From the original Penn Station to the Old Cincinnati Library, these majestic landmarks were demolished to make room for parking garages, offices, and more "modernized" buildings.

Urban development is a vital part of any society. As populations grow, cities must be able to provide their residents with government services, infrastructure, and entertainment facilities. Unfortunately, this often leads to destroyed landmarks and demolished historic buildings.

As the population of the United States boomed after World War II, society had to change rapidly to keep up. Urban centers spread, leading to the rise of suburbia. And with that expansion came the need for more transportation.

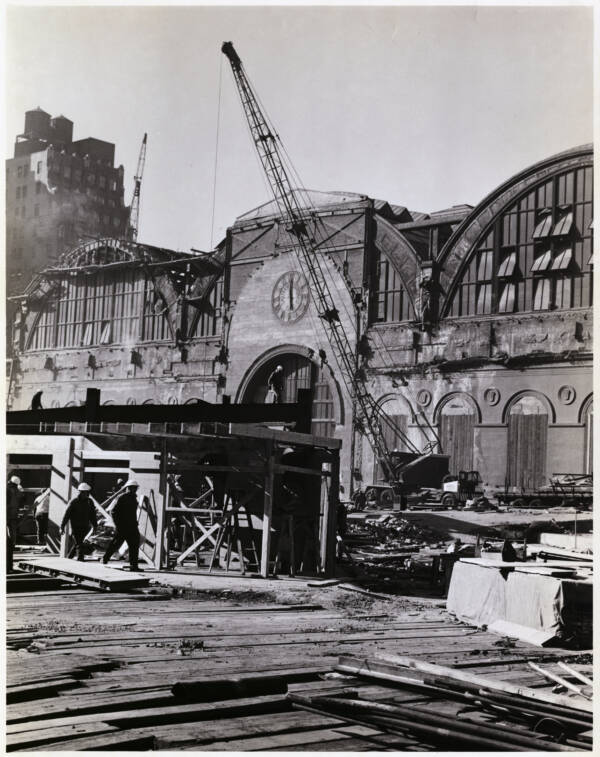

George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty ImagesThe demolition of the original Penn Station in New York City. Circa 1963.

Some cities established effective systems of public transportation, but others relied heavily on car travel. The healthy economy allowed the average family to afford a personal vehicle, and the funding of the Interstate Highway System in 1956 only added to the need for cars and places to park them.

However, to make way for all the new roads, parking garages, and transportation systems, older structures had to come down. And around the same time, many elaborate homes and businesses of yore were razed in order to appease America’s love affair with modern skyscrapers.

Here are 11 landmarks that were destroyed in the name of development.

The Original Penn Station, New York City

When it comes to destroyed landmarks, New York's Pennsylvania Station — better known as Penn Station — is often one of the first to come to mind. Today, it sits beneath Madison Square Garden in Midtown Manhattan and serves more than 600,000 daily passengers, according to The New York Times. But before it was pushed underground in the 1960s, Penn Station was a "beautiful Beaux-Arts fortress" that was one of the city's crown jewels.

With 84 giant Doric columns, 22 eagle sculptures, and a 138-foot-high ceiling, the building was an architectural marvel. By the 1950s, however, passenger volume had declined, and the building had become expensive to maintain — so the Pennsylvania Railroad decided to demolish the head house and train shed while keeping the underground tracks in service.

In 1961, plans to construct the Madison Square Garden sports and entertainment complex atop Penn Station were announced, but the scheme soon faced public controversy. The famed art historian Vincent Scully once wrote of the sharp contrast between the old structure and the new one: "One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat."

Despite public resistance, however, demolition of the original Penn Station began in October 1963, and Madison Square Garden opened five years later.

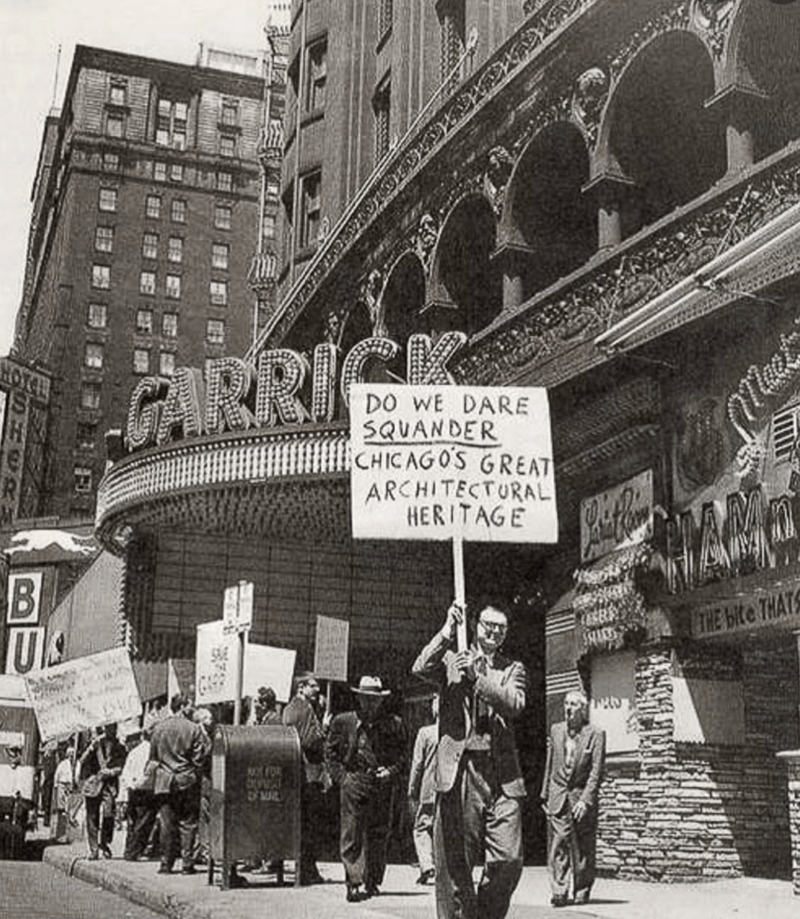

Garrick Theater, Chicago

In the late 19th century, architects Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler collaborated to design the Schiller Building in Chicago. At the time of its construction, it was one of the tallest structures in the Windy City.

Opened in 1891, it was initially intended for the German Opera Company as a place to hold musical and cultural events. But the building soon changed hands. It became known as Garrick Theater and began hosting stage shows.

Over the course of its short life, the building also housed a movie theater and a television studio. However, after a decline in business, the 1,300-seat theater was razed in 1961, and a parking garage was built on the site.

According to the Chicago Reader, there was such an uproar against the demolition that it sparked Chicago's historic preservation movement and contributed to the passing of the city's Landmark Ordinance of 1968.

