It took a century for scientists to figure out the reason for Blood Falls' crimson water — and how it flows out of the glacier.

Peter Rejcek, National Science FoundationThe blood-colored waterfall of Blood Falls on Taylor Glacier.

During the British Terra Nova Expedition in 1911, geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor came across a terrifying sight. While exploring what is now known as Taylor Glacier in Taylor Valley, both located in East Antarctica, Taylor discovered a vivid red outflow seeping from the terminus of the glacier. Taylor named the curious crimson waterfall “Blood Falls.”

Despite looking like something out of H. P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, however, Blood Falls’ eerie redness has a perfectly logical explanation. At the time, Taylor and his contemporaries theorized that the red coloration could be the result of red algae, but later research found that the hue was the result of iron-rich, hypersaline water.

Even with that explanation, though, there is still much about the seemingly bleeding glacier that continues to capture scientists’ attention.

The Discovery And Initial Mystery Of Blood Falls

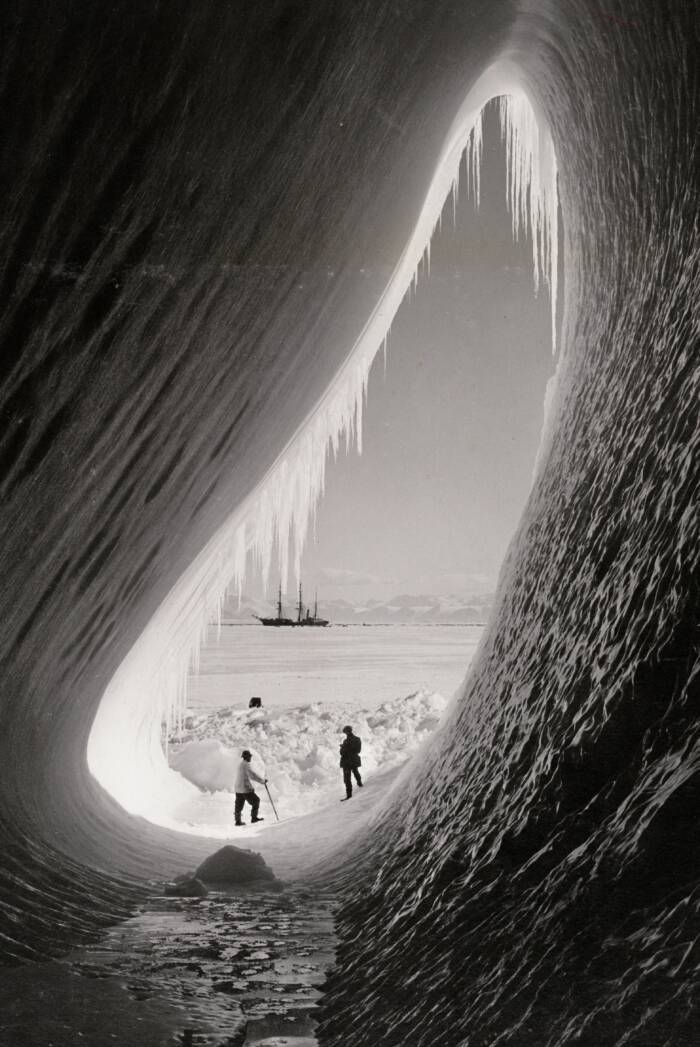

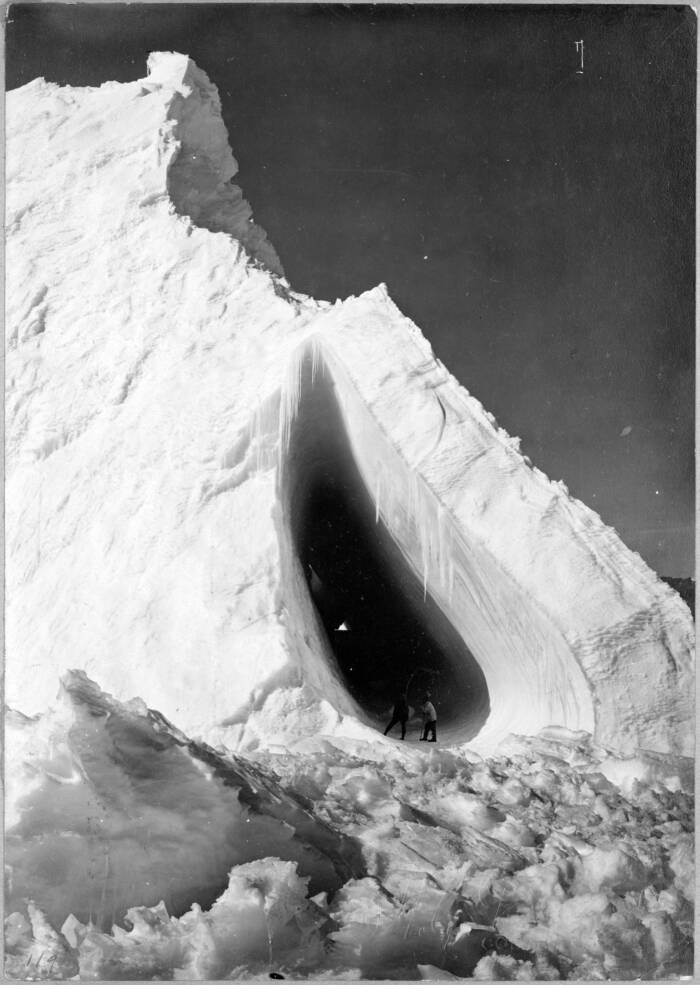

The Terra Nova Expedition, a.k.a. the British Antarctic Expedition, was a mission led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott between 1910 and 1913 with the primary goal of being the first to reach the geographic South Pole. That said, the expedition also sought to conduct geological and biological research.

