During the summer of 1877, about 100,000 workers across the U.S. banded together to protest wage cuts at the nation's major railroad companies — but the massive strike was over almost as quickly as it began.

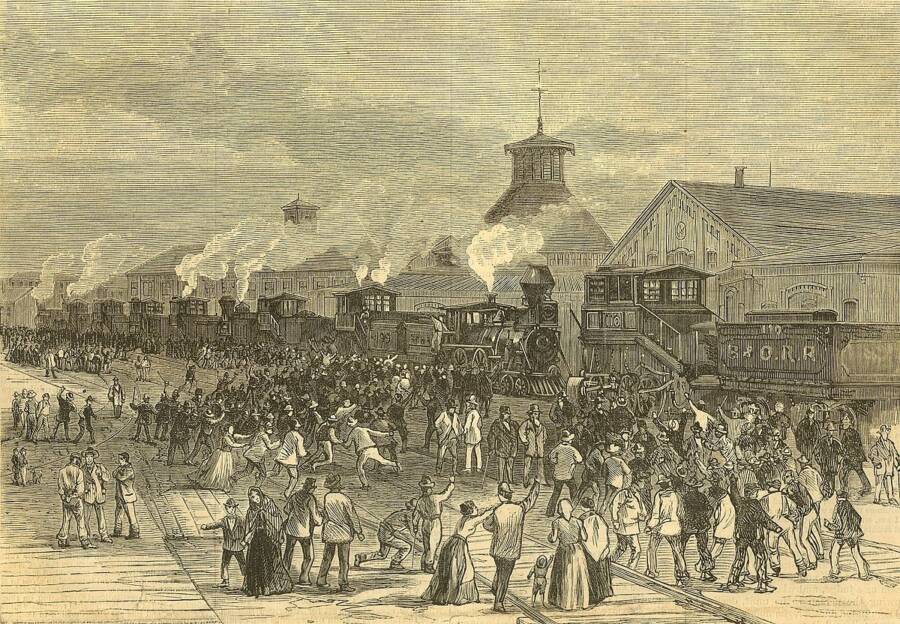

Wikimedia CommonsThe Great Railroad Strike of 1877 began in West Virginia and Maryland and quickly spread across the country.

By 1877, American railroad workers had long been fed up with their low wages and poor working conditions. An announcement of yet another pay cut for workers at the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad in July of that year sparked a massive strike that stretched across multiple states.

At its height, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 boasted the support of more than 100,000 workers across West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Missouri, and Illinois. The first multi-state strike in U.S. history, the protest wasn’t organized by any one large national group. Instead, it was spontaneously planned by the employees themselves.

Railroad companies and the government immediately acted to suppress the strikes, sending militias and soldiers to stop the workers from revolting. By August, the strike had largely ended, with 1,000 arrests and 100 deaths.

While the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 resulted in more official efforts to organize future trade unions and the labor rights movement, there were no immediate major victories for railroad workers, even though the protest had briefly sparked rumors of a “second American Revolution.”

How An Economic Depression Paved The Way For The Great Railroad Strike Of 1877

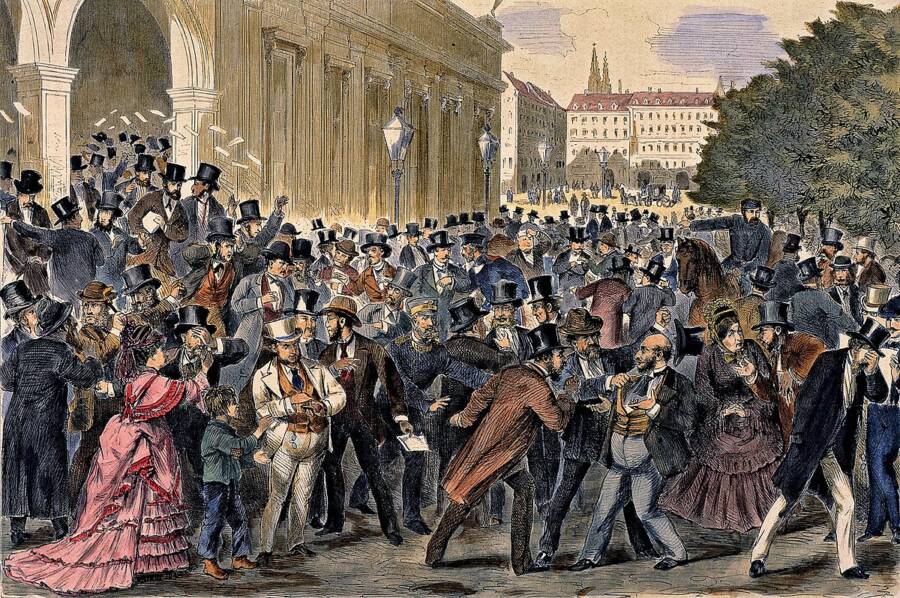

Wikimedia CommonsThe Panic of 1873 impacted North America and Europe, and led to the longest economic contraction in U.S. history.