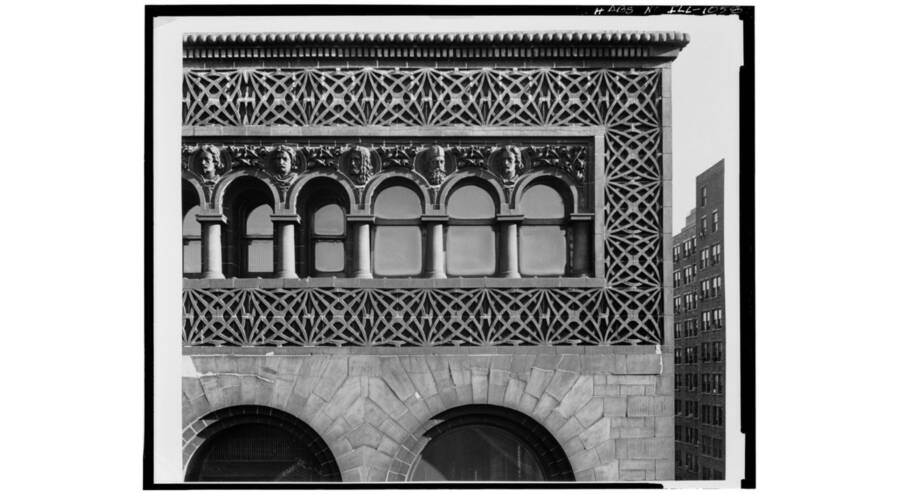

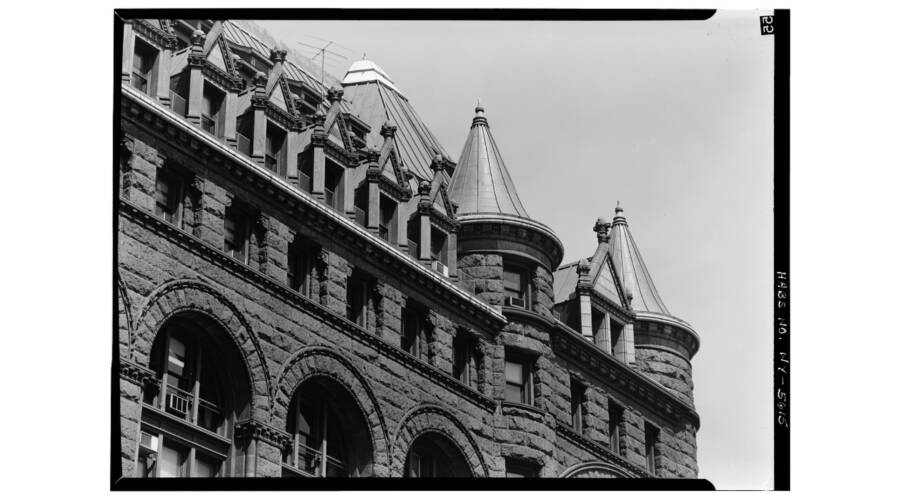

Erie County Savings Bank, Buffalo

In 1890, construction started on the eye-catching new headquarters for the Erie County Savings Bank in Buffalo, New York. The Romanesque Revival building was designed by architect George B. Post and boasted 10 stories of stunning red granite, according to Western New York Heritage Press.

Thomas Edison himself designed the building's electrical system, and the bank was officially opened in 1893. Sadly, the structure stood for about 75 years before it was demolished in 1968 as part of an urban renewal project.

Architect Harold L. Olmsted, who tried to help save the building, said: "The whole place, upstairs and down, reeks with honesty and open-minded intelligence from its delightful pavement blocks to its heavily paneled doors and wainscots, its lovely windows and the views they so adequately and amusingly frame... its charming variance in plan from the usual."

Still, the triangular, castle-like structure was ultimately replaced by a skyscraper called Main Place Tower, which served as the bank's new headquarters until the business was dissolved in the 1990s.

