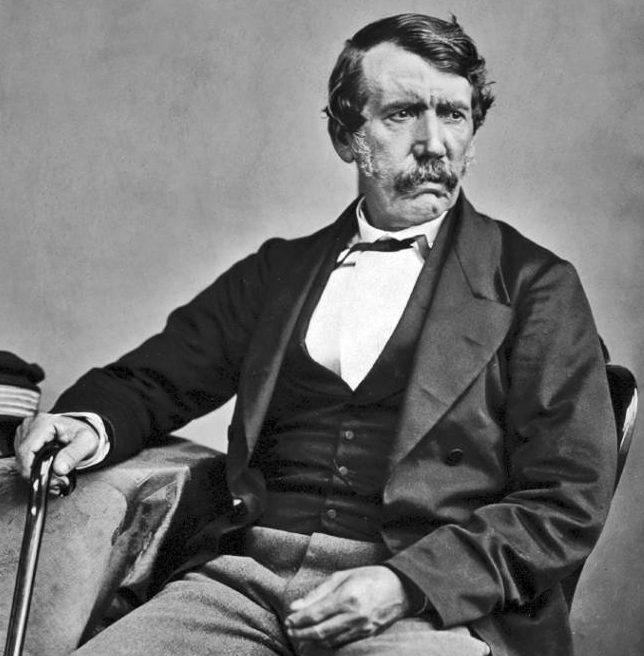

David Livingstone went farther than any European had gone in Africa in European history, but his explorations would have devastating consequences.

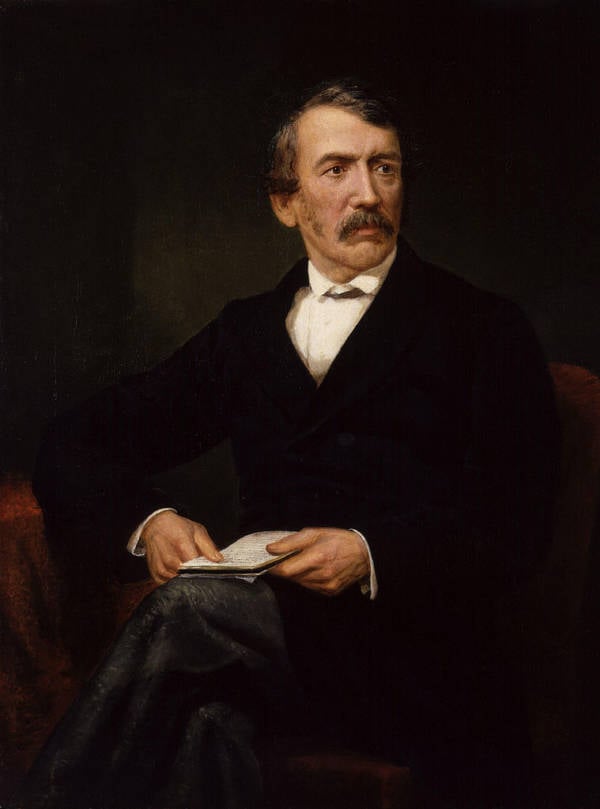

Wikimedia Commons1861 portrait of David Livingstone

Scottish missionary David Livingstone landed in Africa with the desire to spread his zealous Christian tradition as a means to free the country of slavery. Instead, Livingstone begat a legacy of missionaries and colonialists alike who swarmed the country indiscriminately for land and resources in what is now known as “the scramble for Africa” of the late 19th century.

Early Life

David Livingstone’s early childhood reads like a Charles Dickens novel, albeit one set in the Scottish Highlands rather than the streets of London. Born on March 19, 1813, in Blantyre, Scotland Livingstone and his six siblings were all raised in a single room in a tenement building that housed the families of employees of the local cotton factory.

By the time he was ten, Livingstone worked at the factory himself. David’s parents, Neil and Agnes, were both religious zealots and strongly emphasized the importance of reading and education as well as instilled in him discipline and perseverance.

Livingstone’s endurance would be tested in Africa, but a hard childhood had prepared him.

David Livingstone then attended the village school despite his 14-hour work days. When in 1834, British and American churches sent out an appeal for medical missionaries to be sent to China, he decided to apply. After four years of studying Latin, Greek, theology, and medicine, he was accepted by the London Missionary society.

