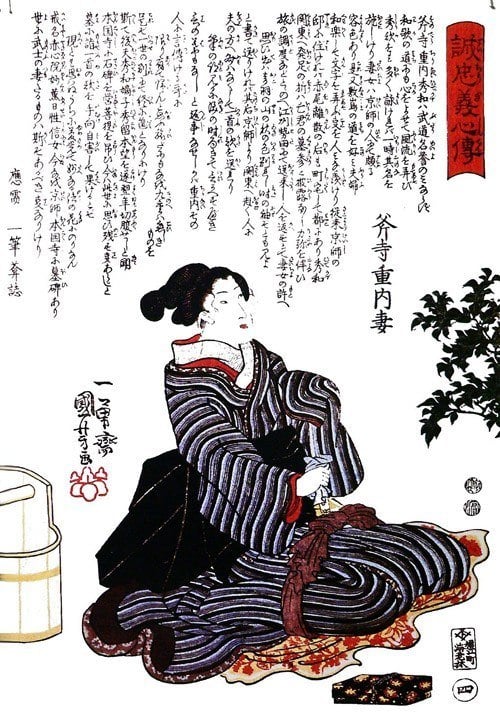

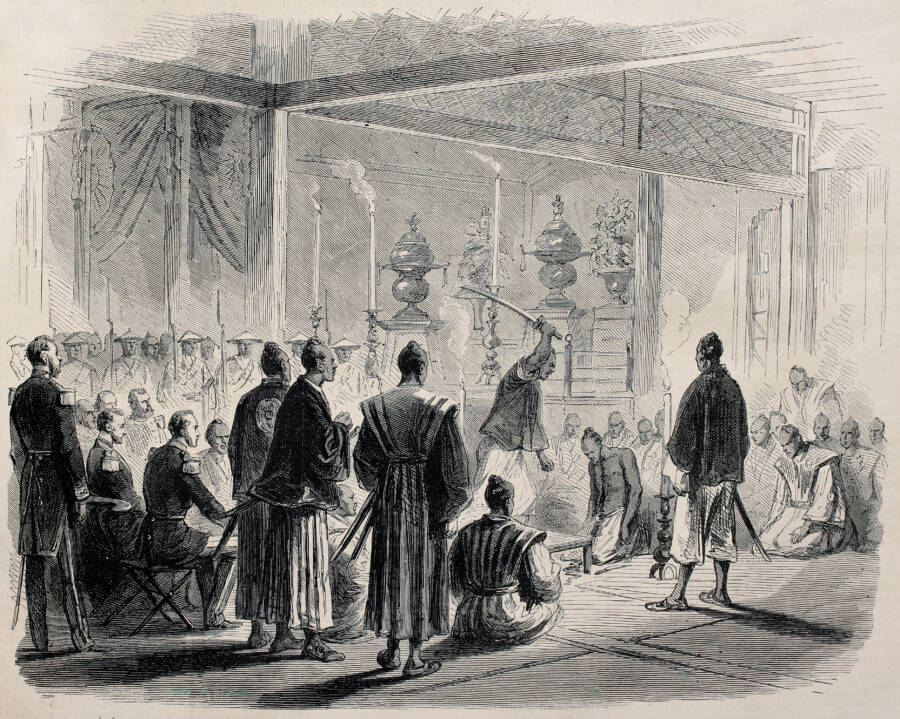

Traditionally, seppuku involved a samurai slicing through his own abdomen in a slow and excruciating death, but in later years, a second person would cut off the victim's head at the moment of highest agony.

Japanese samurai were among history’s most powerful and noble warriors. They lived by a moral code known as bushidō, and loyalty and honor were core tenets of their being. That sense of honor followed a samurai throughout his life — and even, in some instances, his death.

When facing defeat, for example, a samurai might die by seppuku, also known as harakiri, a form of ritual suicide performed by slicing one's own abdomen horizontally with a blade. Although the exact origins of this grisly act are unclear, seppuku likely began around the late 12th century.

Over the following centuries, seppuku started to evolve into something else, however. During the Edo period, an elaborate ritual formed around the act. It also became a form of capital punishment.