Sparked by a financial crisis called the Panic of 1873, the longest economic contraction in U.S. history began, ultimately lasting 65 months. This was even longer than the contraction that occurred during the Great Depression.

Unemployment rose to 14 percent by 1876, and wages dropped significantly for many working-class people in America. Many businesses were forced to shut their doors, and the national construction of railways decreased from 7,500 miles of track in 1872 to just 1,600 miles in 1875.

The economy was in a rough place, and railroad companies were struggling to keep up. During the “Long Depression,” the companies were trying to find ways to cut costs. They found their answer in their workers’ paychecks.

Beginning in 1874, the railroad company Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad cut their workers’ pay to almost half of their pre-Long Depression wages over the course of three years. Workers were already getting frustrated with all the pay cuts when the president of the company announced an additional 10 percent pay cut in July 1877.

The president of the company claimed the effects of the Panic of 1873 were still “seriously affecting the usual earnings of railway companies” and they needed to cut pay in order to keep investors happy.

This was obviously not what workers wanted to hear.

Not long after the announcement was released, workers in Maryland and West Virginia began planning what would become the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, soon inspiring people in other states to join their cause.

America’s First Multi-State Worker Uprising

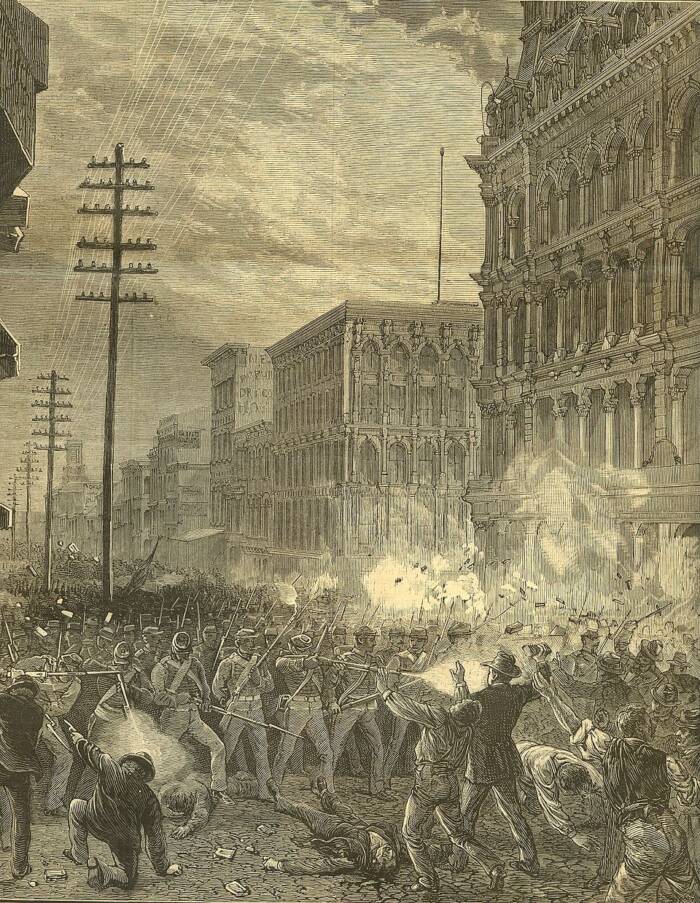

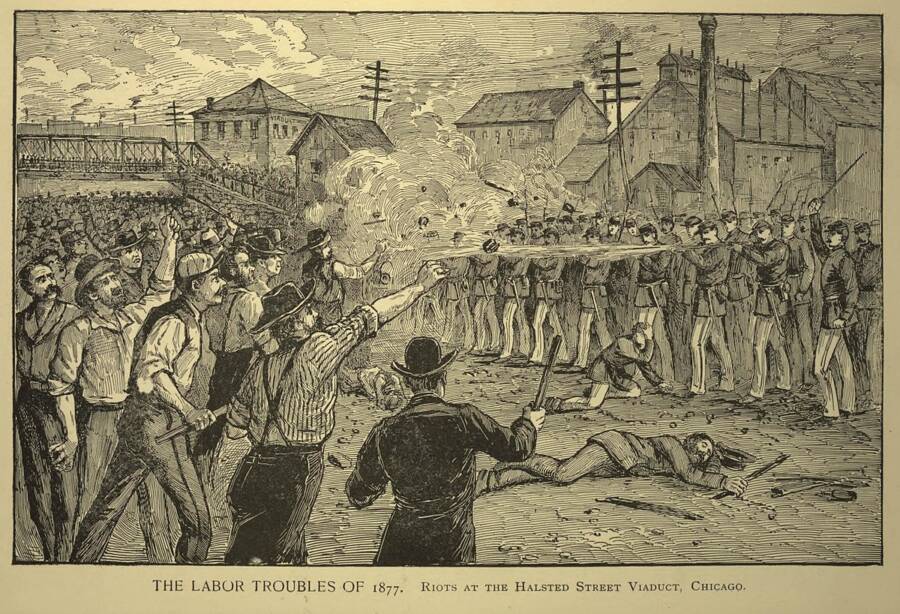

Wikimedia CommonsTroops opened fire on the strikers in Baltimore, Maryland, killing 11 people.

The earliest strikes began in Baltimore, Maryland and Martinsburg, West Virginia by mid-July in 1877. The striking workers were often joined by some other community members who wanted to support the railroad workers. In some cases, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 crossed divisions of race and gender, as white, Black, and immigrant workers all participated, and women and children sometimes appeared to cheer on the cause.