By the time Livingstone was ordained in 1840, travel to China had been made impossible by the opium wars and so Livingstone set his sights on Africa instead, a twist of fate that would seal his place in British history.

David Livingstone’s Abolitionist Mission

In 1841 David Livingstone was posted to a mission in Kuruman, near the Kalahari desert in southern Africa. It was there that he was inspired by fellow missionary Rober Moffat — whose daughter Livingstone would we in 1845 — and became convinced that it was his life’s mission to not only spread Christianity to people all over the continent but to liberate them from the evils of slavery.

Livingstone’s religious background had turned him into a fierce abolitionist. Though the Atlantic slave trade had been abolished in both Britain and America by 1807, the people who populated Africa’s East Coast were still seized by Persians, Arabs, and traders from Oman. Livingstone decided to devote himself to the eradication of slavery from the entire continent and was convinced that carving a path from the East to West coast, something which had not yet been done in recorded history would be the way to do it.

Wikimedia CommonsBy the time Livingstone returned to England after his first explorations in Africa, he was an international celebrity.

Making His name In Africa

By 1852, Livingstone had already ventured further north into Kalahari territory than any other European at that point.

Even in is first explorations, David Livingstone displayed a knack for befriending the native people, which was often the difference between life and death for an explorer. Further, Livingstone traveled light. He brought few servants or help along with him and bartered along the way. He also did not preach his mission on those reluctant to hear it.

A turning point came in 1849 when he was given an award by the British Royal Geographical Society for his discovery of Lake Ngami. With the support and funding of the society, Livingstone would be able to undertake more dramatic adventures and in 1853 he declared that “I shall open up a path into the interior, or perish.”

He set out from Zambezi on Nov. 11 1853, and by May the following year, he made good on his vow and reached the West Coast at Luanda.

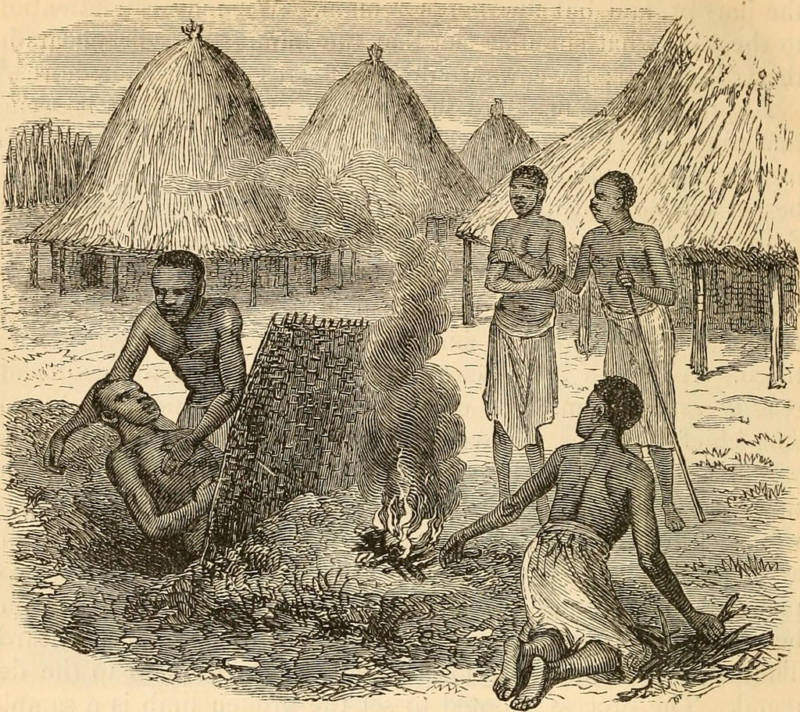

Flickr CommonsLivingstone captured the public’s imagination with public recounts of his travels.

Over the next three years, Livingstone racked up more accomplishments. He discovered the Victoria Falls in November of 1855 for which he named it after England’s reigning monarch. By the time he returned to England in 1856, he was a national hero who was feted all over the country and mobs of fans flocked to him on the streets. His adventures in Africa, however, were far from over.

Livingstone Explores The Origins Of The Nile

The origins of the Nile had been a mystery since ancient times. The Greek historian Herodotus launched the earliest documented expeditions to find the river’s source in 461 B.C., but nearly two thousand years later, it still had not been found. Yet David Livingstone became convinced that he would be the one to crack the enduring mystery.

