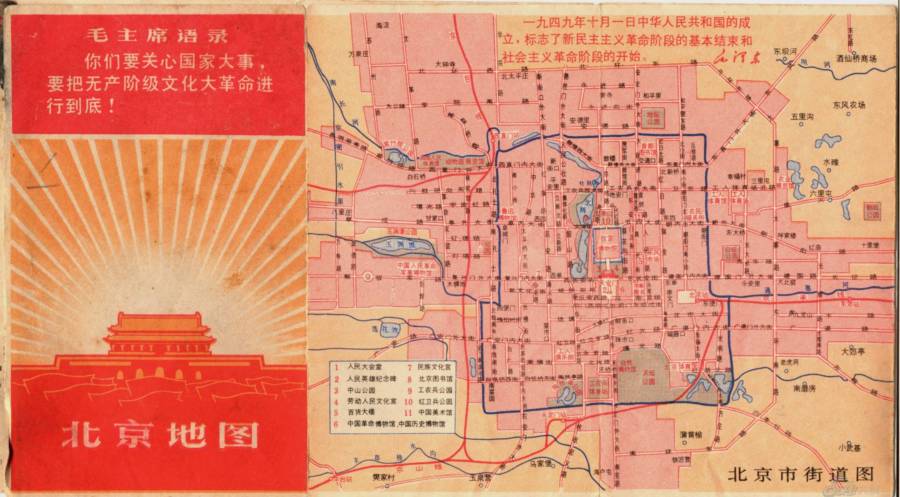

Wikimedia CommonsA map of streets and landmarks renamed in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution.

Destroy The Four Olds

"Sweep away all monsters and demons," an editorial in the party's newspaper People’s Daily read on June 1, 1966. "Smash the bourgeois 'specialists,' 'scholars,' 'authorities,' and 'venerable masters.'"

The article called on the people to destroy "the Four Olds:" old ideas, old cultures, old customs, and old habits that it has said had been fostered by the exploitative rich to poison the minds of the people.

All of history, in short, was to be seen as useless. This was the central meaning of Cultural Revolution: That China was going to destroy every trace of its bourgeois past and replace it with a new culture built on the principles of Maoism and Marxism. Communist leaders like President Liu Shaoqi were taken out of power and replaced with men Mao believed were not critical of his reign.

The people carried with them a Little Red Book, a plastic red collection of Mao's ideologies. Yu even recalled reading and studying it with her friends while on commutes as though it were a Holy Bible. Streets, historical sites, and even babies were given new, revolutionary-sounding names. Libraries were destroyed, books were burned, and temples were torn down to the ground.

