In 1698, Scottish colonists set sail to modern-day Panama with the goal of building a settlement there. But the plan turned out to be a total disaster.

England spent the late 1600s building its empire — a famously powerful realm that would expand all over the world and last for centuries. But just to the north, Scotland was in ruins.

Decades of warfare and famine had ravaged the kingdom, and its economic situation was dismal. To make matters worse, the country seemed to be nearing the end of its long independence.

By 1698, both England and Scotland were ruled by King William III — who had forcibly deposed James II and VII. As Scotland sensed its sovereignty slipping away, it was desperate to stave off English rule and retain its power.

Wikimedia CommonsIn the late 17th century, Scotland was in financial ruins and desperate to stay independent.

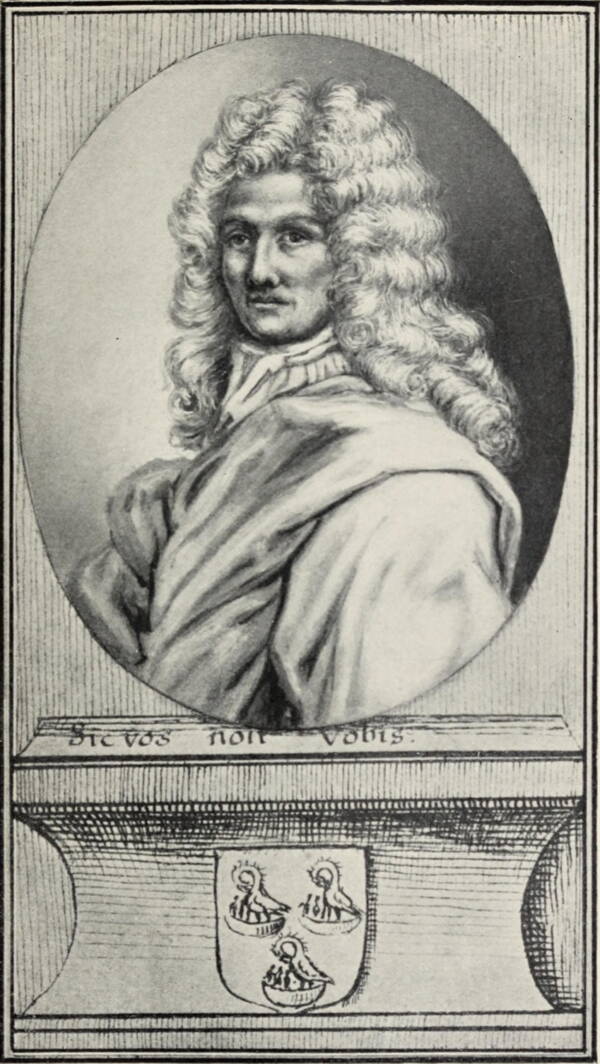

Scotland’s solution was to take up the ideas of William Paterson, a banker and merchant who advocated for establishing “New World” colonies — like those founded by England — to revive the country’s fading fortunes.

Paterson’s ideas resulted in an attempt to establish a colony by the Gulf of Darién, in what is now Panama. But the colony ended in utter failure, bankrupting the kingdom and forcing it to give up its independence.

This is the story of the end of Scottish autonomy, the rise of the United Kingdom, and the devastation left in the wake of Scotland’s Darién scheme.

The Origins Of The Darién Scheme

Wikimedia CommonsScottish merchant and banker William Paterson successfully founded the Bank of England in 1694, but his plans for a colony in Panama devastated his homeland.

Born in Scotland in 1658, William Paterson didn’t remain in his homeland for long. Fleeing religious persecution at the age of 17, he emigrated first to England, and then later to the Bahamas. By some accounts, he made a living there as a preacher, while others have characterized him as a buccaneer.

But his time in the Bahamas changed the course of Scottish history forever. While there, he learned of the Isthmus of Darién (now the Isthmus of Panama), where North America and South America join together in a thin strip of land, with the Atlantic on one side and the Pacific on the other.

Realizing that a colony at this site could speed up global trade by serving as a gateway between the two oceans, Paterson returned to Europe. Over the course of several years, he unsuccessfully promoted his plan for a bustling Panamanian trade hub in England and a few other countries.

Alternately ignored or rejected, Paterson returned to England and focused his attention on trade. He also established the Bank of England, which would ultimately go on to be his most successful project.

He founded the bank in 1694 and served as its director for just one year before he withdrew from the post following a disagreement with his colleagues. After leaving the bank, he turned his full attention toward his “Darién scheme.”

During this period, Paterson’s native Scotland was being rapidly left behind by the rest of Europe. Its small, underdeveloped economy was no match for England or the other trading empires of the continent.

However, King William did decree that Scotland would be allowed to raise funds for establishing its own colonies. Paterson saw his chance.

Returning to his homeland, Paterson soon won over the public with dreams of fabulous wealth gained from Panamanian trade. In 1695, he established the Company of Scotland (which was modeled after the English East India Company), and opened its doors for business.

The Perilous First Expedition To Panama

Wikimedia CommonsIn 1698, the first ships carrying Scottish colonists set off for Panama — unaware of the danger that lay ahead.

Paterson’s company needed to be funded by public investment — and the Scottish public was more than happy to help. Eager to revive their flailing nation, ordinary Scots rushed to invest their meager funds in the effort. Even the poorest people contributed what little they could spare. In a matter of months, roughly £400,000 had been raised.

