The Great Blizzard of 1888 tore through the Eastern Seaboard without warning that March, severing telegraph lines, stranding thousands of passengers on elevated trains, and killing roughly 400 people.

The Blizzard of 1888, also known as “The Great White Hurricane,” swept across the northeastern United States in March, wreaking havoc across cities and rural areas alike. It stands as one of the most extreme weather events in American history — and we’re still feeling its impact.

The record-breaking storm began on March 11, 1888 and caught the East Coast entirely off-guard. As the country neared springtime, the weather had been unseasonably warm, and most assumed that winter was all but over.

Then, the Blizzard of 1888 struck.

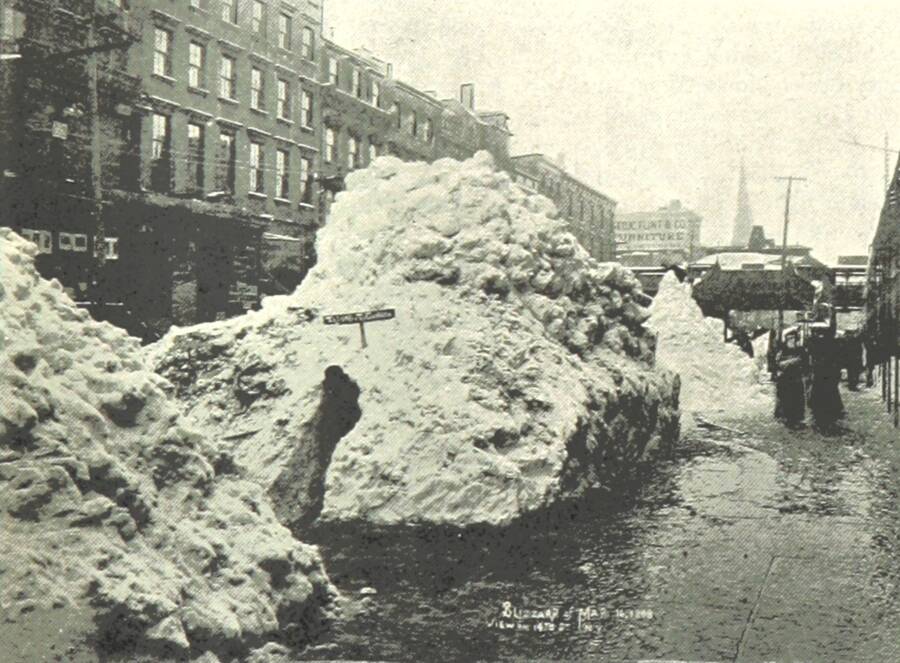

The devastating storm ultimately reshaped how cities managed weather-related emergencies, and influenced the evolution of infrastructure, public safety measures, and communication. Look through photos of the blizzard below, and read on to see how it transformed the United States.

The Blizzard Of 1888 — A Sudden, Unforgiving Storm

On the day before the Blizzard of 1888 began, most people in the northeast woke up to mild, rainy conditions. Temperatures hovered in the mid-50s on March 10, 1888 and, without the weather tracking technology that exists today, there was no sign that things were about to drastically change.

But on the next day, Arctic air from the north collided with warmer air from the Gulf. This caused temperatures to plunge, and the heavy rain that had been falling in New York City turned to snow at 1 a.m. on Monday, March 12.