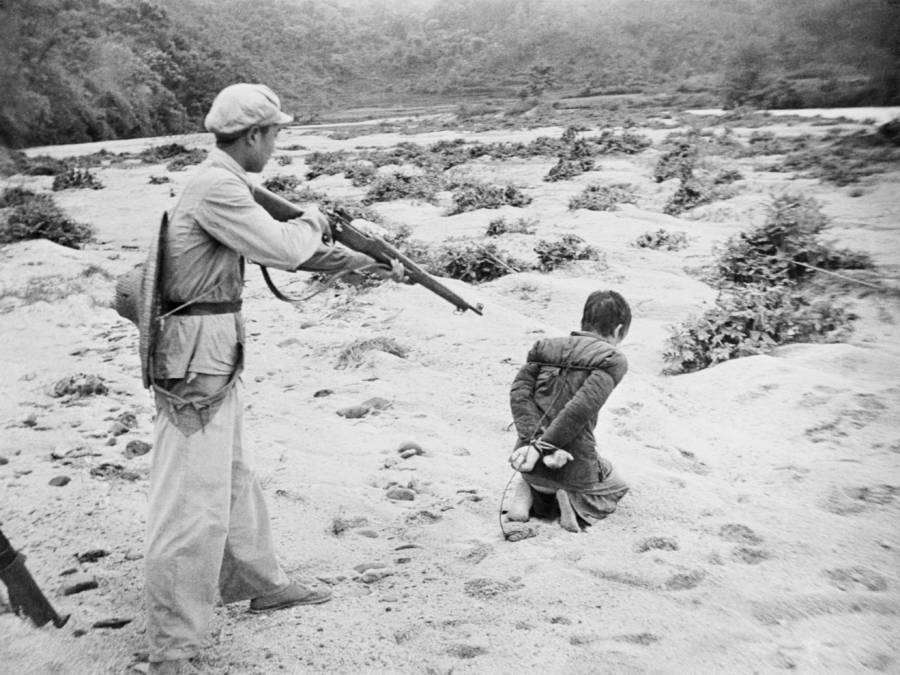

Historical sites were ripped apart. In Shandong, the Red Guards attacked the Temple of Confucius, destroying one of China’s most historically significant buildings; in Tibet, soldiers forced Buddhists priests to destroy their own monasteries at gunpoint.

A new world, Mao promised, would rise from the ashes of the old one; one that swept away every hint of elitism and class inequality.

Perhaps to prove he was as good as his word, Mao began the Up to the Mountainside and Down to the Countryside Movements on the late 1960s, which saw the forcible transfer of 17 million urban youths, most of them well-educated students, out of the cities in which they lived and into farms on the countryside.

Schools were shut down altogether. The University entrance exam was abolished and replaced with a new system that pushed students into factories, villages, and military units.

