Sir John Franklin's expedition to the Northwest Passage was derailed by poisoning, murder, and cannibalism after his ships became trapped in Arctic ice.

In May 1845, 134 men embarked on a quest to find the elusive Northwest Passage, a lucrative trade route that could open Britain up to all of Asia — but they would never make it.

The Franklin Expedition, as it was called, was considered one of the best-prepared missions of its time. Captain Sir John Franklin had made several journeys into the Arctic and his ships, the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, were specially fortified to withstand the icy waves. Yet nothing could prepare this crew for what they were about to endure.

In July of that year, the Franklin Expedition disappeared. It would be another three years before the British took notice and launched a series of search parties — but to no avail. In the five years that followed, only three unmarked graves and a collection of the crew’s belongings were found on an uninhabited piece of ice. Those bodies showed signs of malnutrition, murder, and cannibalism.

It would be over a century before any more remains of the lost Franklin Expedition were finally discovered, and even then, those finds only raised more questions.

The Race To Find The Northwest Passage

Encyclopedia BritannicaThe Northwest Passage is easily traversable in modern day due to climate change.

Ever since the Greco-Roman geographer Ptolemy identified a northern waterway between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in the second century A.D., global powers searched desperately for it. The route, known as the Northwest Passage, would drastically streamline trade between Europe and East Asia. Consequently, kingdoms around the world launched lofty seafaring quests to find it.

By the 15th century, the Ottoman Empire had monopolized overland trade routes, which encouraged European powers to take to the sea in search of other routes, like the Northwest Passage. But from the 15th to the 19th centuries, that waterway was actually blocked in ice. Only in modern-day, with the effects of climate change and glacial melt, has that passage opened up.

Nonetheless, a centuries-long quest for this regional shortcut inspired countless attempts. Ironically, the Franklin Expedition would end in the discovery of the route as the search party that went after it in 1850 found it on foot.

But before that search party made their historic discovery, the British Navy tasked one man, 24 officers, and 110 sailors to find it.

The Franklin Expedition Prepares For Its Daunting Voyage

Wikimedia CommonsSir John Franklin was not only knighted, but became lieutenant governor of Tasmania.

Sir John Franklin was an esteemed Naval Officer and knight. He had been in battle, shipwrecked on a desolate Australian island, and most importantly, had surveyed substantial amounts of the North American coast as well as commanded several successful expeditions to the Arctic.

Meanwhile, Second Secretary of the Admiralty Sir John Barrow had been dispatching numerous expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage for the last 40 years. Many of those voyages had been successful in mapping the area, and at 82, Barrow felt his decades-long search was close to an end.

In 1845, Barrow contacted Franklin, whose experience made him a prime candidate for the quest. Despite the risks, the 59-year-old commander agreed.

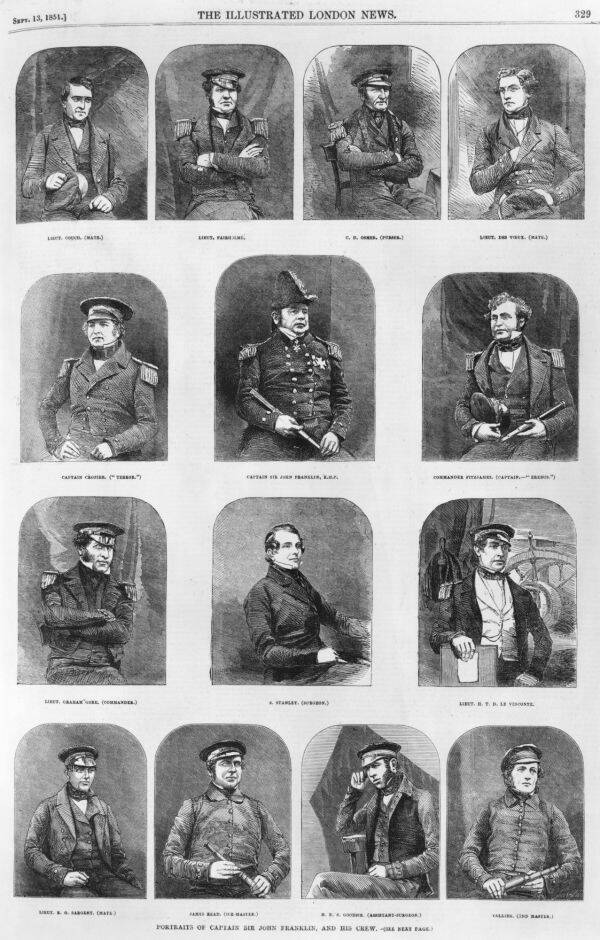

Illustrated London News/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesJohn Franklin and his crew, circa 1845.

The Franklin Expedition was set to depart from Greenhithe Harbor in Kent, England on May 19, 1845. Franklin would command the HMS Erebus and a Captain Francis Crozier would oversee the HMS Terror.