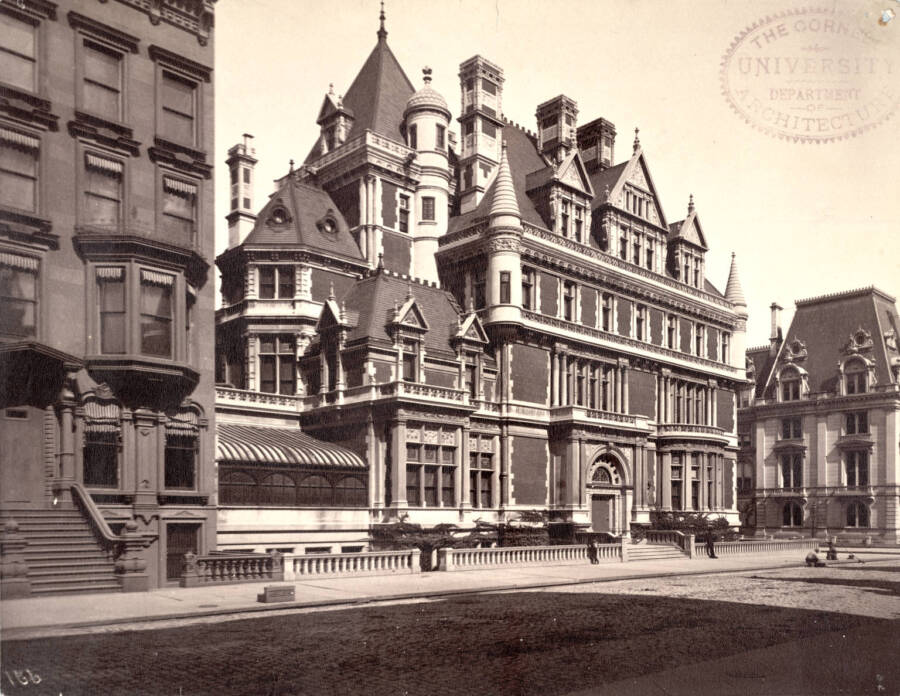

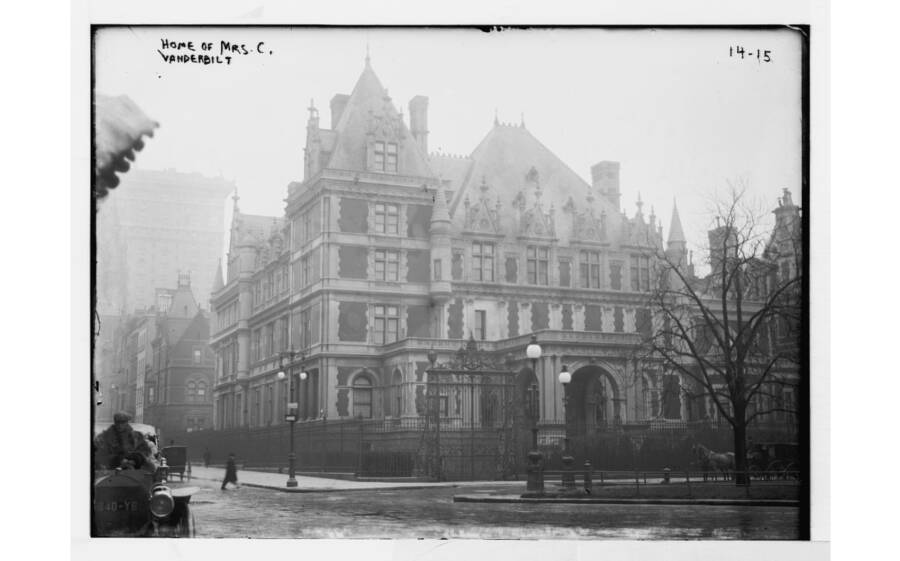

Cornelius Vanderbilt II House, New York City

Even in the 19th century, Fifth Avenue was one of the wealthiest streets in New York City. According to Untapped Cities, Cornelius Vanderbilt II — the favorite grandson of the successful American railroad magnate — decided to build his own luxurious house on "Millionaire's Row" in 1883.

Vanderbilt hired famed architect George B. Post to design a five-story home that he later expanded into a 130-room mansion. It was reportedly the largest single-family home in the city, and Vanderbilt made sure to leave his wife a large trust fund so that she could maintain it after his death in 1899.

However, in 1926, Alice Vanderbilt was forced to sell the home due to extensive commercial development nearby. Developers paid $7 million for the mansion — and then promptly tore it down to build Bergdorf Goodman, the luxury department store that remains on the site to this day.

That said, some bits and pieces of Vanderbilt's house are still scattered around the city, from the front gates that stand in Central Park to the fireplace that can now be seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

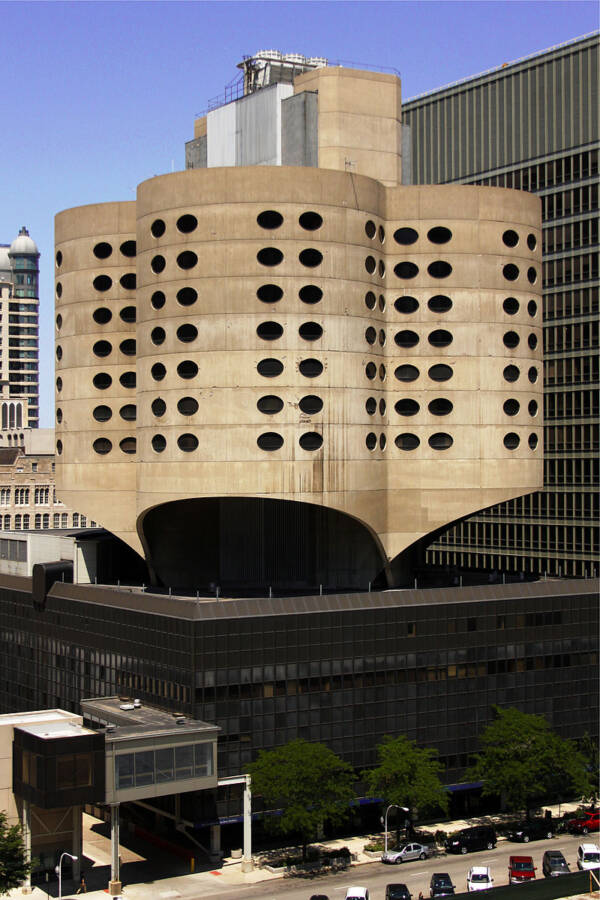

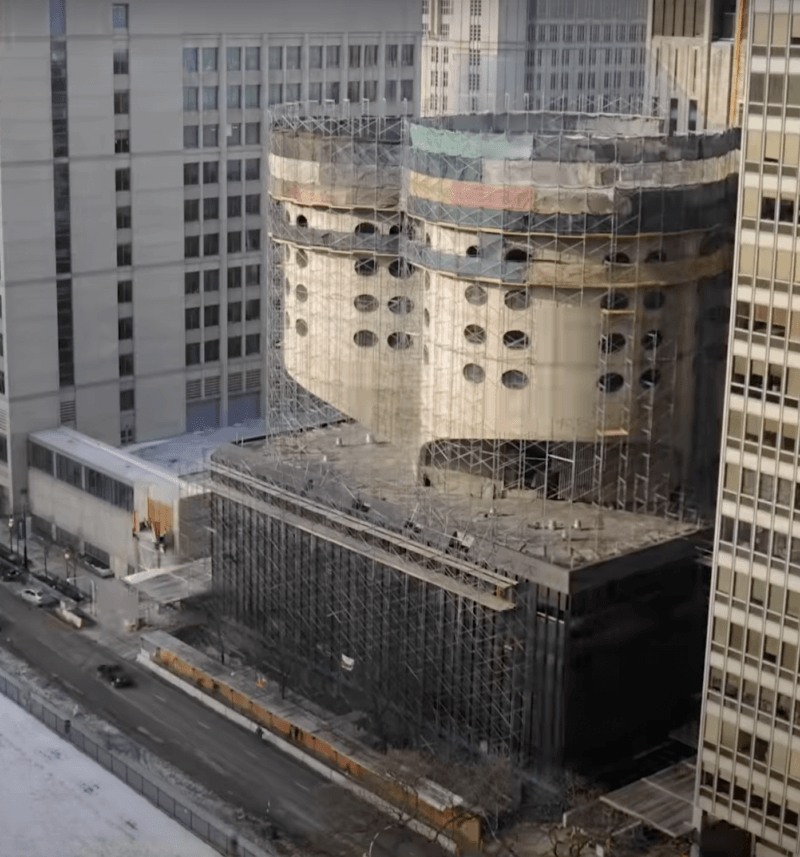

Old Prentice Women's Hospital, Chicago

Most destroyed landmarks are from times long past, but it's just as devastating when newer works of art are demolished. In 1975, an exceptionally unique hospital opened in Chicago, Illinois. Designed by architect Bertrand Goldberg, the old Prentice Women's Hospital featured a nine-story quatrefoil tower placed atop a five-story rectangular building.

The Brutalist style and distinctive shape made the hospital "the only example of its type anywhere in the world," according to structural engineer William F. Baker. Interestingly enough, it was also one of the first construction projects to be designed with the help of computer software.

But when a more modern hospital was built in 2007, the old Prentice Women's Hospital was no longer needed. The building was vacated in 2011, and Northwestern University soon announced its plans to demolish it and build a state-of-the-art research center in its place. The idea faced intense backlash, and preservationists began petitioning the Chicago Landmarks Commission to save the structure, according to DNAinfo Chicago.

However, after years of debate, Northwestern received permission to raze the building, and the demolition was completed in 2014. Today, the 14-story Simpson Querrey Biomedical Research Center towers over the site.