In Martinsburg, striking workers at the B&O station confined the locomotives in a roundhouse and refused to allow any trains to leave until the pay cut was rescinded. West Virginia Gov. Henry M. Mathews called in local militia forces to help get the trains moving once again. But the militia failed.

The governor requested assistance from the federal government, and in response, President Rutherford B. Hayes sent federal troops to the city. The unrest led to the death of a striker, who had exchanged fire with a soldier. But the demonstration in Martinsburg was only the beginning.

The strike was also heating up in Baltimore, where many trains were completely stopped by striking workers. Frustrated, Maryland Gov. John Lee Carroll called in the Fifth and Sixth Regiments of the Maryland National Guard in Baltimore for assistance by July 20th.

In response, strikers threw stones and pieces of iron at the troops. The soldiers eventually fired directly into the crowd, killing 11 people. Further violence ensued as the protesters then burned trains and nearby buildings.

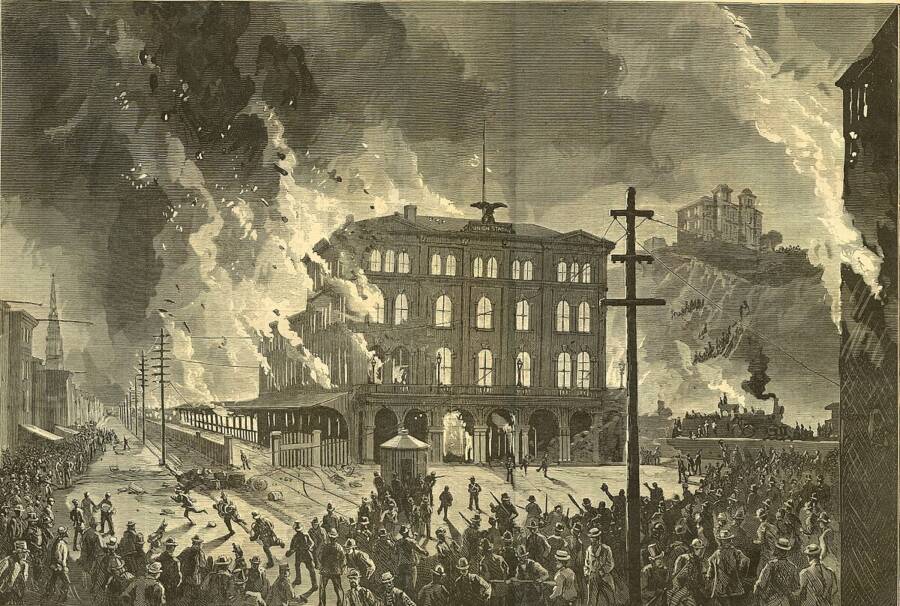

Wikimedia CommonsProtesters burned down the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Union Depot in Pittsburgh during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

They also passed out manifestos that read, “Be it understood, if the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company does not meet the demands of its employees at an early date, the officials will hazard their lives and endanger their property, for we shall run their trains, and locomotives into the river; we shall blow up their bridges; we shall tear up their railroads; we shall consume their shops with fire and ravage their hotels with desperation.”

The strike continued to spread. In Pennsylvania, protests popped up in a number of cities, including Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Reading, and Scranton.