Both ships were equipped with iron-layered hulls and robust steam engines designed to withstand the intense Arctic ice. Both were also stocked with three years’ worth of food including 32,000 pounds of preserved meat, 1,000 pounds of raisins, and 580 gallons of pickles. The crew would also have a library at their disposal.

After departing from the River Thames, the ships made brief stops in Stromness, Scotland’s Orkney Islands, and the Whalefish Islands in Disko Bay on Greenland’s west coast. Here, the crew wrote their final letters home.

Wikimedia CommonsWilliam Smyth’s Perilous Position of the HMS Terror.

Those letters revealed that Franklin had banned drunkenness and swearing and sent five men home. Why the sailors were discharged remains unclear, though it could have been due to his stringent rules.

Before departing Disko Bay, the crew slaughtered 10 oxen to replenish their supply of fresh meat. It was late July 1845 when the Erebus and Terror crossed from Greenland to Canada’s Baffin Island and two whaling vessels saw them operational for the last time.

The Search Begins For The Lost Franklin Expedition

Wikimedia CommonsThe Arctic Council planning a search for Sir John Franklin by Stephen Pearce.

When Sir John Franklin’s wife had heard no news of her husband by 1848, she implored the Navy to launch a search brigade. Britain eventually obliged and hosted more than 40 expeditions to find the crew. Lady Franklin wrote a letter for each attempt to be handed to her husband when he was finally found, but no such trade-off happened.

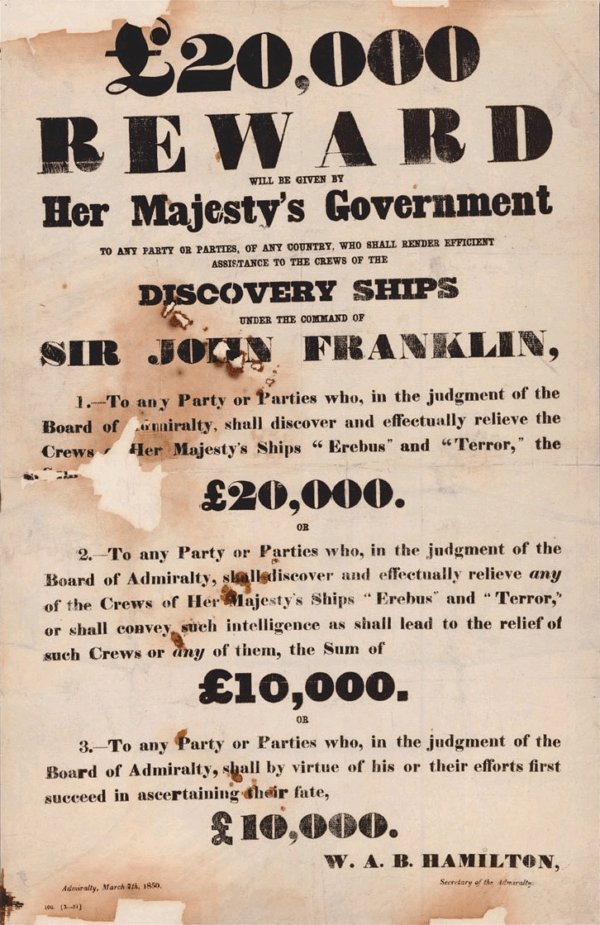

It wasn’t until 1850 that the first evidence of what happened to the Franklin Expedition was uncovered. As part of a joint effort between Britain and the U.S., 13 ships searched the Canadian Arctic for signs of life.

There, on an uninhabited stretch of land called Beechey Island, the search party found relics of a primitive camp and the graves of sailors John Hartnell, John Torrington, and William Braine. Though otherwise unmarked, the graves were dated 1846.

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1850 poster offers a lucrative reward to those who could find Franklin and his men.

Four years later, Scottish explorer John Rae met a group of Inuits in Pelly Bay who were in possession of some of the missing sailors’ belongings. The Inuits then pointed him toward a pile of human remains.

Rae observed that some of the bones were cracked in half and contained knife marks, which suggested that the starving sailors had resorted to cannibalism.

“From the mutilated state of many of the bodies, and the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last dread alternative as a means of sustaining life,” Rae wrote. He added that their bones were likely also boiled so that the marrow could be sucked out.

The mystery of what happened aboard Franklin’s expedition slowly began to unravel.