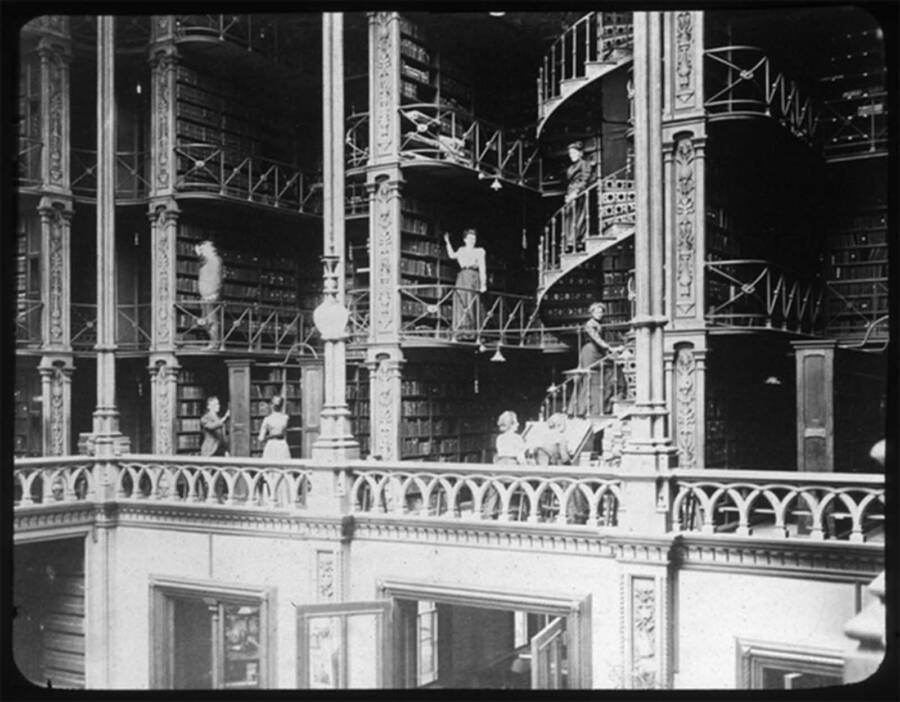

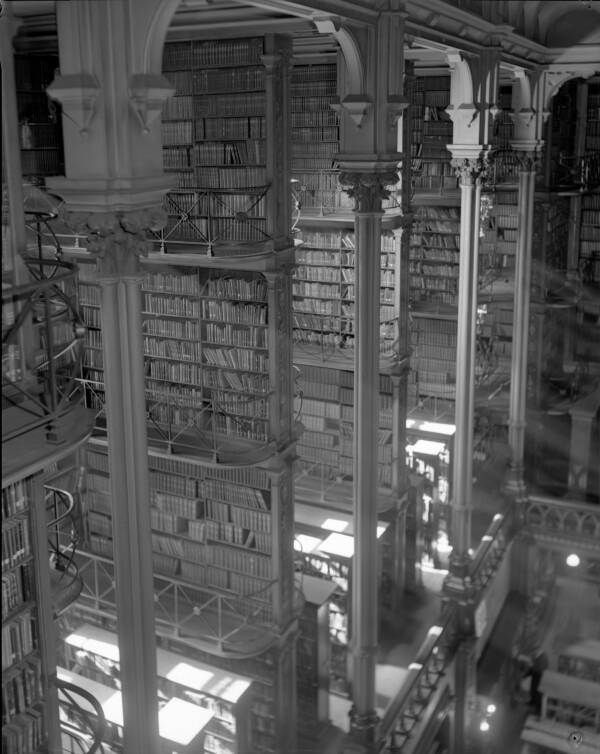

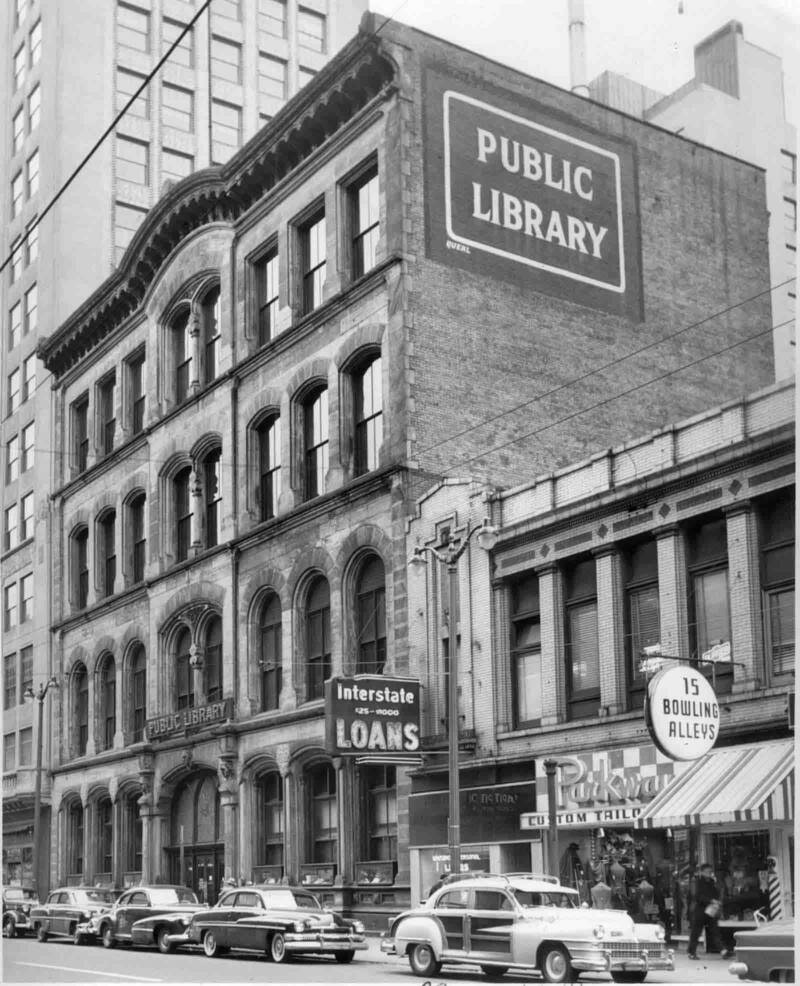

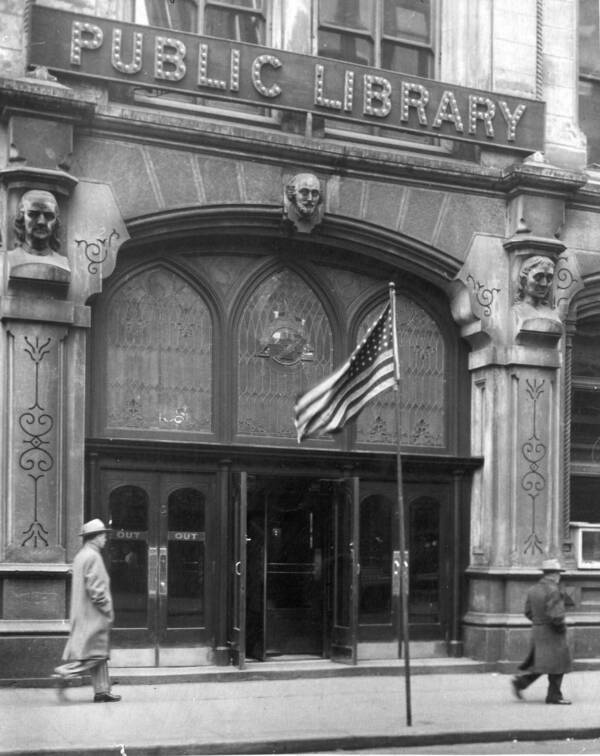

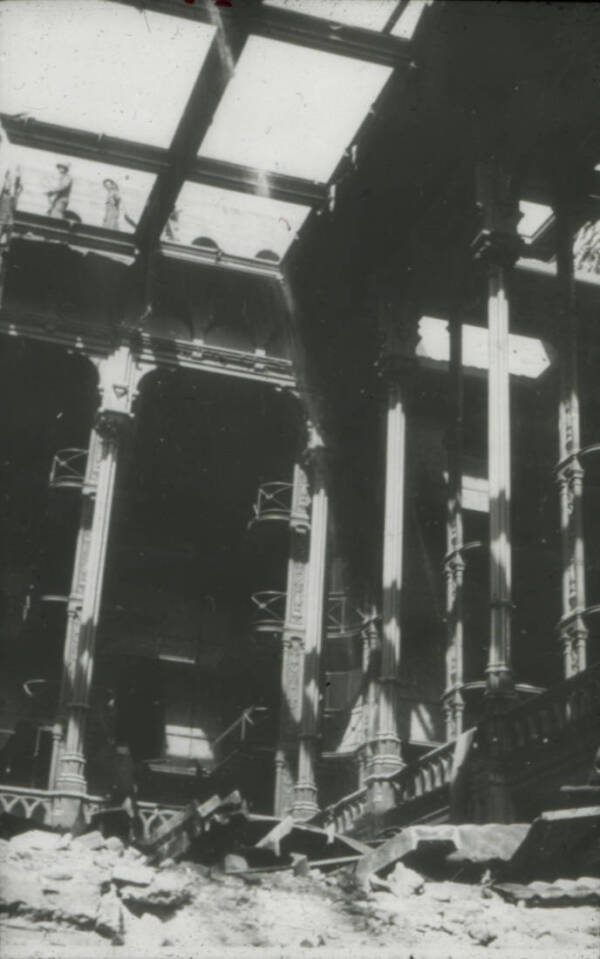

Old Cincinnati Library, Cincinnati

For about 80 years, the Old Cincinnati Library looked like something out of a movie. With marble floors, towering bookshelves, spiral staircases, and skylights, the building on Vine Street housed one of the most beautiful libraries in the world. The "Old Main" Library opened in 1874, and the interior — which was designed by J.W. McLaughlin — immediately stunned patrons.

The building was initially intended to be an opera house, but it was transformed into a public library after the original project lost funding. During the library's opening, the Cincinnati Enquirer praised the unique structure: "One is impressed not only with the magnitude and beauty of the interior but with its adaptation to the purpose it is to serve."