Struggle Sessions

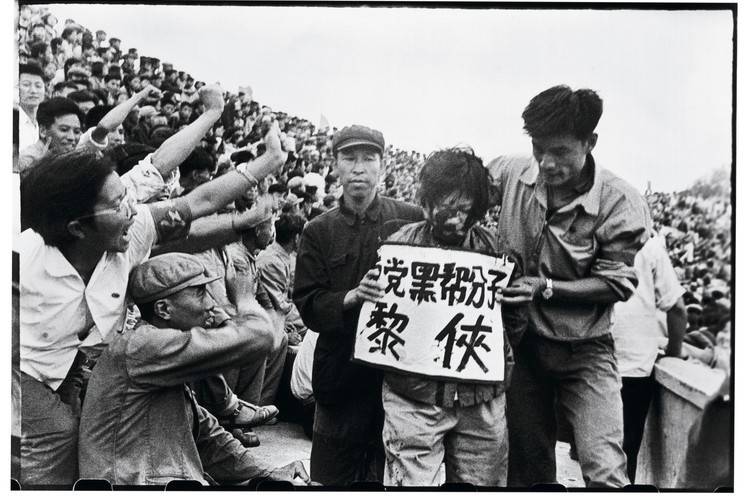

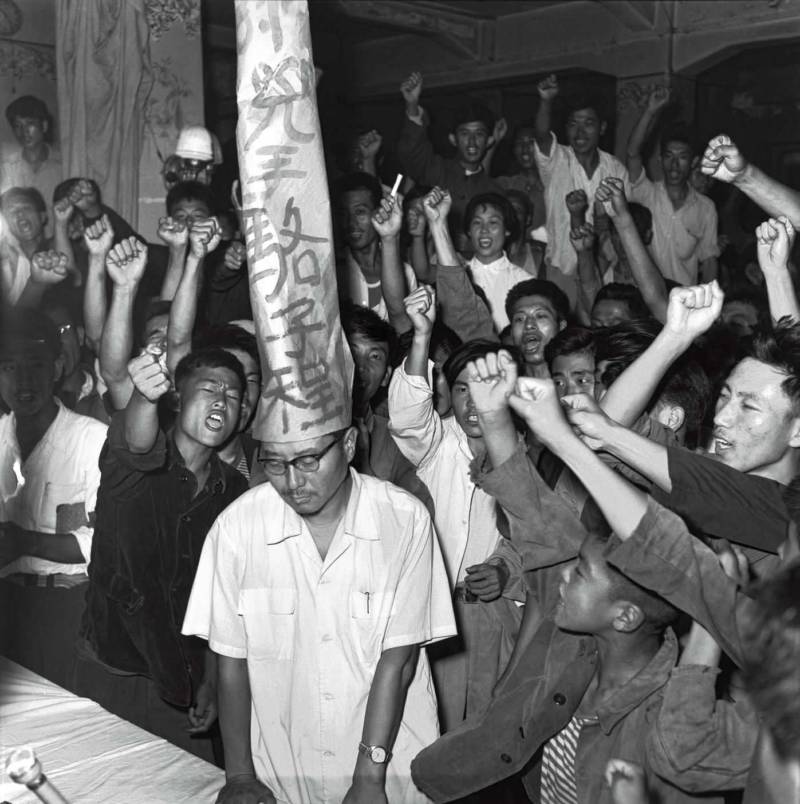

TwitterA man endures a struggle session.

The darkest moments of all of the Cultural Revolution, however, were the "struggle sessions".

The people of China were urged to get rid of every bourgeoisie in their midst including scholars, traditionalists, or educators. People were accused by their neighbors of counter-revolutionary crimes and forced them to endure public humiliation or even death.

Victims would be forced to wear massive bamboo hats with their crimes written on them and drape big signs around their necks with the names crossed out with a red X. Before a jeering crowd, they would be forced to confess to their bourgeoisie crimes. If not, they would be beaten, sometimes to death.

One survivor recalled the near-death of a friend in graphic detail:

"You Xiaoli was standing, precariously balanced, on a stool. Her body was bent over from the waist into a right angle, and her arms, elbows stiff and straight, were behind her back, one hand grasping the other at the wrist. It was the position known as 'doing the airplane.'

"Around her neck was a heavy chain, and attached to the chain was a blackboard, a real blackboard, one that had been removed from a classroom at the university where You Xiaoli, for more than ten years, had served as a full professor. On both sides of the blackboard were chalked her name and the myriad crimes she was alleged to have committed.

"...In the audience were You Xiaoli's students and colleagues and former friends. Workers from local factories and peasants from nearby communes had been bused in for the spectacle. From the audience came repeated, rhythmic chants...'Down with You Xiaoli! Down with You Xiaoli!'

"... After doing the airplane for several hours, listening to the endless taunts and jeers and the repeated chants calling for her downfall, the chair on which You Xiaoli had been balancing was suddenly kicked from under her and she tumbled from the stool, hitting the table, and onto the ground. Blood flowed from her nose and from her mouth and from her neck where the chain had dug into the flesh. As the fascinated, gawking audience looked on, You Xiaoli lost consciousness and was still.

"They left her there to die."

Aftermath

Just two years into the Cultural Revolution and industrial production had dropped 12 percent below that of the year it had begun. By the end of China's Cultural Revolution, an estimated 729,511 people were persecuted in struggle sessions. 34,800 of them were killed. It's estimated that as many as 1.5 million people were killed during the Revolution.

The Cultural Revolution was a horrific time in China's history, though its name suggests something entirely different — an Enlightenment perhaps. In reality, though, it was a time when the country seemed to have gone mad. For 10 years the struggle sessions and revolts carried on which crushed through Chinese life relentlessly as Chairman Mao implored of his people:

"The world is yours, as well as ours, but in the last analysis, it is yours. You young people, full of vigor and vitality, are in the bloom of life, like the sun at eight or nine in the morning. Our hope is placed on you. The world belongs to you. China's future belongs to you."

With Mao's death in 1976 and the Chinese government switching between facets of Communist powers, the Cultural Revolution came to an end. The education systems which Mao had eradicated during the Revolution were reinstated, though the Chinese people's faith in their government was not and the country would feel the effects of this tumultuous decade for decades to come.

Next, learn about the horrors of the Rape of Nanjing and the Muslim reeducation camps that still operate today.