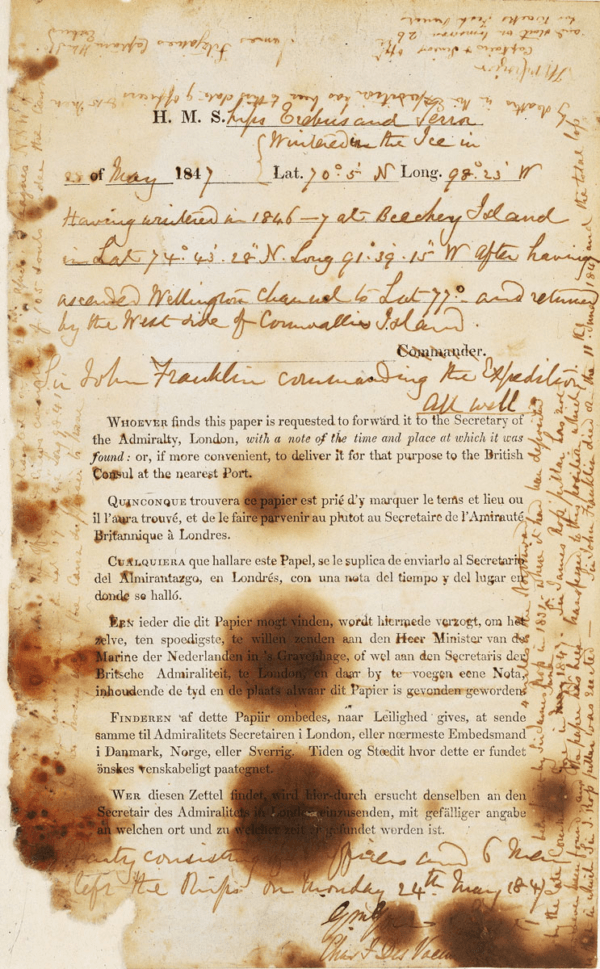

Then, in 1859, a note was discovered at Victory Point on King William Island by Francis Leopold McClintock’s rescue party. The letter, dated April 25, 1848, revealed that both ships at that time had been abandoned. It added that the 15 men and 90 officers who remained alive would walk to the Great Fish River the following day.

The note had also been written by Francis Crozier and stated that Crozier had taken command of the expedition after John Franklin died.

It would take nearly 140 more years for any further information to be uncovered regarding the fates of these men.

Corpses Show Signs Of Starvation And Poisoning

Canadian Museum of HistoryThe so-called “Victory Point note” written by Francis Crozier confirmed that at least 24 men had died by April 1848.

It has since become increasingly clear that the Franklin Expedition failed when the two ships became entrapped in ice. Once the food ran low, the crew likely got desperate, abandoned ship, and resolved to find help somewhere on the deserted Arctic wasteland just off the west coast of King William Island.

The men simply took their chances — and failed.

But there are even more disturbing details behind the failure of the Franklin Expedition and these became known in the ’80s.

In 1981, forensic anthropologist Owen Beattie founded the Franklin Expedition Forensic Anthropology Project (FEFAP) in an attempt to identify which crewmen had died and been buried on King William Island.

Wikimedia CommonsThe three corpses were buried under more than five feet of permafrost.

The bodies of Hartnell, Braine, and Torrington were exhumed and analyzed in 1984. Torrington was found with his milky-blue eyes wide open and with no wounds or signs of trauma on his person. His 88-pound body did, however, show signs of malnourishment, deadly levels of lead, and pneumonia — which scholars believe afflicted most, if not all of the men. Beattie theorized that the lead poisoning was likely due to improperly or poorly tinned rations.

Because their expedition required so much food, Beattie posited that the man responsible for tinning all 8,000 cans of it had done so “sloppily” and that lead likely “dripped like melted candle wax down the inside surface,” poisoning the men.

The bodies were also all found to be suffering from extreme Vitamin C deficiencies, which would have led to scurvy. The following year, Beattie’s team discovered the remains of between six and 14 more people on King William Island.

Discovering The Terror And Erebus

But while the crew was found, the ships remained at large for nearly another two decades. Then, in 2014, Parks Canada found the Erebus in 36 feet of water off King William Island.

Brian SpenceleyJohn Hartnell, exhumed on Beechey Island.

The Terror was located by the Arctic Research Foundation in 2016 in a bay 45 miles away that was aptly named Terror Bay. Strangely, neither ship showed any damage as both their hulls were intact. How they separated and then sank remains a mystery.

But experts can hypothesize and they believe that with no way of traversing through the ice, Franklin and his men were forced to abandon ship. The vessels were intact, but utterly useless in the insurmountable terrain. With nothing but a desolate wasteland to trek through — everyone died over the next few months.

All the unearthed items were officially transferred to the National Maritime Museum in 1936 and those two ships remain on the Arctic floor where they have since been studied. Eerily, all of the doors on the Terror were left wide open, save for the captain’s.

In the end, all that’s left of the lost Franklin Expedition are a few relics, two shipwrecks, and the pristinely preserved bodies of three sailors fortunate enough to have been buried before they could have been eaten by their peers.

After learning about the lost Franklin Expedition of 1848, read about 11 sunken ships from around the world. Then, check out seven true scary stories that are stranger — and more horrifying — than fiction.