However, by the 1920s, the library was running out of room for all its books. And in 1955, a new library opened just down the road. The gorgeous building was soon demolished, and today a parking garage sits on the site.

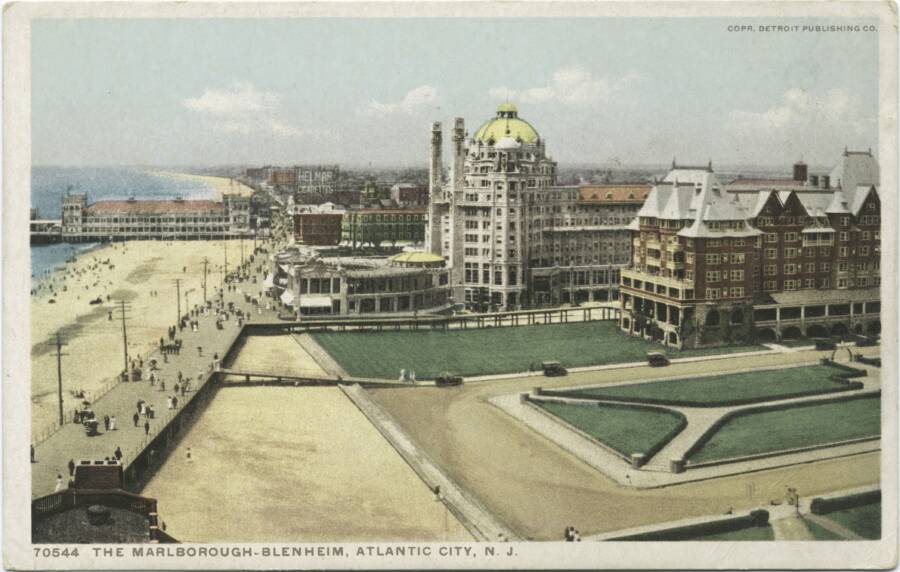

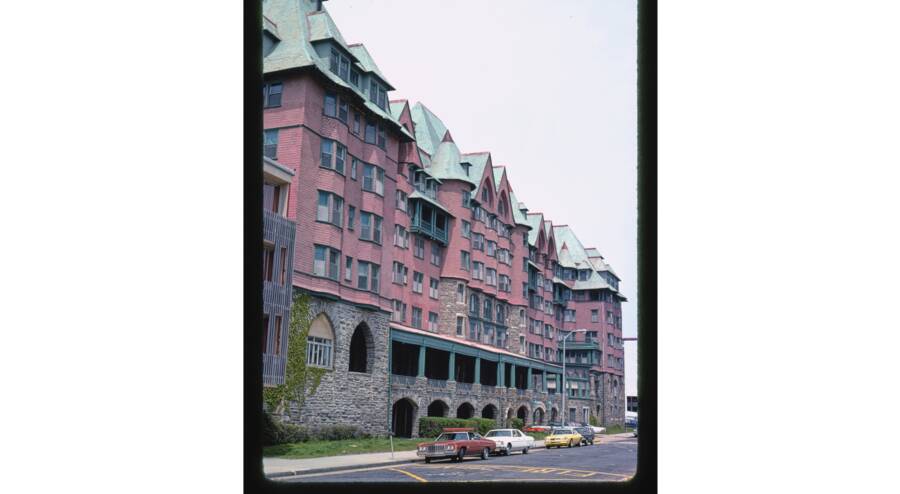

Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel, Atlantic City

In 1902, Josiah White III began building a Queen Anne-style hotel in Atlantic City, New Jersey, which he dubbed the Marlborough. Shortly thereafter, he decided to expand the resort and hired architect Will Price to help him design a separate tower called the Blenheim, which was named after Winston Churchill's birthplace and ancestral home in England.