Obligatory seppuku was abolished in Japan in 1873, and voluntary suicide by disembowelment also waned as the age of the samurai came to an end in the late 19th century. However, several other instances of seppuku have been recorded since — including as recently as 2001.

Above, look through 32 revealing photos of seppuku. And below, read more about the gruesome history of the act.

The Medieval Origins Of Seppuku

Despite being intrinsically linked to the samurai code, seppuku did not begin with the samurai — at least, so long as legend is to be believed. According to nippon.com, the first instance of seppuku allegedly dates back to 988 C.E., when a bandit by the name of Hakamadare was said to have slashed open his stomach after being caught. However, there is no real evidence that Hakamadare actually did this, and since he was a thief and not a samurai, it would be somewhat untruthful to say his death marked the beginning of seppuku.

Rather, University of Tokyo professor Yamamoto Hirofumi suggests seppuku's true origins came about 200 years later, in 1189. Following the Genpei War — a civil war between Japan's Taira and Minamoto clans that ended with the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate — commander Minamoto no Yoshitsune was facing defeat with no option to retreat.

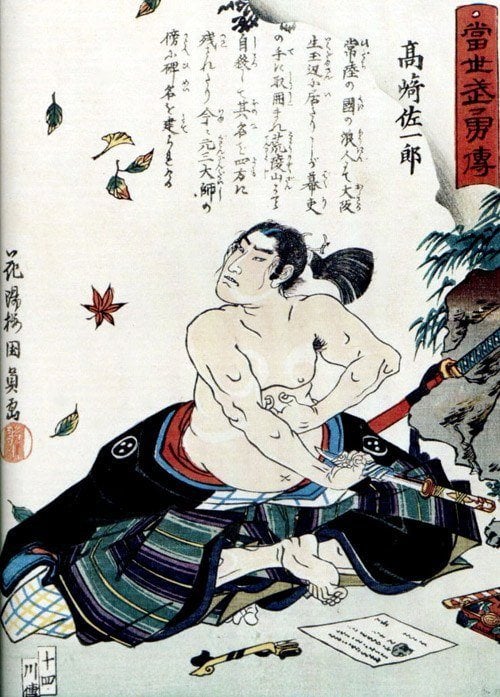

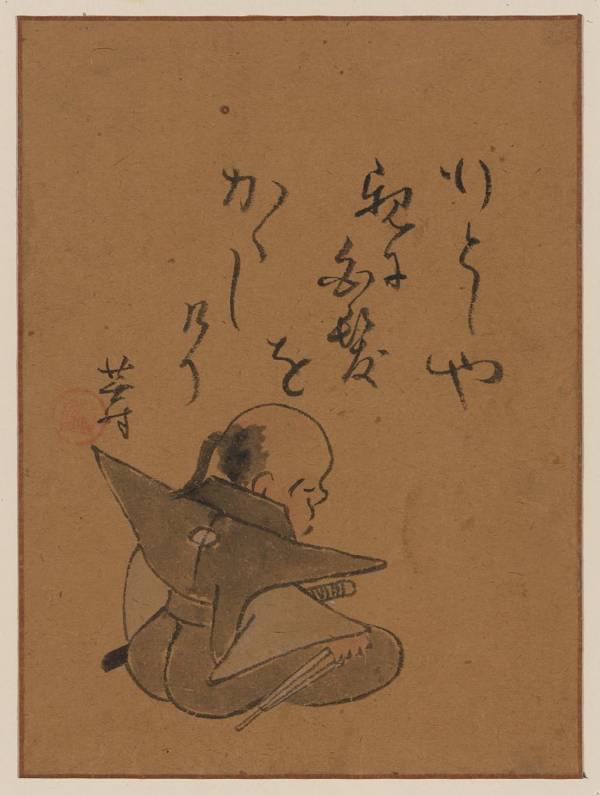

RijksmuseumA color woodcut of Minamoto no Shitsune during the Genpei War. 1853.

Not willing to surrender himself to the forces that overwhelmed him, Yoshitsune chose to take his own life, plunging a knife into his stomach and slicing it open. His death was seen as an honorable way to die, a demise that wiped away the disgrace of defeat.