It set sail from Cardiff, Wales, on June 15, 1910, aboard the ship Terra Nova. After stops in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand for fundraising and supplies, the team reached Ross Island in Antarctica in early January 1911 and established a base at Cape Evans.

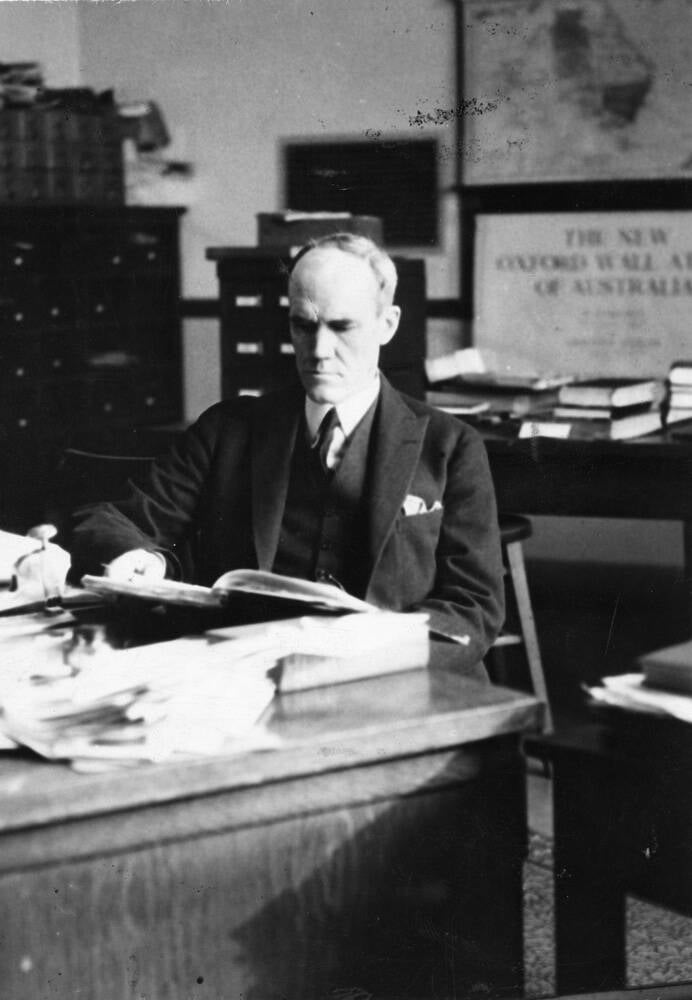

Public DomainThomas Griffith Taylor, who discovered Blood Falls, was a survivor of the Terra Nova expedition — from the ship Terra Nova — which sought to both explore Antarctica and reach the South Pole.

The group was split into several sections. Scott's team would ultimately reach the South Pole on Jan. 17, 1912, only to find that a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen had beaten them there 34 days earlier. They tragically died during their return trip, with Scott's final journal entry dated March 29.

However, the two other Terra Nova Expedition groups had better luck. One spent the winter of 1911 in a hut at Robertson Bay, and the latter half of the expedition near Evans Cove. The other, which included Taylor, set out to conduct a geological survey along a coastal area west of McMurdo Sound.

During this expedition, Taylor discovered a glacier flowing in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, a region unusually lacking in snow and ice cover. The glacier was subsequently named "Taylor Glacier," and the nearby valley "Taylor Valley."