It was the largest reinforced concrete building in the world at the time, and it featured Spanish and Moorish themes and a towering dome. Together, the two buildings formed the Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel. It became a staple of Atlantic City, and Winston Churchill himself even stayed there in 1916.

But then in 1977, Bally Manufacturing, a large producer of slot machines, took control of the property, according to the Atlantic City Experience. Despite fierce protests, the company demolished the hotel and built Bally's Park Place Casino and Hotel on the site of the destroyed landmark.

Today, Bally's Atlantic City is one of the largest hotels on the boardwalk, boasting 83,000 square feet of gaming space with over 1,300 slot machines.

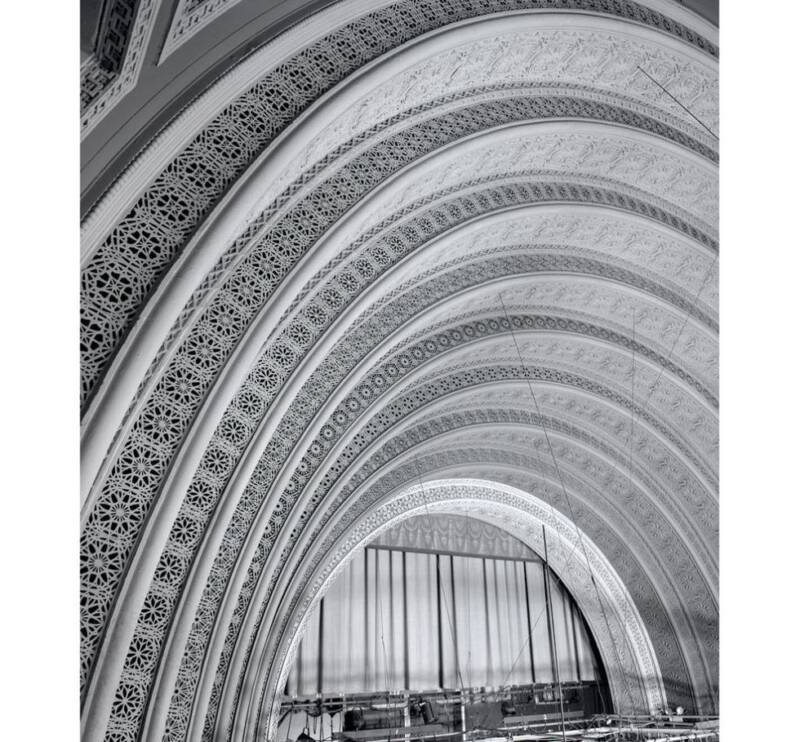

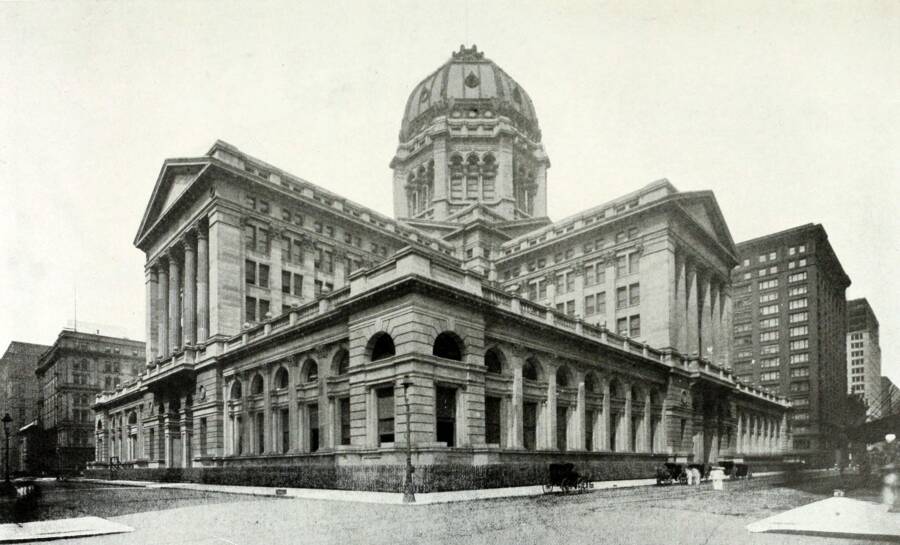

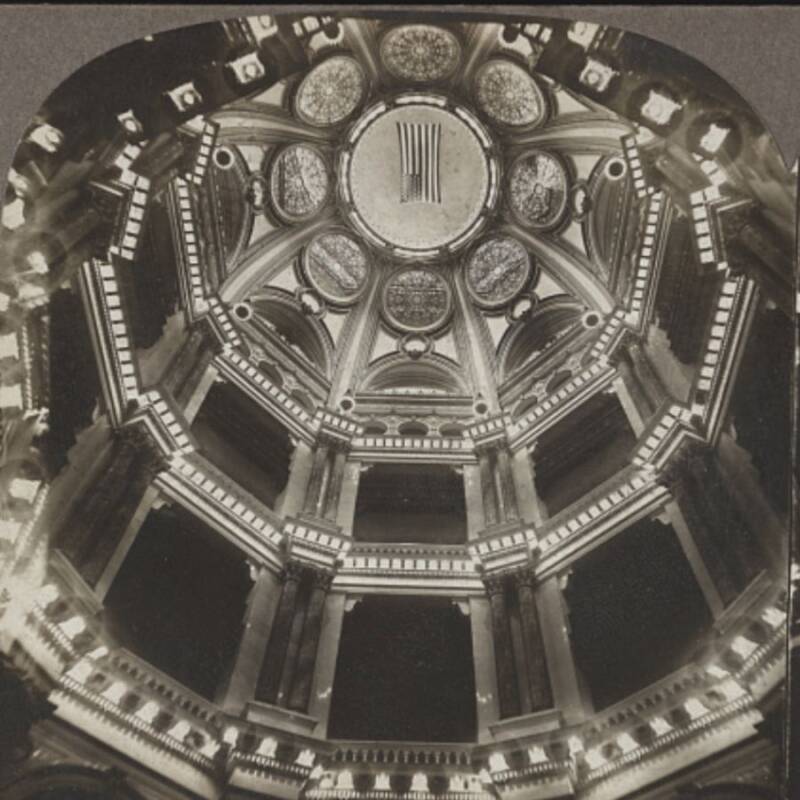

Chicago Federal Building, Chicago

In the late 19th century, Chicago's population started to grow rapidly, especially after the city hosted the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. The courts, post offices, and other government bureaus were having trouble handling the massive influx of new citizens, so the city constructed the Chicago Federal Building to better serve the expanding community.