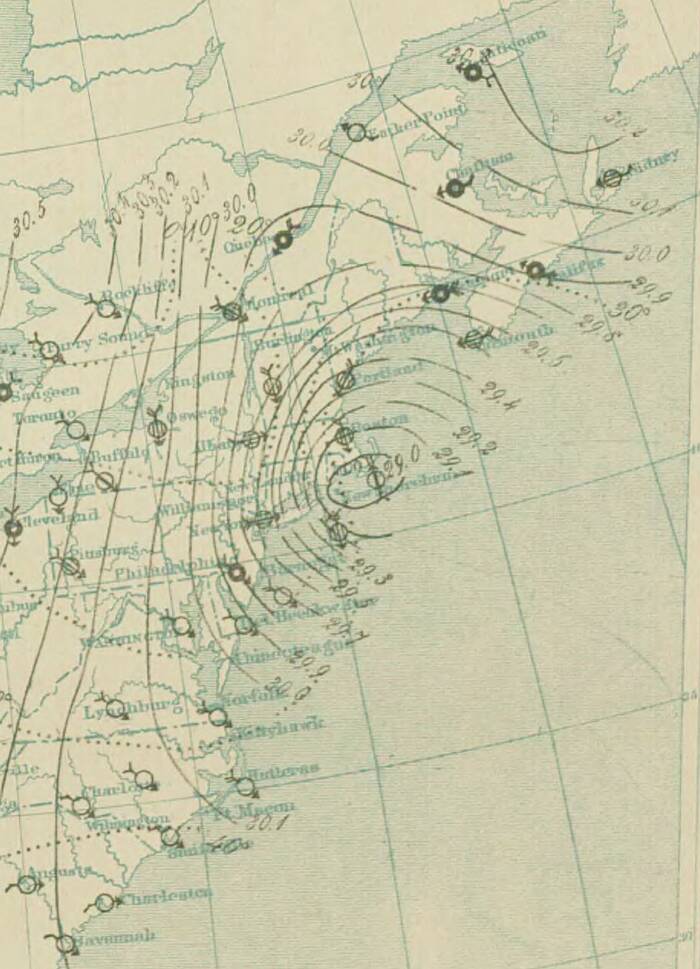

As the Weather Underground reported in 2020, the Blizzard of 1888 was no ordinary storm. Usually, a cold front in New England or southern Canada would herald such an event; no such cold front appeared. And unlike most storms, which move, this one became stationary before making a counterclockwise loop. All the while, it maintained its intensity.

Public DomainAn illustrated overview of the area affected by the Blizzard of '88.

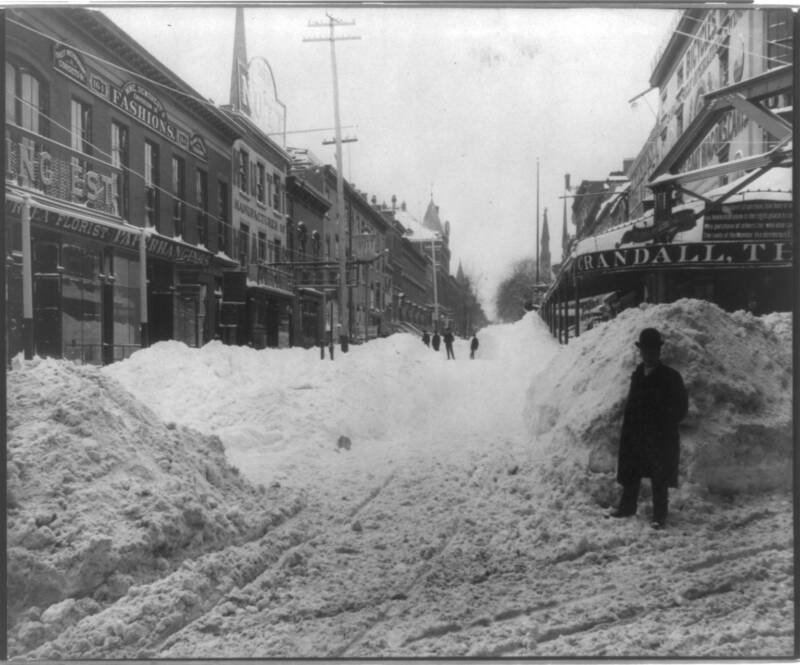

This was, effectively, a recipe for a weather disaster. For three days, the northeast was rattled by 85 mile-per-hour winds and snow which fell in feet, not inches. Almost two feet of snow fell in New York City, and other place got nearly four feet of snow. Even cities and towns accustomed to snowfall had never seen anything like the Blizzard of 1888.

How The Devastating Blizzard Impacted Cities Up And Down The Eastern Seaboard

The storm created a winter wasteland that paralyzed one of the most densely populated parts of the country. At the time, one in four Americans lived on the East Coast. And most of them — save the very wealthy — had to grapple with the storm in one way or another.

