As the face of the economic reunification of Germany, Detlev Rohwedder was a major target to the thousands of East Germans who lost their jobs after the collapse of communism.

As one of the faces of Germany’s reunification process, Detlev Rohwedder was also one of the country’s most heavily targeted people. A successful German politician and businessman, Rohwedder was responsible for privatizing the socialist East German businesses as the country reformed.

For the millions who had suffered because of the split between the East German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of West Germany at the end of World War II, Germany’s reunification on Oct. 3, 1990 — 45 years later — heralded a promising future.

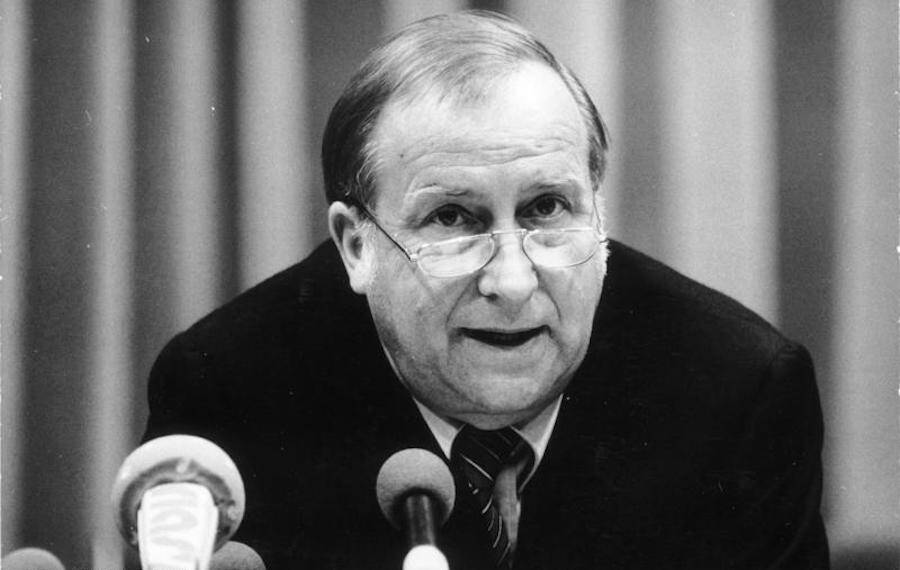

Wikimedia CommonsDetlev Rohwedder was killed by a sniper positioned 200 feet away from his bedroom window.

But not everyone was content with the government’s demands to make this so — least of all the Red Army Faction (RAF). This leftist militant group believed that Rohwedder’s department was overreaching by absorbing East German businesses into the newly unified nation.

Perhaps it was no surprise, then, when Rohwedder was found murdered by sniper fire, shot through his bedroom window while still in his pajamas in 1991. His assassination remains one of the most infamous political hits in modern German history.

The Netflix documentary A Perfect Crime aims to explore the still-unsolved case of Rohwedder’s murder. But before watching, debrief on his short but controversial career.

Detlev Rohwedder’s Role In Reunifying Germany

Born Detlev Karsten Rohwedder on Oct. 16, 1932, in Gotha, Germany, Rohwedder came of age during Nazi Germany’s last gasps. He was in his early teens when World War II and the reign of the Third Reich ended.

Consequently, Germany was divided between the Allied powers. Great Britain took northwest Germany, France took the southwest, the United States the south, and the Soviet Union took the east. It was in this split nation that Rohwedder grew up.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Berlin Wall and East Germany’s Neue Zeit newspaper offices in 1984.

But life in divided Germany was difficult. Millions of families, friends, and countrymen were divided by a literal wall. Any attempts to flee from one side to the other could result in death. Those living in the east where subjected to food scarcity, constant surveillance, and a general lack of civil liberties.

The Allied powers had stipulated in the so-called Potsdam Agreement of 1945, which set the terms for how a divided Germany would be governed, that “when a government adequate for the purpose” arrives, the Government of Germany could unify and make peace. This government seemed to arrive in the late 1980s with the beginning of Die Wende, or Germany’s Peaceful Revolution.