According to Preservation Chicago, architect Henry Ives Cobb designed the Beaux-Arts structure, which featured a two-story base topped with a six-story Greek cross. It also boasted a 300-foot-high octagonal rotunda.

For about 60 years, this building housed several federal agencies. It also held decades of Chicago history within its walls. The trial of notorious gangster Al Capone for tax evasion was held in one of the building's courtrooms, and Walt Disney had once worked at the post office inside the same building.

But in 1965, the Chicago Federal Building was demolished, and the destroyed landmark was replaced by the Kluczynski Federal Building, a 45-floor structure made of steel and glass that still stands there today.

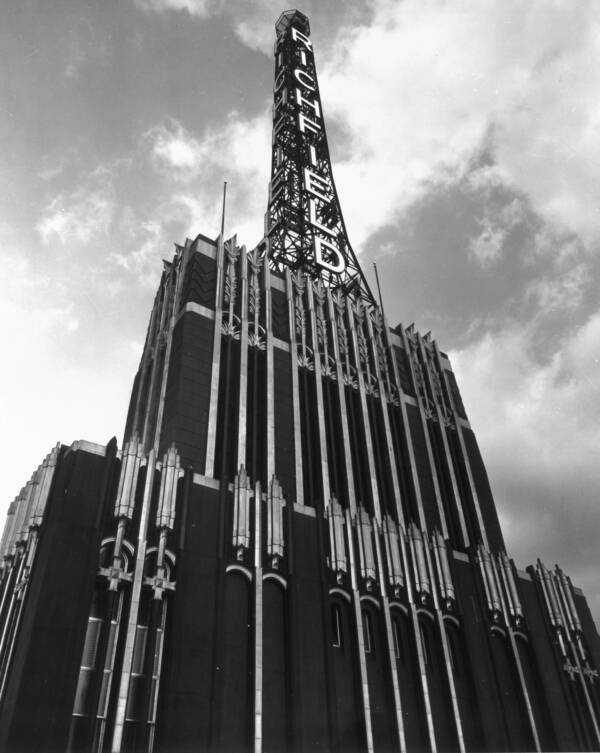

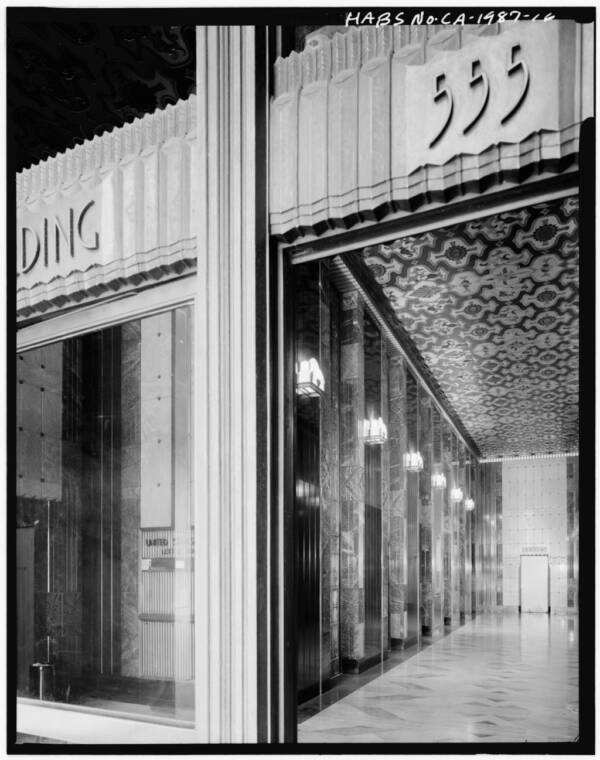

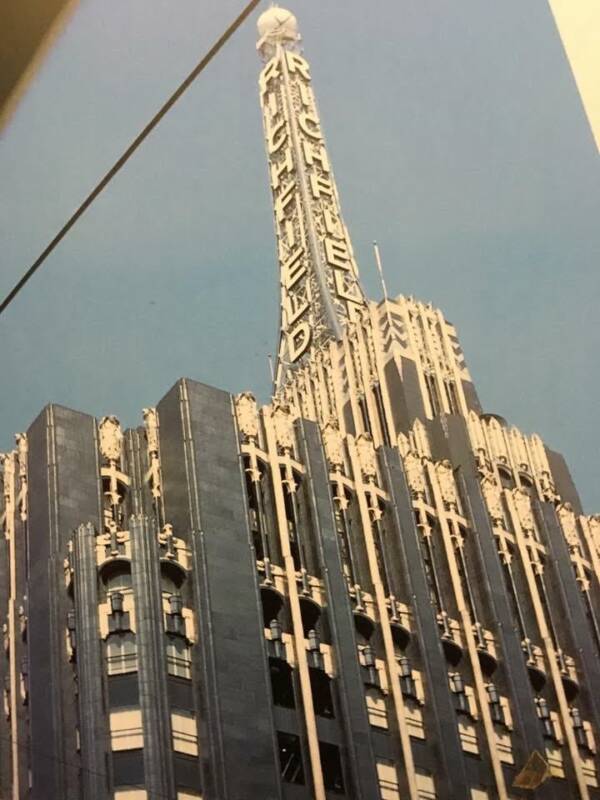

Richfield Tower, Los Angeles

Also known as the Richfield Oil Company Building, the Richfield Tower in Los Angeles was built between 1928 and 1929. Designed by Stiles O. Clements, the building boasted a striking black and gold Art Deco facade. This helped it stand out amongst all of the other structures that surrounded it.

According to the Pacific Coast Architecture Database, the unique style choice was meant to symbolize "black gold," the nickname for oil due to its dark color and high value. Likewise, the lighting on the 130-foot beacon at the top of the building was meant to simulate an oil derrick.

The structure stood 372 feet high, including the beacon, which was emblazoned with the word "Richfield." By the 1960s, however, the Richfield Oil Company had outgrown the building. It was demolished in 1969, and the ARCO Plaza skyscraper complex — now known as City National Plaza — was built on the site. However, the remarkable elevator doors from the destroyed landmark were salvaged and reused as decor on the plaza.