Dying in battle was courageous, but running away was seen as a coward's option. By taking one's own life, a samurai was making a final, painful choice about how he died. Seppuku embodied the bushidō code of honor, courage, and self-sacrifice, and the grisly practice continued to be seen in such a manner throughout the medieval era. However, during the Warring States period (1467 to 1568), that would change.

How Seppuku Transformed Over The Centuries

The Warring States period — or the Sengoku period — was a time in Japanese history plagued by almost continuous civil wars throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. Feudal lords turned on each other and the emperor, each vying to control Japan. Vassals betrayed their lords, hoping to come into power of their own. It was a time of political chaos and mass social unrest.

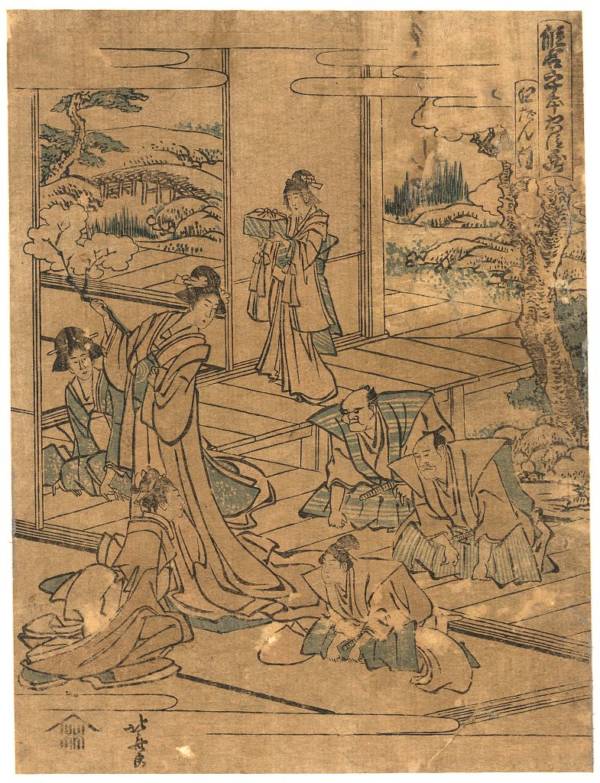

Public DomainA depiction of the Ōnin War, which took place between 1467 and 1477 during the Warring States period in Japan.

Given the tumultuous nature of the times, the life of a samurai was a busy, violent one. But the samurai code had not changed, and an honorable death was still sought after. However, seppuku was no longer just a means for a warrior to retain his honor in death; it started being seen as a way for a military leader to save the lives of his retainers, the samurai who provided him with military services.

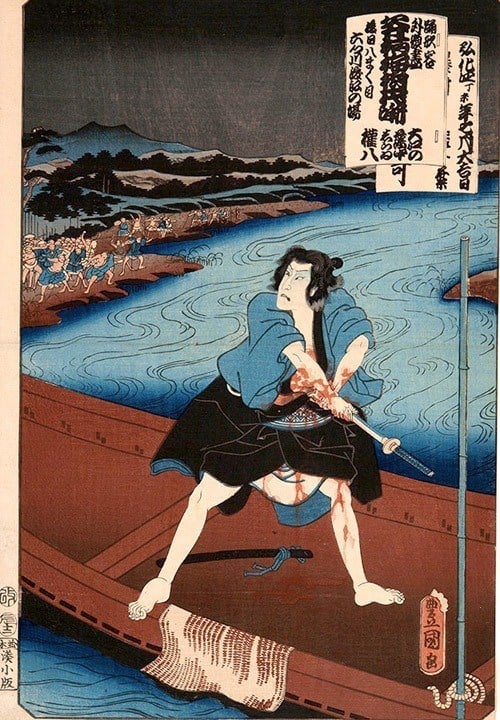

One of the most famous examples of this sacrificial seppuku occurred in June 1582. Hashiba Hideyoshi's forces sieged the castle of Shimizu Muneharu, intentionally diverting a river to flood the palace. Muneharu, realizing defeat was imminent, struck a deal of sorts with Hideyoshi: If Muneharu would die by seppuku, no one else would be killed.

Muneharu boarded a small boat and sailed out of the flooded castle. There, in the middle of the water, he plunged a knife into his stomach, and his people were spared.