At the same time, the Soviet Union, and consequently East Germany’s Communist Party, began to collapse. Die Wende saw an end to the Soviet government in East Germany and marked its transition into a parliamentary democracy. As such, reunifying East and West Germany actually seemed possible at this stage.

And so, Germany’s 45-year period of division ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall in late 1989.

It was shortly after this that East German officials, the Soviet Union, West German officials, and Allied powers including France, the United Kingdom, and the United States initiated talks of reunification. As it just so happened, Detlev Rohwedder would play a pivotal part in this.

In 1990, the government of East Germany created the Treuhandanstalt, or the Treuhand trust, to take control of previously state-owned East German companies that would then be integrated into the new unified nation. Rohwedder was appointed to the helm of Treuhand as its first — and short-lived — president.

At the time, Treuhand was the world’s largest holding company and was tasked with restructuring and selling anywhere between 8,500 and 12,000 East German-owned companies.

As a result, Treuhand was responsible for the fates of over four million East German employees. Treuhand oversaw enterprises from steel works to Germany’s film production headquarters, Babelsberg Studios, and it took control of 2.4 million hectares of agricultural land and forests, including the properties that once belonged to the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police.

Klaus Rose/Ullstein Bild/Getty ImagesDetlev Rohwedder watches as employees of steel works Hoesch AG protest the restructuring of their company.

But the merger of these companies did not go as planned. As it turned out, the East German economy was worth four times less than West Germany’s. Treuhand racked up nearly 300 billion in debts and struggled to sell off as many East German businesses as it could.

As a result, upwards of 20 percent of East Germany was left unemployed. Strikes broke out in mines and steel works across East Germany as they dissolved.

And as president of Treuhand, Rohwedder became a major target for the frustration of East German workers.

Assassinated In His Home

Hartmut Reeh/Picture Alliance/Getty ImagesThe three bullet holes in Detlev Rohwedder’s bedroom window.

It was the night of Easter Monday in 1991. Only six months had passed since Germany merged, but Rohwedder regularly received death threats for how Treuhand had treated East German businesses. As such, the police established an intermittent security presence at his lavish West German residence situated in the quiet Niederkassel suburbs of Düsseldorf.

Rohwedder lived with his wife, Hergard, who had just days before his assassination pleaded desperately for increased security at their home. Authorities had only bulletproofed the ground floor windows, leaving the rest of the house vulnerable to attack. What’s more, the authorities allegedly patrolled the area rather leisurely.

Perhaps that is how, at around 11:30 p.m. that night, Detlev Rohwedder was shot through his bedroom window, dressed in his beige-blue pajamas.

Rohwedder had been sitting at his desk and was presumably shuffling toward his closet when the first shot struck him. It did irrevocable damage, and tore through his carotid artery, trachea, and esophagus. Hergard heard the crashing glass and rushed into the room, only to be shot in the left elbow.

Hartmut Reeh/Picture Alliance/Getty ImagesThe 58-year-old’s body is taken in for an autopsy.

A third shot redecorated Rohwedder’s bookshelf, but the Treuhand president was already dead due to blood loss. His shocked wife called police immediately, who then set up a large-scale search for the shooter within three minutes — but to no avail.