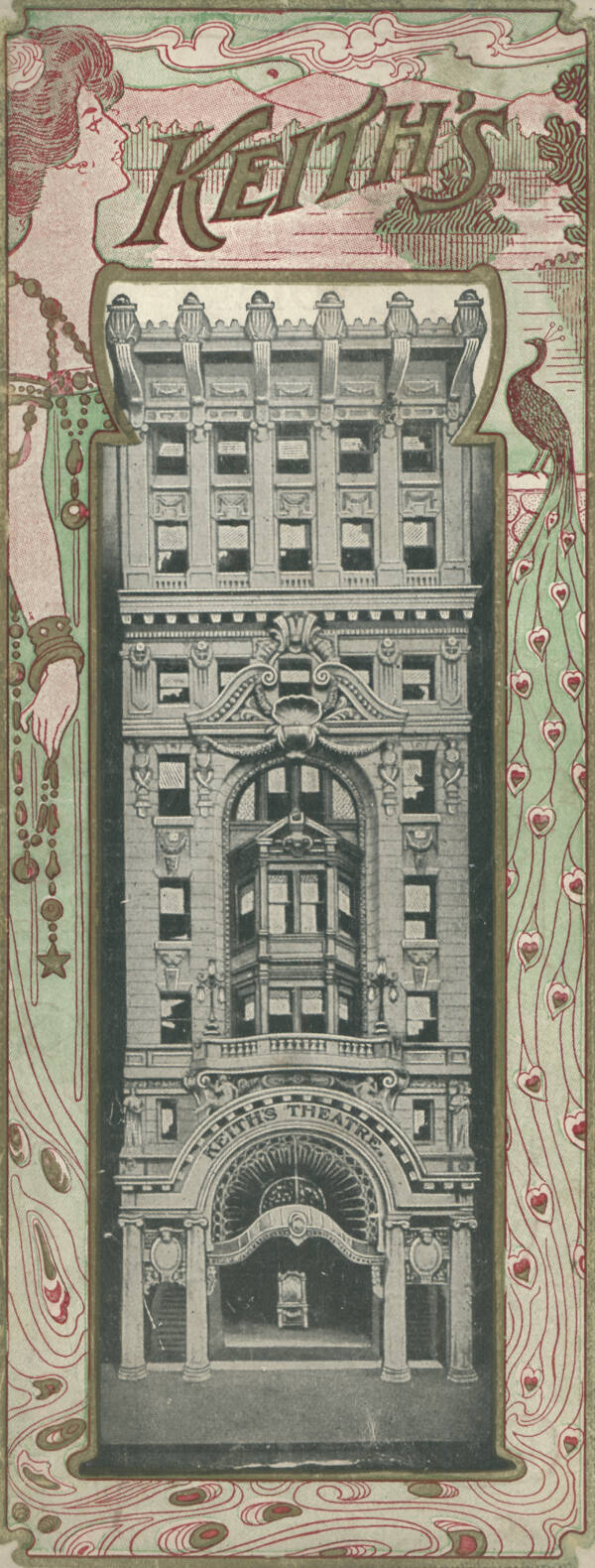

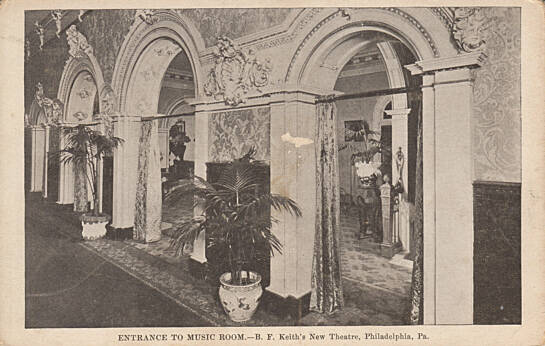

Keith's New Theatre, Philadelphia

In 1901, impresario Benjamin F. Keith opened Chestnut Street Keith's Theatre — later known as Keith's New Theatre or simply Keith's Theatre — in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The stunning building, which hosted vaudeville shows, featured a recessed entrance, a triumphal arch, and Ionic columns.

Keith's New Theatre became a major destination for stars like Charlie Chaplin and the Marx Brothers. However, as vaudeville entertainment became less popular, the theater lost business. According to the Free Library of Philadelphia, William Goldman purchased the building in 1943, turned it into a movie theater, and renamed it the Randolph Theatre after his late son.

In 1971, the theater was closed, and the once-impressive building was demolished. Today, the site is home to various retail and office buildings.

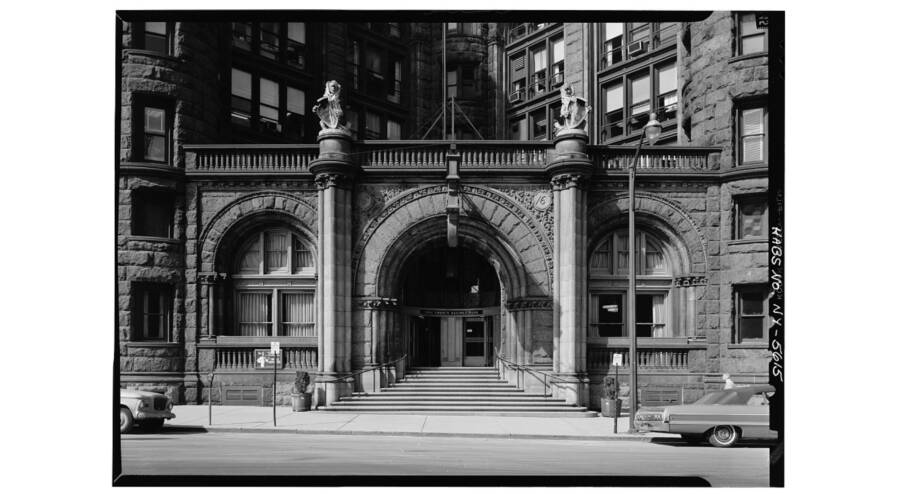

Imperial Hotel, Indianapolis

In the 1850s, Dr. Horace R. Allen founded the National Surgical Institute, and the hospital quickly expanded, establishing satellite services in multiple cities. By the 1890s, he had built a four-story structure in Indianapolis, Indiana, with the intention of housing the institute there. But high construction costs quickly caused the institute to go bankrupt.

The striking Queen Anne/Romanesque Revival building that briefly held the hospital soon became the Imperial Hotel. Since it was so close to the Indiana State House, the hotel housed many legislators in its 200 rooms. According to Historic Indianapolis, it also held Turkish baths and a saloon.

The Imperial Hotel closed in 1914. Then, the Hotel Metropole took over for several years, at one point hosting soldiers who were attending classes nearby in its "barracks." When Hotel Roosevelt took control of the building in the 1920s, the new owners removed the domes, balconies, and roof decorations, perhaps in an attempt to modernize the structure.

However, in the late 1940s, the entire building was demolished to make way for an expansive parking lot. Today, many people who park there likely have no idea that a stunning hotel once stood in the same spot.

After looking through these photos of 11 destroyed landmarks, learn about the nine oldest structures in the world that are still standing today. Then, check out these pictures of old New York before the skyscrapers.