His sacrifice was seen as a noble one, and it was slowly adopted by other military leaders who would sacrifice their own lives to protect their people. This turbulent, war-torn period eventually came to an end, however. Once the conflict was over, an era of peace was ushered in, and with it, a new evolution of seppuku.

Seppuku As Capital Punishment During The Edo Period

Until the Edo period, seppuku had been a voluntary act, an honorable way out for samurai in dire situations. However, now that Japan's constant infighting had come to an end, the role of samurai in society began to change as well. Rather than serving as a military force, samurai instead took roles as civil servants, teachers, clerks, and bureaucrats in the Tokugawa shogunate.

But they were still bound by a code, and with that came certain expectations of how they should behave. As such, there needed to be justice for any samurai who broke his code — and seppuku was as fitting a punishment as any.

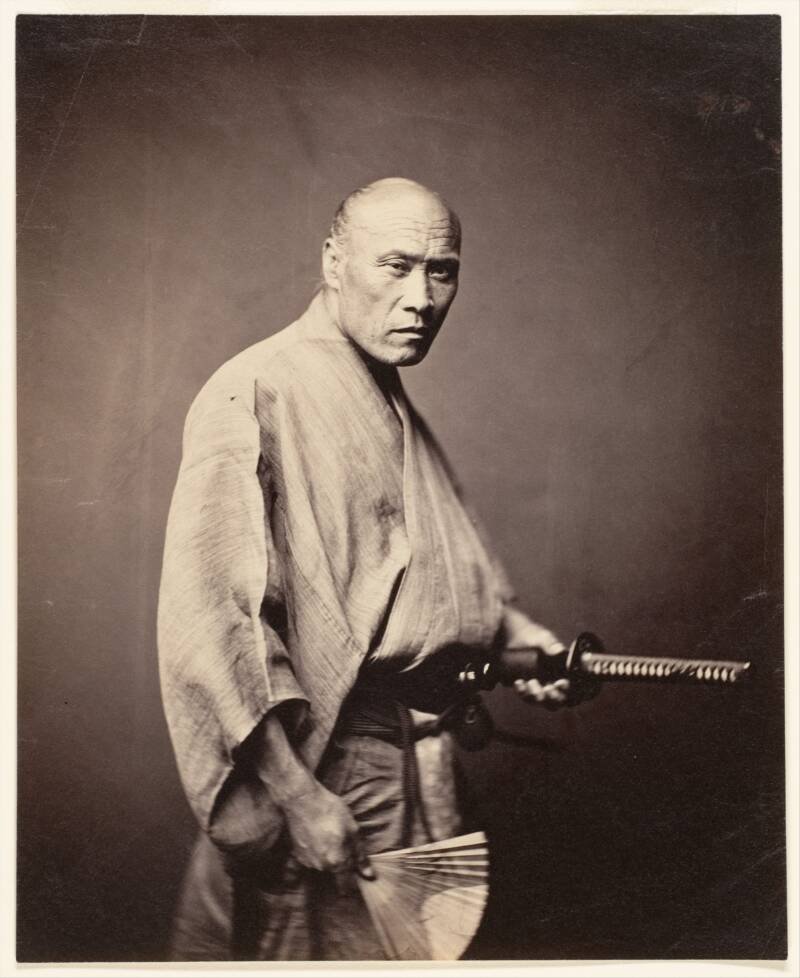

Metropolitan Museum of ArtA samurai poses for a photo circa 1864, just before the end of Japan's feudal period.