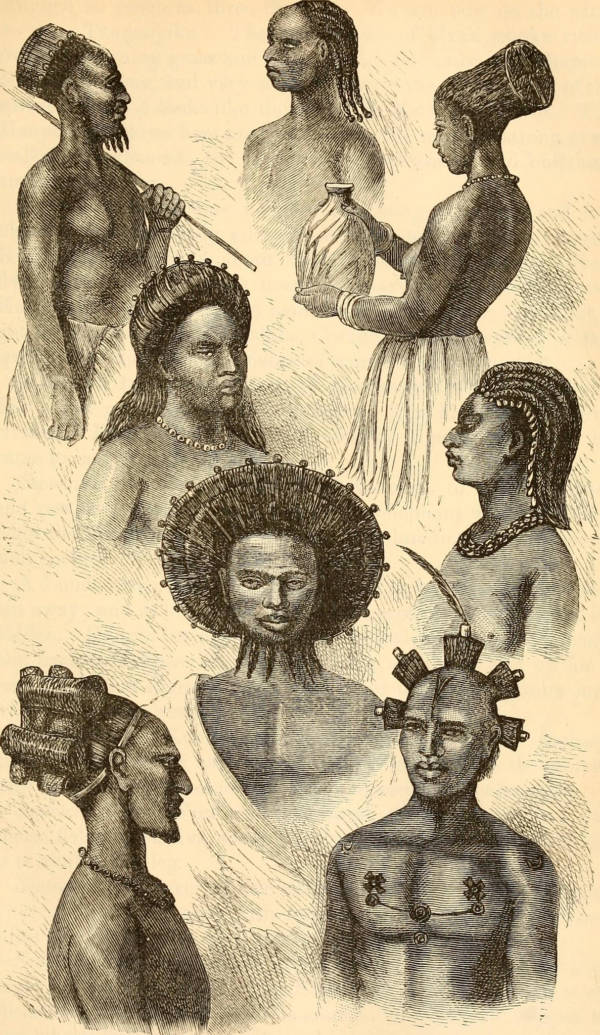

Livingstone’s descriptions of the people he encountered in Africa fascinated the British public.

In January of 1866, with the backing of the Royal Geographic Society and other British institutions, David Livingstone set out with a small group from Mikindani on Africa’s east coast.

The journey was fraught with drama from the start and, when a group of his followers suddenly returned and claimed he had been killed, it seemed that he too had failed in this insurmountable task. Livingstone was very much alive, however, his followers had made up the story for fear of punishment at abandoning him. He was desperately ill and one of the deserters had made off with his medical supplies, but he had not abandoned his quest.

