Researchers think the shark developed its rotating jaw to accommodate tooth regrowth.

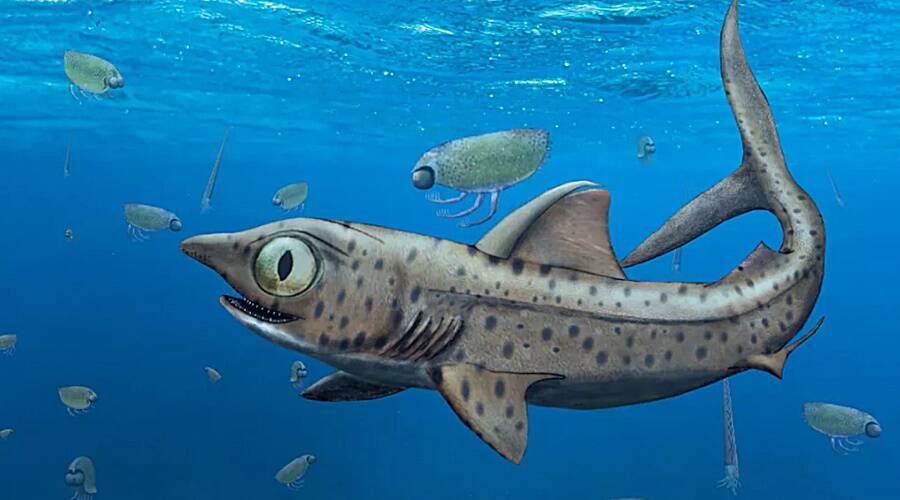

Christian Klug/UZHFerromirum oukherbouchidates lived on Earth 370 million years ago.

Scientists have uncovered the remains of a prehistoric shark that once lurked in the waters of what is now Morocco. A new study on the shark fossils suggests that it possessed the terrifying ability to rotate its jaw, where a hidden row of sharp teeth jutted outward when its mouth opened to feed.

According to Live Science, this prehistoric shark called Ferromirum oukherbouchidates lived 370 million years ago. It was a ferocious predator of the ocean with an agile, slender body measuring about 13 inches long. It had a short triangular snout with unusually large eyes, with orbits taking up about 30 percent of its braincase’s total length.

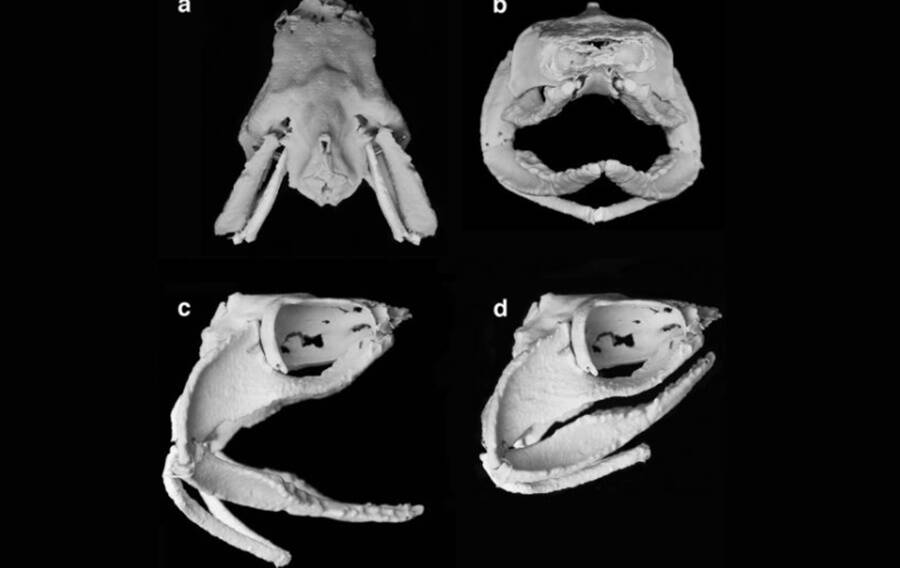

In a study published in the journal Communications Biology, researchers examined the skull and jaw of the prehistoric shark using computed X-ray tomography (CT), then created a 3D model to conduct physical tests. They found some interesting things from their study.

Frey et alScientists used advanced CT scanning to recreate a 3D model of the shark’s distinct jaw.

The biggest difference researchers found between the F. oukherbouchidates and their modern-day brethren was their unique dental structure. Modern sharks easily lose any tooth worn down by their mighty bite and quickly grow a new tooth in its place.

But the prehistoric shark’s jaws were completely different. Whenever the prehistoric shark lost one of its teeth, a new tooth sprouted in a row on the inside of the jaw, next to the older teeth. Their new tooth didn’t grow upward but curved inward toward the shark’s tongue, essentially flattening its row of teeth when its mouth was closed.

When the prehistoric shark opened its mouth, the cartilage at the back of the jaw would flex so that the sides of the jaw “folded” down and the newer, sharper teeth rotated upward. This enabled the prehistoric shark to launch a remarkably lethal bite into its prey using as many teeth as possible.

When the shark’s jaw closed again, the force of its jaw would push seawater and its prey down toward the throat while, at the same time, its sharp new teeth rotated inward to trap its prey. This horrifying feeding method is known as suction-feeding.

“Through this rotation, the younger, larger, and sharper teeth, which usually pointed toward the inside of the mouth, were brought into an upright position. This made it easier for animals to impale their prey,” said Linda Frey, lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate with the Institut für Paläontologie und Paläontologisches Museum at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

PixabayThe F. oukherbouchi was unable to quickly regrow lost teeth like modern sharks do.

The remarkable jaw pattern movement, scientists wrote, was unlike anything ever found in any living fish to date.

One living shark species that has a similarly shocking jaw function is the goblin shark, which can expand and retract its jaw to lunge at unsuspecting prey. But the goblin shark’s quirky ability would still be no match for the ferocious feeding behavior of the F. oukherbouchidates.

This rotating jaw disappeared as modern shark species evolved, equipped with speedy tooth regrowth.

The discovery has given researchers a key opportunity to further understand the biological jaw functions in early chondrichthyans, the animal class that includes sharks, skates, and rays.

The new study could also help scientists understand how this specialized combination of jaw motion and tooth placement was distributed across the shark family tree and figure out how the tooth clusters among modern shark species evolved.

Now that you’ve learned about how this prehistoric shark could rotate its jaw, read all about the megalodon, the prehistoric shark 10 times the size of a t-rex. Next, learn about the Greenland shark, the world’s longest-living vertebrate.