When Charles Millar died childless in 1926, he bequeathed his fortune to whichever woman could bear the most children in a 10-year span. What followed was a baby boom the likes of which Canada had never seen.

Toronto Star Archives/Toronto Star via Getty ImagesMrs. Arthur Hollis Timleck claimed to have given birth to nine children in a ten-year period in a bid to win Charles Millar’s fortune.

On the night of Halloween 1926, a wealthy Canadian lawyer, financier, and now-legendary jokester died.

Relatively unknown until his death, it would be the last will and testament of Charles Vance Millar that propelled his name into infamy. An unusual clause in his will promised the bulk of his gargantuan estate to the woman who could birth the most babies in Toronto over the decade following his death.

What followed was an unprecedented baby boom now called the Great Stork Derby of Toronto.

Charles Vance Millar, An Eccentric Multi-Millionaire

Charles Vance Millar was born on June 28, 1854, in Aylmer, Ontario. He became a prominent lawyer and worked out of his downtown, Toronto-based firm.

Wikimedia CommonsCharles Vance Millar’s portrait taken by an unknown photographer sometime before 1926.

He was a notorious jokester and delighted in playing with people’s love of money. Millar would drop dollar bills on the sidewalk and hide in the bushes to watch people’s faces as they quickly stuffed the money into their pockets when they thought no one was looking.

He also told his friends that this pastime “was an education in human nature by itself.”

In 1926, after a successful career as a lawyer, racing stable owner, and president of a brewery, he died suddenly at his desk while in a meeting with a few associates. He was 73 and a bachelor with no immediate family to inherit his estate.

The facetious millionaire’s last will and testament were dripping in irony. For one thing, he left his stock in a brewery and an entire race track to a group of prohibitionist Protestant ministers and $500 to a housekeeper who was already dead.

He even bequeathed a holiday estate in Jamaica to three lawyers that hated each other on the condition that they all live there together.

Millar admitted that his will was “necessarily uncommon and capricious” and chastised himself for amassing more wealth than he could spend in his lifetime.

“What I do leave,” Millar wrote, “is proof of my folly in gathering and retaining more than I required in my lifetime.”

But the most notable clause of the eccentric will would go on to transform the lives of all Toronto families, causing a decade-long media frenzy, and perversely give endless trouble to the very legal system that Millar had once been a part of.

The bulk of Millar’s estate, the millionaire wrote, would be given “to the mother who has since my death given birth in Toronto to the greatest number of children.”

And So, The Great Toronto Stork Derby Begins

Toronto Star Archives/Toronto Star via Getty ImagesMrs. Darrigo claimed to have had nine children since Oct. 31; 1926. This would have placed her among the leading entries in the derby.

Millar’s will stipulated specifically that 10 years after his death, his fortune — which turned out to equate to more than $10 million by today’s standards — would be given to the Toronto mother who had given birth to the most children according to the Canadian birth database. If there was a tie, the money would be divided among the mothers.

Some believed the stunt was all a prank to amuse Millar’s friends and to test the legal system. Others thought that it was a statement in support of contraception by “turning the spotlight on unbridled breeding” meant to “shame the government into legalizing birth control.”

Whatever Millar’s true motivation, it became an elaborate and much-watched social, mathematical, and biological experiment.

What ensued was a baby-making race, a so-called Baby or Stork Derby.

At first, the media called Millar’s now-public will a “freak” document. Nobody could believe it. But soon, newspapers around the country began to follow the story. The Toronto Daily Star even assigned a special reporter to the “great stork derby” who was responsible for chasing pregnant women around the city for exclusivity agreements.

Soon, all of Canada (and the neighboring United States) was watching. Countless mothers with growing broods began to claim their place as contenders.

The Fruitful Contenders

Toronto Star Archives/Toronto Star via Getty ImagesThese were the leading contenders in the stork derby meet each other over a meal for the first time.

When Millar died, he had no idea that his investments would pay off so well. He also had no idea that the Great Depression would hit in the thirties, making his estate a shining beacon of hope to overcrowded families fighting to survive.

As the years went by, 11 families officially competed in the Great Stork Derby.

The media went nuts in the days leading up to the 10-year deadline. New contenders were introduced until the very end and the world watched in suspense.

On Oct. 31, 1936, at 4:30 pm, exactly 10 years after Millar’s death, the contest was closed.