Public DomainBack row: Robert Forde and Tryggve Gran. Seated: Frank Debenham and Thomas Griffith Taylor.

While studying Taylor Glacier, Taylor's team observed a peculiar phenomenon at its terminus: a waterfall of crimson water seeping from the glacier and into Lake Bonney. It looked disturbingly like blood, and was especially striking in contrast with the stark whiteness of Antarctica. Taylor dubbed the strange natural phenomenon "Blood Falls."

Although the sight was unsettling, Taylor and his team were men of science. They took extensive notes, observations that would later offer great contributions to the fields of glaciology and geology, and attempted to figure out why Blood Falls' water was such a stark color of red.

With their limited resources, Taylor concluded that red algae must be behind Blood Falls' strange hue. More than a century later, however, new research would reveal the real reason for the red waterfall in Antarctica.

Why Is Blood Falls Red? Inside The Scientific Research

Ariel Waldman/Flickr Creative CommonsAntarctica's eerie "Blood Falls" gets its red color from iron in the water.

More than a century after Taylor first documented Blood Falls, a group of scientists published a study in the Journal of Glaciology which explained what made Taylor Glacier "bleed" red water.

Building upon previous studies which had found a network of briny groundwater underneath Taylor Glacier, the researchers discovered that this briny groundwater fed into to the glacier's waterfall. They also found that the water was packed full of iron, and when this iron-rich water hits the air, it oxidizes and turns red. Thus, this is what gives Blood Falls its red color.

"[T]he brine discharges at the surface on the northern side of Taylor Glacier staining the ice red and depositing a red-orange apron of frozen brine," the researchers explained in their study about Blood Falls. "The red color results from iron oxides precipitating when the iron-bearing suboxic brine comes in contact with oxygen in the atmosphere."

Wikimedia CommonsAn aerial view of Blood Falls.

With that, the red color of Blood Falls had been solved. But it wasn't the only mystery that the researchers considered during their study. Certainly, the bloody color of the waterfall was the most eye-catching thing about the glacier, but the researchers also sought to find out why the water of Blood Falls was able to flow like a waterfall, and not freeze in the ice.

During the course of their study, they solved this mystery as well.

How Does Taylor Glacier's Water Remain Liquid?

Given the frigid Antarctic temperatures, running liquid water might seem an odd occurrence — especially flowing from a glacier as Blood Falls flows from Taylor Glacier. Once again, however, the flow of Blood Falls' red water can be attributed to its briny composition.

Even though Taylor Glacier is frozen all the way to the ground, and even though the temperature of its ice is far beneath the freezing point of 32 degrees Fahrenheit, its briny groundwater behaves differently than the glacial ice. Saltwater has a lower freezing point than freshwater and, since it releases heat as it freezes, it melts the ice. This, in turn, allows Blood Falls to flow from the glacier like a slow-moving waterfall.

"While it sounds counterintuitive, water releases heat as it freezes, and that heat warms the surrounding colder ice," study lead author Jessica Badgeley explained in a 2017 statement about the discovery. She added: "Taylor Glacier is now the coldest known glacier to have persistently flowing water."

Shockingly, this environment also allows for life — albeit on a microscopic scale. In fact, a study published in Nature Communications a full two years before Badgeley's study had found that Blood Falls contained microbes living in extreme conditions in a way unobserved elsewhere on Earth.

Cavan Images / Alamy Stock PhotoBlood Falls as seen on Taylor Glacier.

That study also found that the water gushing out of Taylor Glacier was just the mouth of a system of aquifers that went down 600 feet beneath the surface. Based on this, experts believe it is likely that there is a deep, underground reservoir of salty water beneath the Antarctic permafrost. Though scientists have been able to trace some of this underground reservoir with electromagnetic pulses, the glacier's thick ice makes it difficult to gauge its depth. It likely goes deeper than they can detect.

Lead author Jill Mickuki told the Washington Post in 2015 that this discovery could also have implications for potential life on other planets. She remarked: "The subsurface is actually pretty attractive when you think about life on other planets. It's cold and dark and has all these strikes against it, but it's protected from the harsh environment on the surface."

As such, Blood Falls turned out to be even more fascinating than Thomas Griffith Taylor originally speculated. Far from being colored by algae, its color comes from an incredible hidden network of subglacial rivers and lakes, an wildly unique environment that we're just beginning to understand.

After reading about the mystery of Antarctica's Blood Falls, discover the stories of some of the coldest places on Earth. Or, go inside the strange story of Operation Highjump, the secretive U.S. mission to explore Antarctica that has inspired some wild conspiracy theories.