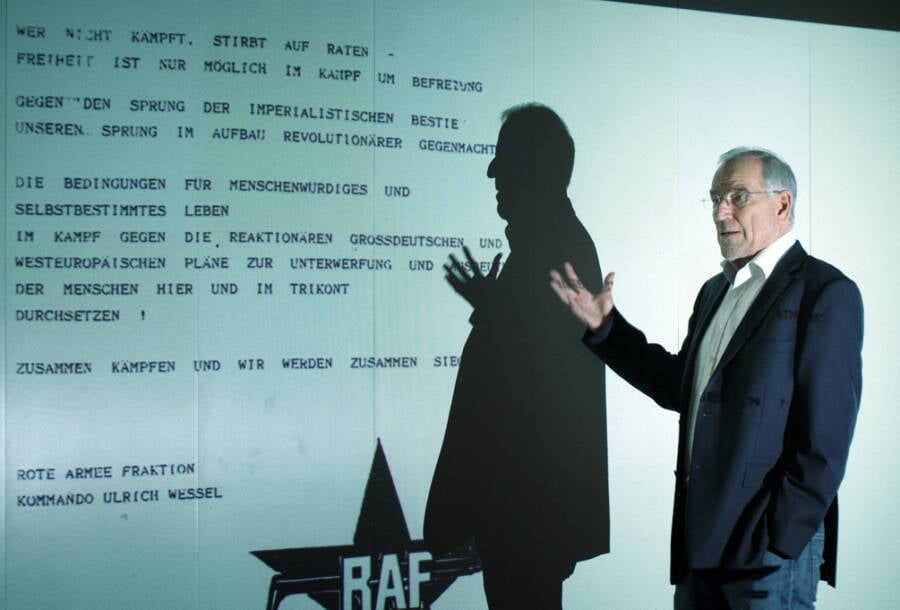

What the authorities did find, however, was a letter of confession signed by a RAF commando named “Ulrich Wessel.” Authorities believed it to be a genuine RAF document as it was stamped with the organization’s five-pointed star. It was discovered 200 feet from Rohwedder’s house along with three cartridge cases, a plastic chair, and a towel containing a strand of hair.

Hartmut Reeh/Picture Alliance/Getty ImagesInvestigators secure the plastic chair found alongside the letter outside Detlev Rohwedder’s home.

In 2001, DNA testing matched the hair on the towel found outside Rohwedder’s home to Wolfgang Grams, a RAF member who was already been dead for eight years. He had been killed while exchanging gunfire with Germany’s GSG-9 anti-terrorism unit in Bad Kleinen.

The murder weapon, which was a 7.62x51mm NATO standard caliber rifle, was found to be the same rifle used during a RAF sniper attack on the American embassy earlier that year. It seemed obvious that Rohwedder’s murder was orchestrated by the militant leftist group, but questions lingered.

Investigating The Murder Of Detlev Rohwedder

The militant group was founded by students Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof in the 1960s. It quickly escalated from a 1960s antiwar group to a 1970s guerrilla organization that targeted politicians and West German businessmen. They claimed to have killed as many as 34 people and injured over 200.

Bundeskriminalamt (Federal Criminal Police Office)The towel containing the strand of hair matching Wolfgang Grams’ DNA in 2001.

Rohwedder embodied the group’s core misgivings. Not only had he presumably made enemies as federal minister of finance in Germany’s then-capital of Bonn during the 1970s, but he had incorporated, restructured, and sold assets formerly belonging to East Germany’s secret police in 1990.

Furthermore, it was discovered that RAF had formed a close relationship with the Stasi that continued well into the late 1990s. Whoever was responsible, the authorities concluded that they were clearly a professional who had been observing the movements of Rohwedder for some time.

NetflixNetflix’s A Perfect Crime aims to detangle the complex web of motives and parties involved in Detlev Rohwedder’s murder.

Treuhand ultimately dissolved shortly after Rohwedder’s death, which itself was never officially solved.

In 2007, however, former RAF member Eva Haule publicly claimed that the group was indeed responsible. “If this weren’t the case, there would have been immediate correction on the matter,” she said. “Even if just for political transparency.”

The Netflix documentary A Perfect Crime will aim to untangle the web of motives and shadowy intelligence ploys that culminated in Detlev Rohwedder’s murder. But in the end, a straight answer might never arise.

After learning about the political assassination of German politician Detlev Rohwedder, read about the history of the Berlin Wall. Then, learn more about life in East Germany through these 33 revealing photos.