At one of the darkest points of the Cultural Revolution, political strife devolved into extreme brutality in China’s southern region of Guangxi, where hundreds were cannibalized.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesDuring China’s Cultural Revolution, petty political rivalries turned brutal during the Guangxi massacre when civilians began murdering and cannibalizing their opposers.

Modern Wuxuan County, in southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, is a relatively quiet corner of the country, marked by wide green farm fields and bustling small towns.

Nothing about the area would suggest that in the late 1960s, at the height of the country’s Cultural Revolution under Mao Zedong, local Red Guards and Communist officials subjected their rivals to horrific levels of humiliation and violence.

But the extent to this terror would have gone unknown if not for the reporting of a Chinese writer in the early 1990s, who uncovered unparalleled levels of savagery, depravity, and even cannibalism in what has since become known as the Guangxi massacre.

Mao’s Cultural Revolution Causes Chaos

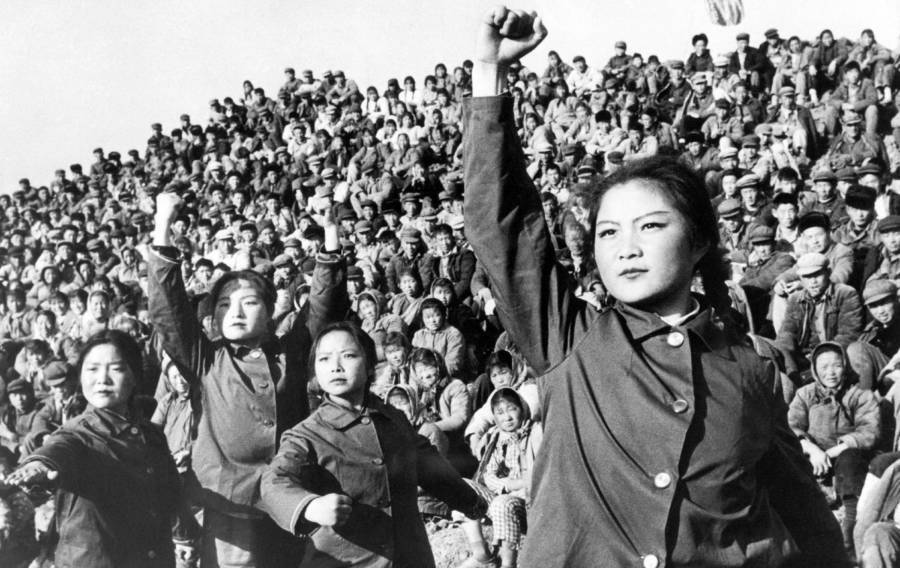

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty ImagesPeople of all ages and backgrounds were expected to take part in the Cultural Revolution, with young people encouraged to join the violent Red Guards.

In 1958, Chinese premier Mao Zedong launched the Great Leap Forward, an ill thought-out campaign to transform the country into an industrial powerhouse. The results were disastrous: over 50 million people died during the ensuing Great Chinese Famine, and tens of thousands more in a series of related disasters.

Mao was thus forced to admit his failure in 1962 and step down from the presidency, but he retained leadership of the Communist Party. The humiliated leader refused to accept even a minor demotion, however, and soon began planning his path back to supremacy.

He did so on May 16, 1966, when he publicly accused several high-ranking leaders of being “counter-revolutionary revisionists” plotting to undermine his Party from within.

Soon after, Mao gave his blessing to the Red Guards, a group of militant, idealistic students who revered him and violently opposed anyone suspected of disloyalty and who ousted any dissenters.

As local governments broke down under constant attacks from Red Guards and factional infighting, ordinary citizens lost faith in national politics and turned on each other in the frenzy.

In such a charged atmosphere, ordinary citizens saw each other as class enemies to be destroyed. What ensued was a civilian clash that saw lynching, torture, and violence spread across the region.

Citizens Cannibalize Their Political Opponents

Bettmann/Getty ImagesMao indicated “Five Black Categories” for his rivals, which included rightists, counter-revolutionaries, “bad influences,” wealthy farmers, and landlords.

All over the country, violent uprisings occurred. So-called “Struggle Sessions” became a popular form of punishment during which members of the Chinese Communist Party publicly humiliated and tortured dissenters or opponents.

But these sessions often turned extremely violent, and in some regions, devolved to cannibalism.

While cannibalism had occurred in China during the Great Famine out of desperation or necessity, by the late 1960s, food supplies had been largely restored. Therefore, the mass demonstrations of cannibalism in Guangxi couldn’t have been due to hunger.

The real cause was political hatred. According to one eyewitness, “All the cannibalism was due to class struggle being whipped up, and was used to express a kind of hatred. The murder was ghastly, worse than beasts.”

Some of the worst such demonstrations took place in Wuxuan County, where officials invoked a grisly tradition of eating their rivals’ hearts, livers and genitals.

That horrific practice began in 1968 when students at Wuxuan Middle School beat their geography teacher to death and carried her body to the banks of the Qian River where they forced another teacher to cut out her heart and liver.

Back at the school, the students cooked and ate the organs.

Senior officials also reportedly took part in “flesh banquets,” reserving the tender hearts and livers of their opponents in Struggle Sessions for themselves to boil with spices and pork. Lower-ranking citizens “were allowed only to peck at the victims’ arms and thighs.”

One Communist Party member, named Wang Wenliu, developed a reputation for eating male genitals or preserving them in liquor. After she was promoted, Beijing learned of her bloody habit and demanded to know why she hadn’t been ejected from the Party.

A subsequent investigation found that she had, in fact, only eaten flesh and liver. She was demoted, but allowed to keep a job in the Party.