This money represented about a fifth of the total wealth in impoverished Scotland. It was used to outfit and equip five ships, Saint Andrew, Caledonia, Unicorn, Dolphin, and Endeavour. These ships carried about 1,200 settlers, including William Paterson and his family. If the Darién colony succeeded, then the company hoped to establish more colonies all over the world.

In July 1698, the Darién fleet sailed out of Scotland and across the Atlantic. Unfortunately for Paterson, he found out that one of his “friends” had absconded with more than £8,000 of the company’s money.

Forced out of his leading role in the plan, Paterson was only allowed to travel as a private individual along with his family. He no longer had the power to direct the scheme that he had promoted for years.

The settlers reached the Gulf of Darién in November. Despite none of them having any knowledge of the area, they established the colony of “New Caledonia” and began building a settlement called “New Edinburgh.”

Wikimedia CommonsWith the Pacific on one side and the Atlantic on the other, the site of “New Caledonia” was chosen as a supposedly ideal place for a Scottish colony.

Paterson and the settlers planned to build a robust outpost, forge alliances with the local Indigenous peoples, fend off Spanish colonists in the area, and usher in a new era of prosperity and wealth for Scotland.

But their high hopes were almost immediately dashed. The food that they’d brought along had rotted, the crops that they’d planted failed to grow properly in a new environment, and the settlers were soon struck with disease. Hundreds died, including Paterson’s wife and child.

Many of the colonists who survived these setbacks were forced to live on less than one pound of flour per week — and it was moldy. One man wrote, “When boiled with a little water, without anything else, big maggots and worms must be skimmed off the top.”

Much to the surprise of the settlers, the local Indigenous population had no interest in trading with them. And the Scots soon found out that England had forbidden all English ships and colonies from trading with or supplying the new Scottish settlement. They also learned that nearby Spanish colonists were plotting a devastating attack on New Caledonia.

Cut off from potential allies and helpless to defend themselves, the surviving settlers decided to abandon the colony, barely escaping in July 1699. Of the original 1,200 settlers, only 300 of them came back to Scotland alive.

The Catastrophic Effort To Support The Colony

Wikimedia CommonsThis chest was used to carry documents and money for the establishment of the Darién colony.

Since news traveled slow in those days, Scotland was unaware of the failure of the first mission. So as the first colonists were traveling back, the country was already sending a second expedition on the same ill-fated journey.

Only after the original settlers had reached safety did they learn that more ships — carrying about 1,300 colonists — were on their way to the abandoned colony, completely ignorant of the danger.

This new group of settlers landed in November 1699, finding only graves and abandoned huts left behind. Threatened by hundreds of Spanish militiamen, they were forced to huddle within a hastily-rebuilt fort.

Although the colonists defeated the Spanish attackers under the leadership of Captain Alexander Campbell, the arrival of five Spanish warships carrying hundreds of more soldiers put an end to their defense.

Devastated by sickness, lack of supplies, and minimal ammunition, the Scots were forced to surrender in March 1700.

Only a “handful” of settlers from the second expedition made it back to Scotland alive. Many of those who did not return had died of disease, starvation, or battle wounds. Others had been sold into indentured servitude, shipwrecked, or drowned while attempting to escape.

In less than two years, Scotland’s economy had been completely devastated by its colonization efforts. And tragically, almost everyone in the country had lost a friend or family member to the failed scheme.

How The Darién Scheme Changed Scotland

Wikimedia CommonsIn 1707, a destitute Scotland joined England to form the United Kingdom under the rule of Queen Anne.

If Scotland had been in a desperate situation when it first conceived of the colony, it was in dire straits following its failure. With the collapse of the Darién scheme, the country’s million inhabitants were now facing disaster.

The loss of the nation’s wealth and most of the ships of the tiny Royal Scots Navy had pushed public faith in Edinburgh’s parliament to catastrophic lows. Suddenly, access to English markets, money, and colonies seemed far more appealing, with the hope that English bankers might mercifully wipe out the now-staggering debts faced by Scotland.

In 1707, the two parliaments negotiated the Acts of Union, combining Scotland and England into the United Kingdom under the rule of Queen Anne. As part of the terms, the English government demanded that the Company of Scotland be dissolved. In return, Scotland received a relief package of more than £395,000, restoring it to financial security.

The nightmare of the Darién collapse had ended. But some Scots weren’t pleased with their government’s decision and believed their sovereignty had been “bought and sold for English gold.” After all, centuries of Scottish independence — which many Scots were proud of — were now over.

William Paterson returned to Britain in December 1699, where he recovered from an illness he’d contracted in Central America. He lived out most of his remaining years in poverty, until he was granted a payout in 1715. He used this to support himself until his death in 1719.

Today, the Darién scheme is remembered as the last gamble of a country falling swiftly under the control of the British Empire. Ironically, following this failed attempt to use colonialism to solve its problems at home, Scotland became the source of many of the empire’s most active colonizers, such as Sir John MacDonald, the first Prime Minister of Canada.

And nearly 200 years after the Scottish failed to establish trade by the Gulf of Darién, construction on the Panama Canal began in 1881. Completed in 1914, the canal is still considered an engineering marvel. It also proves that Paterson’s dream to transform the Panamanian isthmus into a major trade route did work — just not when Scotland needed it the most.

Now that you’ve learned about the disastrous Darién scheme, find out how archaeologists may have finally uncovered the truth of what happened to the lost colony of Roanoke. Then, read about Henry Morgan, who terrorized the Caribbean in the Golden Age of Piracy.