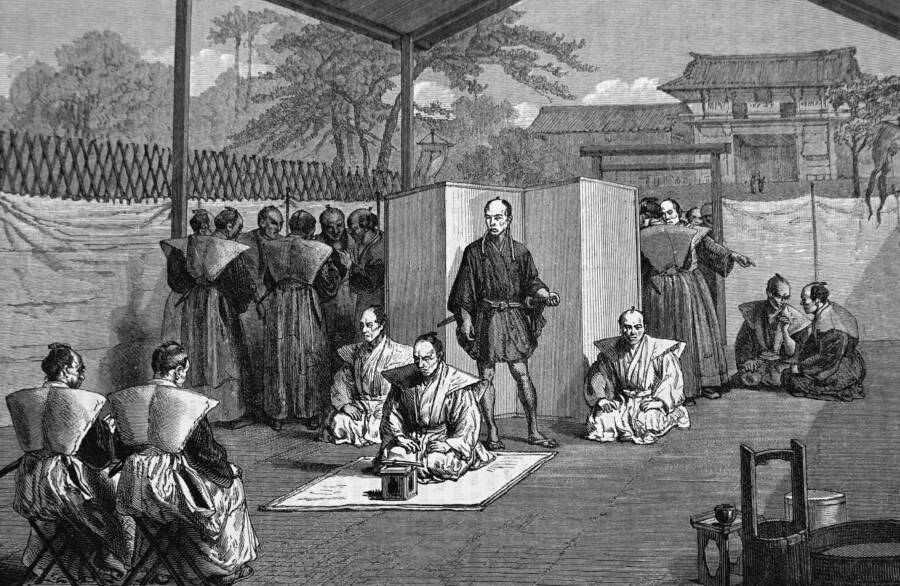

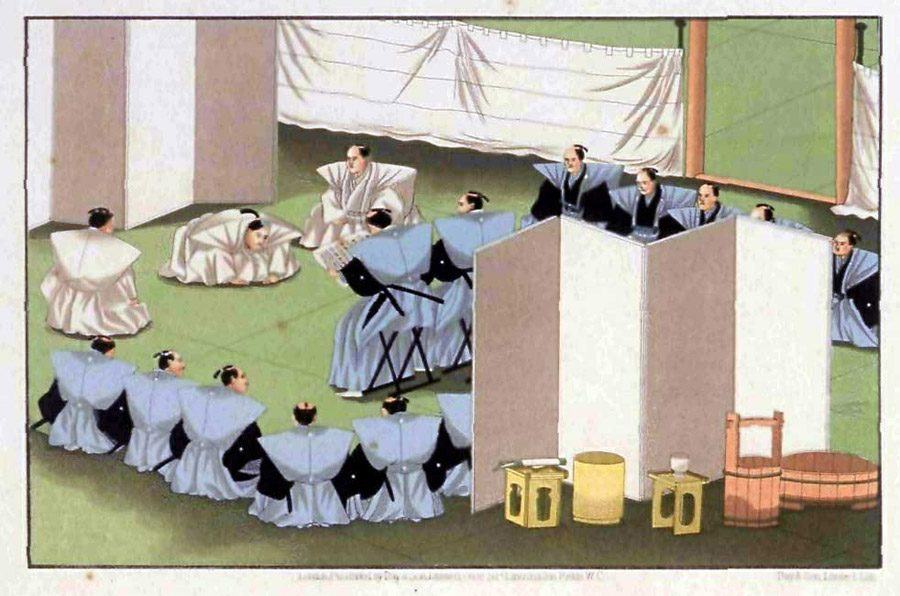

The biggest change during the Edo period, however, was that seppuku was not always a voluntary act. It was also a forced form of execution, ordered by the shogunate for any samurai who violated laws or feudal codes. Dishonorable acts or offenses brought shame not just to the samurai who committed them but also to his lord. Seppuku, as always, was seen as a way for the samurai to restore his honor.

During this period, other elements of the ritual evolved, too. Someone forced to die by seppuku would do so publicly dressed in a white robe. They were to face their death with dignity and stoicism in hopes of regaining their honor, and once the deed was done, a kaishakunin would step forward and behead the newly atoned samurai — though some records claim they would not remove the head completely.

Seppuku was essentially the most extreme example of devotion to the bushidō code, a representation of the strict ideals of feudal Japan. But that feudal structure ultimately came to an end in the late 19th century.

Death By Disembowelment In Post-Feudal Japan

In 1871, feudalism in Japan officially came to an end — and with it, the reign of the samurai. That said, bushidō did not disappear entirely. It became the ruling moral code of Japan, which is why, during World War II, Japanese soldiers equipped themselves with samurai swords to make suicidal banzai attacks.

In fact, in July 1945, TIME shared the account of a soldier who witnessed the deaths of Japanese generals Mitsuru Ushijima and Isamu Cho — brutal deaths that harkened back to the age of the samurai:

"Ushijima's aide stepped forward, bowed, handed each General a gleaming knife. The knives had been half covered with white cloth, so that the aide did not touch the sacred metal.