Then in May 1968, a particularly violent uprising in the Communist Party saw one chairman mobbed and dismembered, with his head and a leg bone hung in a public square. Red Guard militants then spotted his brother, beat him severely, and pushed him into a sewer pit where they cut out his heart and liver while he was still alive.

Others quickly stripped his body of flesh, and his bones were dumped in the river.

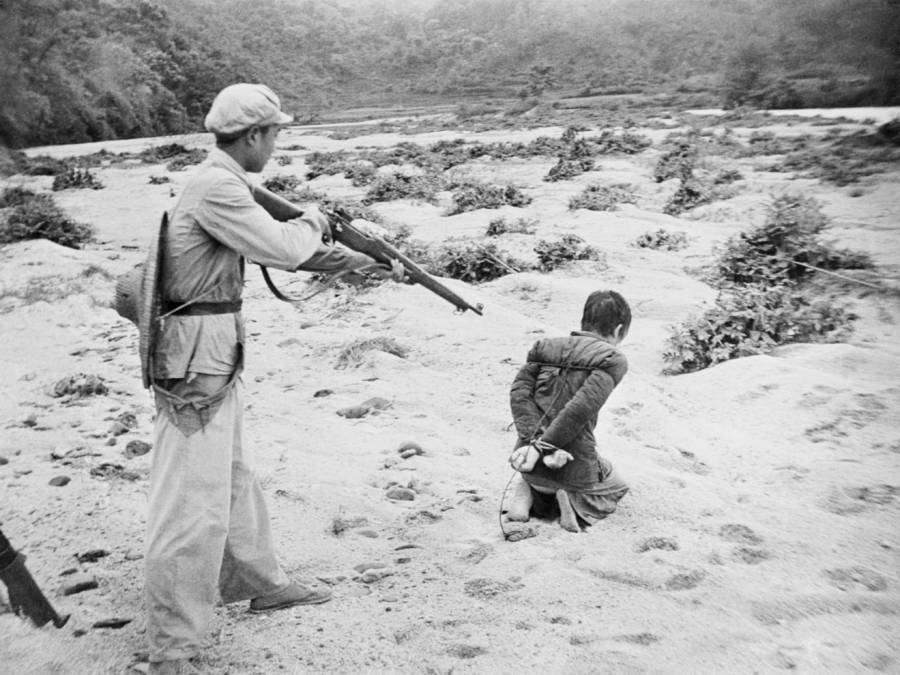

Sovfoto/UIG via Getty ImagesA former landlord is publicly humiliated during a “struggle session,” a form of torture designed to shame the victim and heighten their accusers’ anger.

For nearly a decade, the citizens of Guangxi were plagued by “beheadings, beatings, live burials, stonings, drownings, boilings, group slaughters, disembowellings, digging out hearts, livers, genitals, slicing off flesh, blowing up with dynamite, and more, with no method unused.”

The official number of people consumed throughout the region is 137, but the real death toll is likely hundreds more.

Of those documented, at least 38 incidents of cannibalism took place in Wuxuan County. As one participant in the Guangxi massacre later proudly claimed, “In Wuxuan … we ate more people than anywhere else in China.”

An End To The Violence

Bettmann/Getty ImagesWith the end of the Cultural Revolution, mass rallies, Struggle Sessions, and politicized warfare like that seen in Guangxi disappeared as China struggled to recover.

The most violent stage of the Cultural Revolution ended in late 1968, when Mao ordered that thousands of Red Guards be “sent down” to labor in the countryside. On Sept. 9, 1976, Mao died, and with him the Cultural Revolution.

But instances of lynching and political violence continued as the Guangxi massacre dragged on. A period of purging in a campaign that sought to “eliminate chaos and return to normal” was launched.

A handful of those deemed responsible for the violence in Guangxi were sentenced to prison terms, dozens were expelled from the Party, and dozens more were demoted or received a pay cut. After that, Beijing’s official stance was to forget and deny that cannibalism had ever taken place in Guangxi, or at least that they’d known of.

Yet the central government had been aware of the Wang Wenliu case, and researchers 20 years later discovered at least one message had been sent to the capital regarding the tragedy, which read simply: “People are eating each other.”

People’s Pictorial/Wikimedia CommonsJiang Qing, top left, Mao’s last wife, meets Red Guards at a rally in 1966. After her husband’s death 10 years later, she and three other prominent leaders were blamed for the worst excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

The horrifying events of the Guangxi massacre might have been forgotten had not the essayist Zheng Yi traveled to Guangxi in 1986 to investigate the 20-year-old rumors of cannibalism.

A former Red Guard who’d spent time in Guangxi during the Cultural Revolution, Yi successfully overcame the official silence which pervaded the massacre. He gained access to official records which proved that local and national authorities were aware of the savageries during and after they took place.

Fearing for his safety, Yi only began writing his exposé after being arrested for participating in the Tiananmen Square Protests in 1989. Hiding out for two years, he completed a book detailing the violence in Guangxi, published it under a pseudonym, and fled to the United States via Hong Kong.

Dotted all over China are countless monuments to the victims and martyrs of the Chinese Civil War, the Japanese invasion, and other tragic and bloody periods. Yet the Communist Party has never admitted to what happened in Guangxi in 1968 for fear of destabilizing their regime and undermining their authority.

As such, the survivors of Wuxuan have never received official recognition for the terror they endured.

After learning about the tragic horrors of the Guangxi massacre, take a closer look at life during the Cultural Revolution in shocking images. Then, find out about Trofim Lysenko, the Soviet pseudoscientist whose bizarre ideas fueled China’s Great Famine.