Some women tried to claim births that weren’t officially registered, as well as babies fathered by men that weren’t their husbands. Other questions arose: did stillbirths count? What about children born to unmarried mothers? Did those living in the area around Toronto qualify?

Don Dutton/Toronto Star via Getty ImagesMrs. Larry Sheppard was also on a bid for the fortune, pictured here with 10 of her 12 children.

In the end, Judge William Edward Middleton, a man sympathetic to large families being himself the eldest of nine, made the final decision on a winner.

He declared a tie between Annie Katherine Smith, Kathleen Ellen Nagle, Lucy Alice Timleck, and Isabel Mary Maclean, each of who gave birth to nine children during the qualifying decade.

Timleck, Nagle, Smith, and MacLean all got about $125,000 each, which is around $2 million by today’s standards. Kenny and Clarke received smaller amounts as their stillborn, illegitimate, or unregistered children were not counted in their totals.

This amount was enough for the mothers to buy new houses and to pay for their children’s educations.

Legislative Aftermath

Toronto Star Archives/Toronto Star via Getty ImagesMr. and Mrs. Arthur Timleck were a part of the four-way tie for Millar’s fortune, after which they took a trip to New York to celebrate.

As a lawyer himself, Millar made sure to write the “stork derby” clause of his will so that it would withstand court challenges. But from the day his will was announced, it was nonetheless challenged from all directions.

Over the course of the 10 years following his death, it bounced from court to court.

Some accused the scheme of being against public policy. The Globe wrote that it was “encouraging the birth of children with no regard to their chances of life or welfare.”

Distant relatives of Millar suddenly materialized and tried to get their hands on his fortune, which they never did.

Meanwhile, the province of Ontario tried to redirect the money to the government.

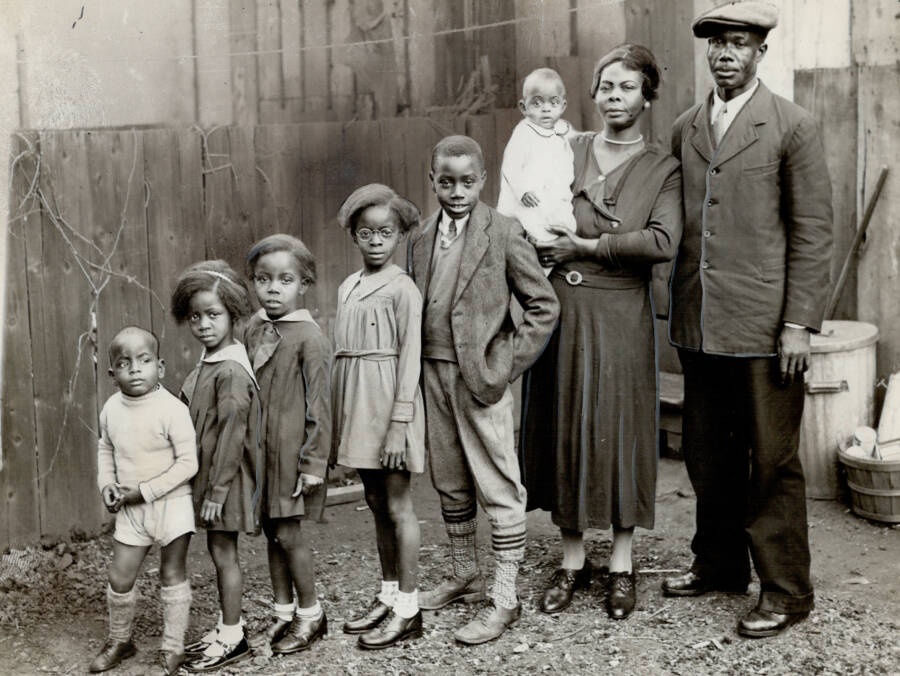

Toronto Star Archives/Toronto Star via Getty ImagesHere’s John William Carter; a 50-year-old West Indian father of the first family of color to enter the stork derby.

Ultimately, the case made it through the Supreme Court of Canada and the clause was declared valid.

On May 31, 1938, the Ottawa Citizen reported that at long last, the great stork derby “sensation” had concluded and this “strange chapter in legal and obstetrical history” brought to a close.

After this, read up on another eccentric aristocrat, Sarah Winchester, of the Winchester Mystery House. Then, check out the story of Hetty Green, one of America’s most wealthy — and stingy —citizens.