The Generals opened their blouses, unbuckled their belts. Ushijima leaned forward and with both hands pressed the blade against his belly. One of his adjutants did not wait for the knife to plunge deep. With his razor-sharp saber he lopped off his superior's head. General Cho leaned forward against his blade. The adjutant swung again. Orderlies took the bodies away.

General Cho had left his own epitaph: 'Twenty-second day, sixth month, 20th year of Showa era. I depart without regret, fear, shame or obligation. Age on departure 51 years.'"

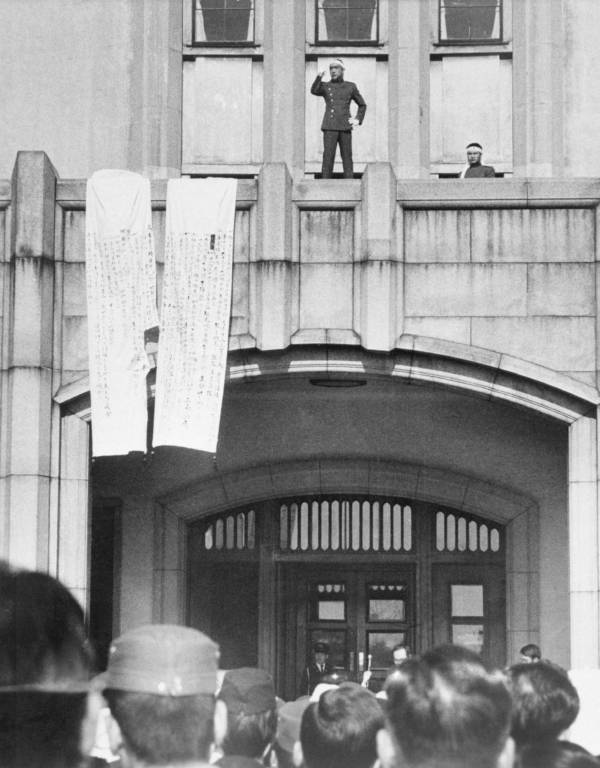

There have even been several recorded instances of seppuku in modern times. Perhaps the most famous case was that of Yukio Mishima, a Japanese author who believed that Japan was straying too far from its traditional roots. He attempted to stage a coup to overthrow the country's post-war government. When he failed, he disemboweled himself after shouting, "Long live the Emperor!"

National Archive of the Netherlands/Wikimedia CommonsNovelist Yukio Mishima just moments before he died by seppuku in 1970.

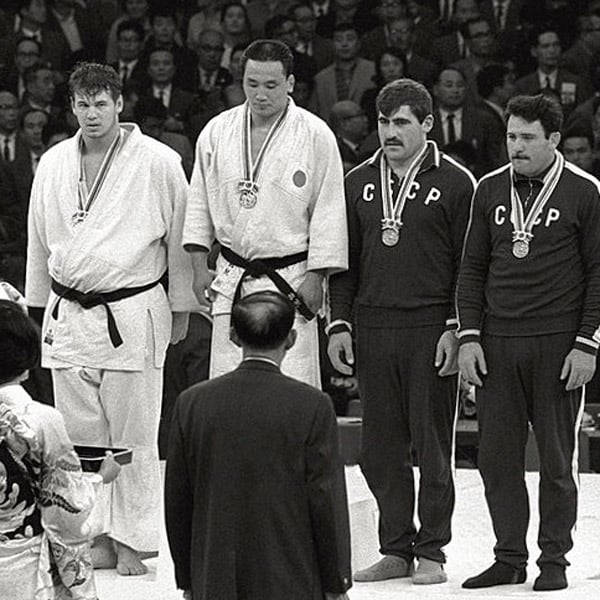

And in 2001, Isao Inokuma, an Olympic gold medalist in judo, took his own life by seppuku, seemingly because his construction company was failing.

Ultimately, although seppuku may seem gruesome to Westerners, the act represented the deeply ingrained cultural ideals of feudal Japan that altered the course of the nation's history.

After learning about the history of seppuku, look through even more photos of Imperial Japan. Then, read about Miyamoto Musashi, the legendary samurai of Edo Japan.

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or use their 24/7 Lifeline Crisis Chat.