In Pittsburgh, local police and militia troops refused to intervene in the protest, so Pennsylvania Gov. John Hartranft sent in the National Guard. What happened next would be one of the most violent clashes between strikers and law enforcement during the Great Strike of 1877.

Upon arriving in the city, National Guard troops were immediately mocked and taunted by protesters. The troops eventually began to open fire on the crowd, not unlike the scene that unfolded in Baltimore.

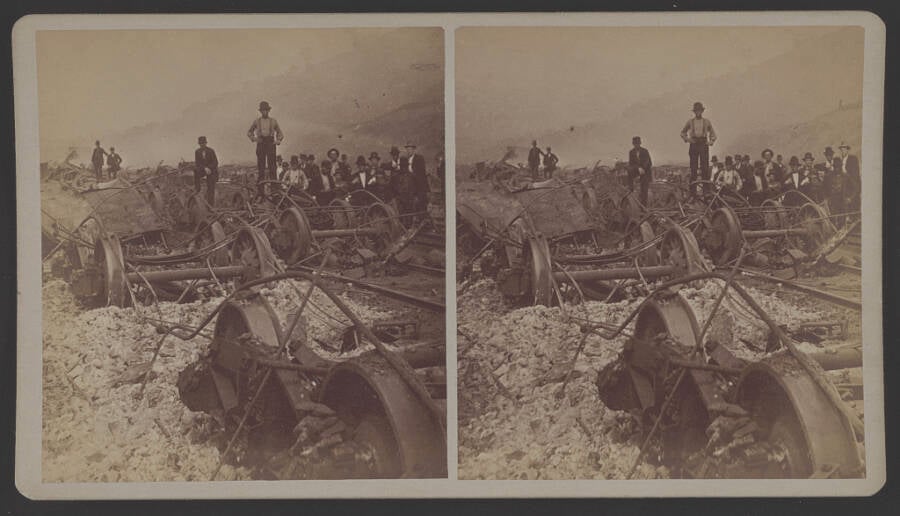

This time, the troops killed 20 people, including three children. Following the attack, protesters burned down or damaged numerous buildings, locomotives, passenger cars, and freight cars in the city. The Pennsylvania Railroad would later claim losses of over $4 million in Pittsburgh alone.

The strike continued to spread throughout the country, with protests emerging in states like New York, Missouri, and Illinois. There was even a protest all the way across the country in San Francisco, California, which tragically ended as a racist riot against the local Chinese population.

Not Much Changed For Workers Immediately After The Great Railroad Strike Of 1877

Library of CongressA scene from the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 in Pittsburgh.

The strike began to lose steam as President Hayes continued to send federal troops to affected cities, as requested by governors and railroad companies.

Though Hayes understood why workers were frustrated, he showed little sympathy after the protests erupted into violence. In a proclamation he gave on July 18, 1877, he warned people against “aiding, countenancing, abetting or taking part in unlawful proceedings,” and ordered them to “retire peaceably to their respective abodes on or before” the next day.

Still, over 100,000 workers participated in the strike across the country. It was a remarkable feat, especially considering how organic the protest was.

The strike briefly brought America’s major railroads to a halt and helped energize and organize the working class like never before, with some cities even seeing a general strike. But despite the uproar and protests, workers did not see immediate wage or working condition improvements.

By August 1877, the protest was essentially over, with no major wins for the striking workers. Furthermore, an estimated 1,000 people had been arrested and approximately 100 people had died, many of whom were the strikers.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Great Railroad Strike of 1877 quickly spread throughout the country, but it was nearly forgotten by history.

However, the strike also brought the issue of labor rights to the forefront of public attention. Unions also became more common and more organized.

In 1880, B&O introduced the Baltimore and Ohio Employees Relief Association to provide some benefits to employees and their families in case of injury, sickness, or death. By 1884, there was also a pension plan.

Though the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 remains lesser known today than other strikes, like the Pullman Strike, which led to Labor Day, there were other long-term impacts of the 1877 protest that can still be seen today.

It led to increased support for the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which limited the president’s ability to deploy U.S. federal troops to participate in civilian law enforcement. In addition, some unexpected physical reminders of the 1877 strikes are the many armories built throughout the U.S. for the National Guard in the event of future social unrest.

While some of those armories have been repurposed as museums or event venues, they are an ever-present reminder of the first multi-state worker uprising in the U.S. — and the “second American Revolution” that wasn’t.

Next, read about the Molly Maguires, the secret society that fought bloody battles for workers’ rights in 1870s Pennsylvania. Then, discover tragic photos of child miners that expose the ugly history of American coal.