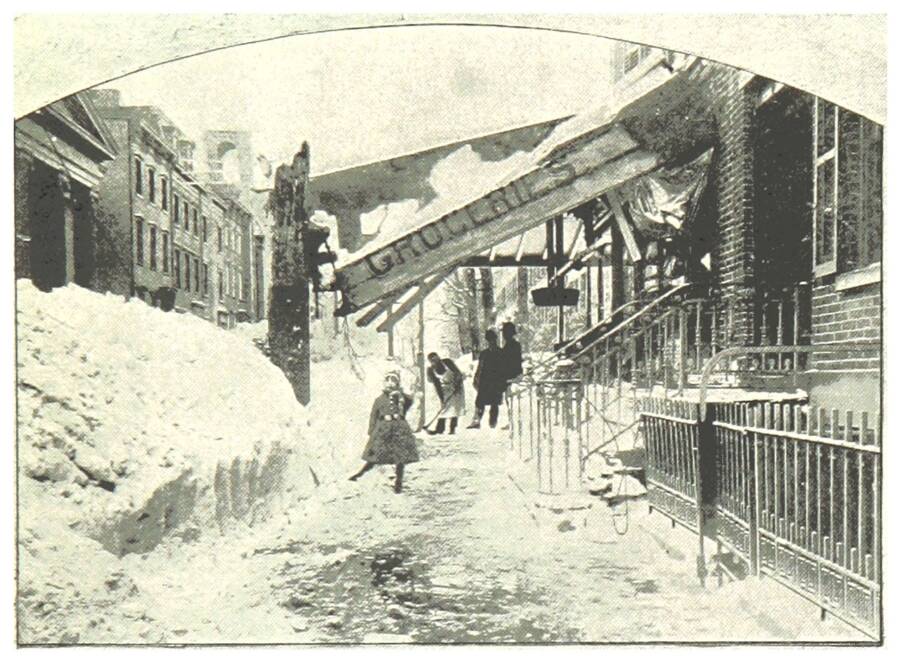

In New York, the city's elevated trains ground to a halt. Some 15,000 people became stranded, as the trains were blocked by snow drifts nearly two stories high. Shops and businesses closed, and places like Wall Street and the Brooklyn Bridge were forced to shut down. The East River even froze, making passage by ferry impossible. Though some people tried to cross the river to get to work on foot, many of them ended up stuck on ice floes.

Public DomainA collapsed awning in New York City during the Blizzard of 1888.

Meanwhile, the cold and wind had severed telegraph wires, which meant that major cities suddenly couldn't communicate with the rest of the country. The National Museum of American History reports that Boston's Daily Globe printed the grim headline "Cut Off." Elsewhere, farmers in more rural areas lost thousands of animals to the blizzard.

People were stranded in shops, bars, and anywhere else they could find. The writer Mark Twain, for example, was stuck at his hotel for several days. But they were the lucky ones. Some 400 people died during the Blizzard of 1888, including 200 people in New York City. One of the most famous people to perish was Roscoe Conkling, a senator with presidential aspirations, who died while trying to walk from Wall Street to Madison Square.