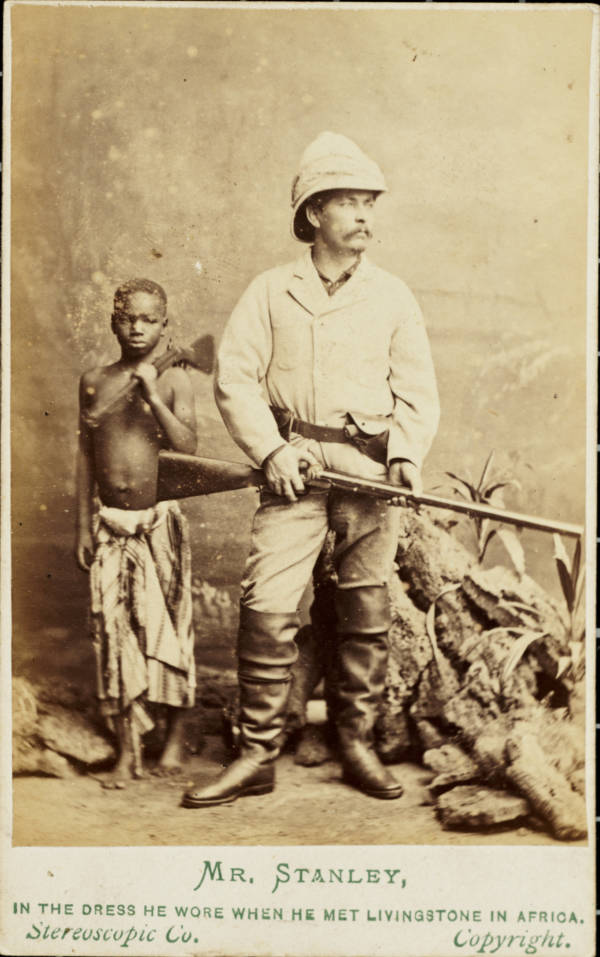

Across an ocean, another man had taken on a quest of his own. Henry Morton Stanley, a reporter for the New York Herald, had been tasked by his editors with either finding the British explorer, who by this point had the international reputation of a modern superstar, or to “bring back all possible proofs of his being dead.”

Wikimedia CommonsJournalist Henry Morgan Stanley had an adventure of his own in pursuit of Livingstone.

Stanley set out from Zanzibar in March of 1871 by which point Livingstone had been missing for nearly seven years.

In an impressive journey on its own, over the next seven months, Stanley also battled illness and desertion by his group. Like his quarry, however, Stanley was determined to see through his mission, declaring “wherever [David Livingstone] is, be sure I shall not give up the chase. If alive you shall hear what he has to say. If dead I will find him and bring his bones to you.”

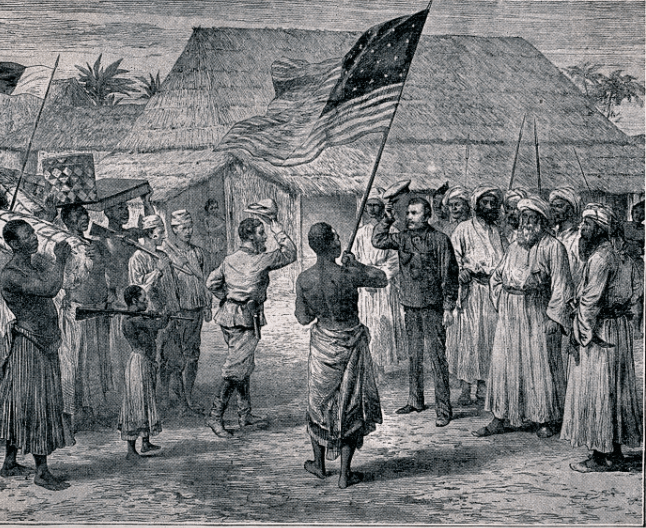

By 1871 Livingstone had traveled farther west into Africa than any European had in recorded history. But he was, by his own admission, “reduced to a skeleton” and gravely ill from dysentery. When he reached the town of Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika in October 1871, he was wasting away and beginning to lose hope. Then, a month later, just when things seemed to be most dire, a remarkable incident occurred. One day on the streets of Ujiji, he caught sight of an American flag fluttering above the caravan of some “luxurious traveler…and not one at wit’s end like me.”

To the explorer’s surprise, the stranger from the caravan strode right up to him, extended his hand, and as if they were being introduced at a London theater rather a remote village in the farthest reaches of Africa, politely inquired, “Dr. Livingstone I presume?”

David Livingstone’s Legacy And Death

Stanley had brought David Livingstone the supplies he so desperately needed, the Scotsman himself declared “You have brought me new life.” When the reporter returned home and published his account of the encounter and the single phrase which has perhaps become more famous than the doctor himself, he cemented the explorer’s legacy.

Although Stanley begged Livingstone to return with him, Livingstone refused. Two years later, in May of 1873, he was found dead in Northern Zambia still in pursuit of his quest to find the Nile’s source. His heart was removed and buried in African soil. His body was returned to England where it was interred in Westminster Abbey in 1874.

The meeting of Livingstone and Stanley was immortalized after the journalist recounted his famous phrase “Dr. Livingstone I presume.”

Although David Livingstone was a huge celebrity in his time and once considered a national hero, his legacy today is a bit more complicated. As remarkable as his discoveries were, his accounts of his adventures in Africa stirred interest in the continent and triggered the “scramble for Africa.”

Although this was hardly Livingstone’s intent and he died before the worst of it had even begun, the colonization of Africa by various European powers had devastating consequences for the inhabitants which are still played out today.

After this look at David Livingstone,, read about the unfortunate consequences of Livingstone’s explorations with the story of the genocide in East Africa and Belgium’s colonial King Leopold.