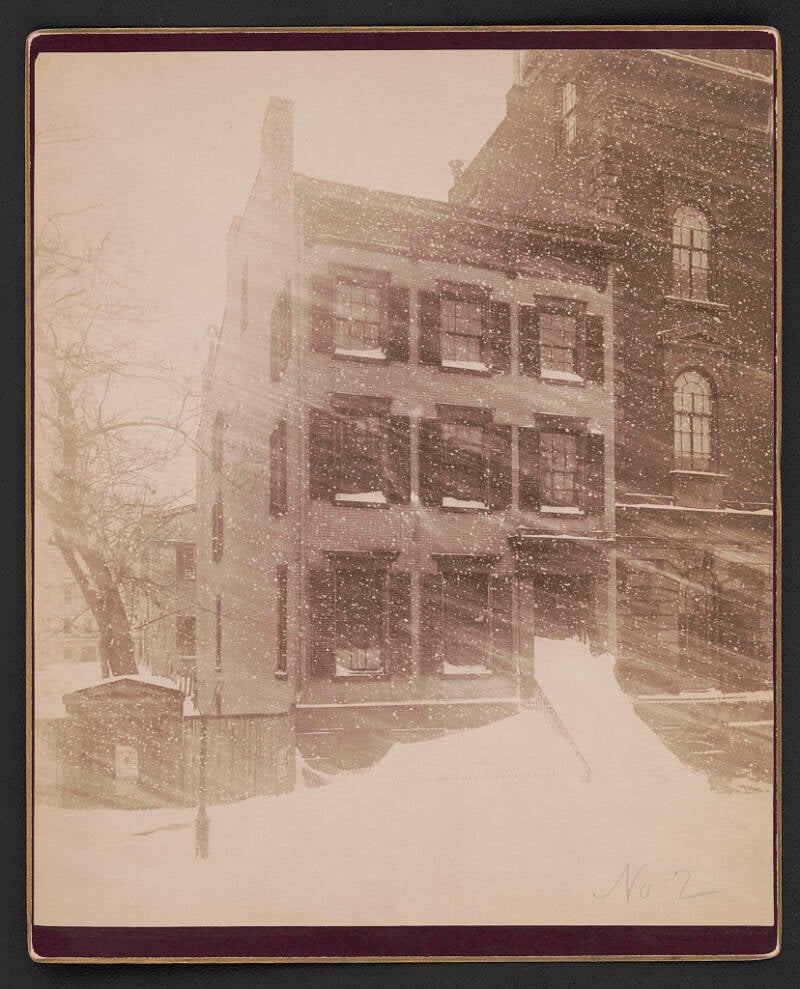

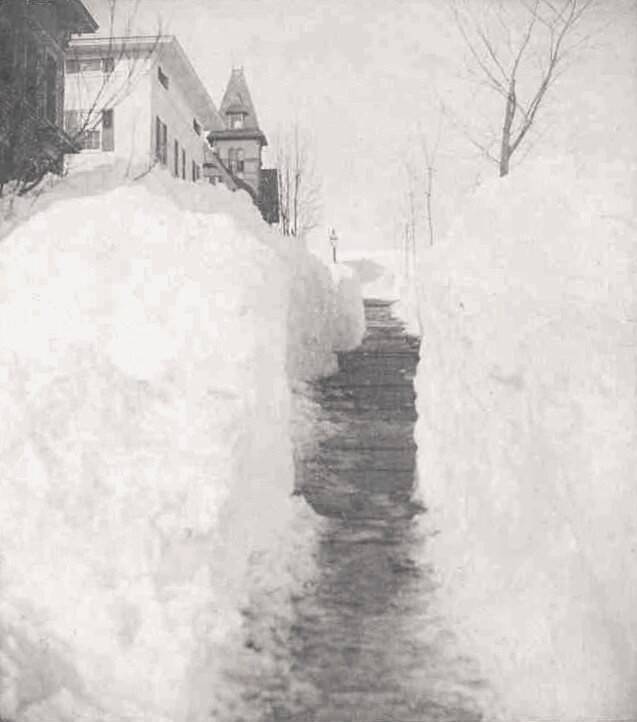

Public DomainA snowy scene in New Britain, Connecticut. March 13, 1888.

By March 14, the snow had begun to melt. By March 15, the New York Stock Exchange, forced to close during the blizzard, reopened, and many of New York City's trains began to move.

The storm had passed. But its impact would be deeply felt.

The Immediate Aftermath Of The 'Great White Hurricane'

The storm caused severe infrastructural damage across the Eastern Seaboard, trapping people indoors for days, often without adequate food or supplies. Telegraph lines, water lines, gas lines, and, importantly, the elevated train lines, had all been paralyzed during the blizzard. In New York City alone, it caused a reported $20 million in damages.

Parts of Brooklyn flooded; the New York City Stock exchange had been forced to shut down for two days; and many other factories, businesses, and stores were also forced to close, resulting in a huge loss of revenue.

Elsewhere, smaller cities like New Haven, Connecticut, and Keene, New Hampshire, reeled to recover from the intense snowfall. And even those not on land suffered terribly — the storm sunk hundreds of boats which were trapped in the Atlantic during the blizzard, killing roughly 100 sailors.

Public DomainA house in Keene, New Hampshire, during the Blizzard of 1888.

It took weeks for the region to recover. And in the aftermath, many began to think about how cities could be improved to handle extreme weather conditions in the future.

How The Blizzard Of 1888 Transformed Public Infrastructure

One of the main impacts of the Blizzard of 1888 was on public infrastructure. The storm had utterly paralyzed public utilities, especially elevated trains. As such, an effort began to move these underground.

City planners began work on designs for an underground subway system shortly after the blizzard hit. In 1901, America's first underground train system opened in Boston. New York City followed suit and opened its own subway in 1904. Meanwhile, major cities' telegraph and telephone lines were also moved underground to prevent disruptions from future storms.

Public DomainPart of the City Hall subway station that opened in New York City.

Another comparable snowstorm wouldn't come to the region for another 90 years, when the Blizzard of 1978 raged for 32 hours, causing flooding and property damage to thousands of homes. However, thanks to the modern advancements inspired by the Blizzard of 1888 — like underground subway, rail, and telephone lines — the impact of the 1978 storm was far less severe than that of the storm that had devastated the area nearly a century before.

But it would certainly leave an impact on the people who survived it. Until 1969, survivors met in New York City to swap stories about the Blizzard of 1888. They shared memories like walking across the East River, or being rescued from snow drifts. And when other storms threatened the region, as one did in 1934, they were quick to dismiss them as insignificant as compared with 1888. One ditty written by a survivor goes:

"Our blizzard sure must take the prize,

In spite of all the years and lies;

Our snow was nearly two feet deep,

Piled up and down in one big heap."

After this look at the Blizzard of 1888, see some surreal photos from the Boston molasses disaster of 1919. Then, read up on Mount Pelee and the most devastating volcanic eruption of the 20th century.